Tom Brokaw is worried that Washington is out of touch. People feel politics “is a closed game that doesn’t address what their real concerns are,” he told Howard Kurtz of the Daily Beast. “It has its own language, it has its own culture.”

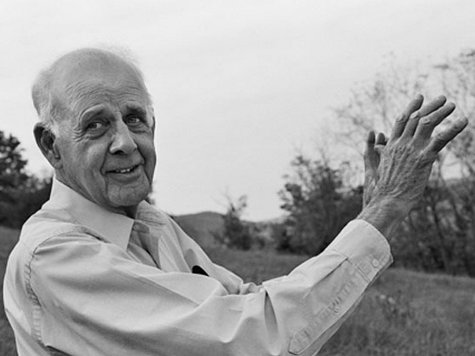

Right thought, wrong target. The broadcaster was referring to the White House Correspondents’ Association dinner held on April 28. A more telling and troubling example of this disconnect occurred earlier that week, when author Wendell E. Berry gave the 41st annual Jefferson Lecture for the Humanities.

The April 23 speech, which you paid for through the National Endowment for the Humanities, showcased the Washington mindset at its most myopic and misguided.

“Under the rule of industrial economics,” said Berry, “the land, our country, has been pillaged for the enrichment supposedly of those humans who have claimed the right to own and exploit it without limit.”

“Of the land community,” he continued, “much has been consumed, much has been wasted, almost nothing has flourished.”

This will come as news to the American farmers and scientists who pioneered high-yield agriculture, which has benefited humanity across the globe. In 1960, one U.S. farmer fed about 26 people worldwide; now it’s about 155, according to the Center for Food Integrity. It’s called the Green Revolution, named before environmentalists claimed exclusive rights to the term.

But no matter. In his address, Berry admitted he had little use for “data, or facts, or information.” “We humans are not much to be trusted with what I’m calling statistical knowledge,” he said. “We don’t learn much from big numbers.”

Berry is a beloved fixture in the Washington culture. A Kentucky farmer and social critic who once spoke out against the Vietnam War, he now supports environmental causes, such as the banning of mountaintop mining. Like many Washington elites, Berry represents a strain of progressive politics that despises the trappings of progress.

“The economic hardship of my family and of many others a century ago was caused by a monopoly,” Berry argued, telling the story of his grandfather, a tenant farmer constantly in debt.

Berry blamed his grandfather’s plight on James B. Duke, the tobacco baron and patron of Duke University. But his sights were set squarely on the American system. “Disregarding any other consideration,” Berry said, Duke “followed a capitalist logic to absolute control of his industry and incidentally of the economic fate of thousands of families, such as my own.”

Never mind that monopolies are by definition not capitalistic. And never mind that capitalism paid for the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts, where Berry spoke, and everything else of value in Washington. In Berry’s passion play, capitalism is the villain, symbolized by a “large machine in a large, toxic, eroded cornfield.”

The imagery will be familiar to anyone who has read John Steinbeck’s novel The Grapes of Wrath, which portrayed soulless tractors displacing family farmers during the Dust Bowl. What Steinbeck and Berry’s grandfather could not foresee, and what Berry chooses not to see, is that mechanization and technology would produce an agricultural bounty that would save hundreds of millions of lives in the developing world.

In fact, American farms yielded 153 bushels of corn per acre in 2010, compared to 24 bushels in 1931, according to the Corn Farmers Coalition, which predicts the number could rise to 300 bushels by 2030.

But such “big numbers” cannot penetrate Berry’s zero-sum worldwide. In his speech, Berry borrowed from historian and novelist Wallace Stegner in dividing the nation into two classes: “boomers” and “stickers.”

The stickers “are motivated by affection, by such love for a place and its life that they want to preserve it and remain in it,” Berry said, adding, incredibly, that “the promise of a stable, democratic society [is] not to be found in mobility.” (Don’t you dare think of moving to where the jobs are!)

The boomer, on the other hand, “is motivated by greed, the desire for money, property, and therefore power,” Berry said. “By thoughtless consumption of goods ignorantly purchased, now we all are boomers.”

Such self-flagellation is catnip to the Washington culture. Berry “has a way of talking to city people that allows us to empathize with the farm life,” wrote Mark Bittman of the New York Times.

This head-patting paternalism, as practiced by Washington pooh-bahs, inevitably leads to unintended consequences.

Item: The Delhi Sands flower-loving fly was listed as an endangered species just before ground was to be broken on a new hospital to serve California’s San Bernardino and Riverside counties. Construction was delayed for over a year, according to the National Center for Policy Analysis.

Item: Another endangered species, the Kangaroo rat, was cited by regulators in prohibiting homeowners in rural southern California from clearing overgrowth from their yards. Soon thereafter, a wildfire fueled by the brush destroyed the homes — and, presumably, the rats’ habitats.

Item: A federal regulation requiring oxygenates such as methyl tertiary butyl ether [MTBE] to be added to gasoline to protect the environment actually polluted groundwater to such an extent that it will cost billions of dollars to clean it up.

It is difficult to square these epic failures with Berry’s concern for the “stickers.” In some ways, things are worse now than in Berry’s grandfather’s time. Back then, Washington led the effort to bring electricity and indoor plumbing to rural communities. Today, Congress bans incandescent light bulbs and high-flush toilets.

Berry’s amber-stuck intellect can only see one way forward — the way of Washington. He advocates a “50-Year Farm Bill” that should raise eyebrows among those who remember the Soviet Union’s disastrous five-year plans.

He also preaches “sustainability,” the new code word for economic decisions made by central planners living far from where the effects will be felt. Some “stickers,” like unemployed coal miners and oil workers, are feeling the effects already.

Wendell Berry’s America would, to borrow his language, follow a collectivist logic to its absolute end, an economic nightmare more often seen in the nations to which we donate food. It is worse than ignorant; it is willfully blind.

His speech is a useful reminder of Washington’s eagerness to bite the hand that feeds and comforts and powers the world. It earned thunderous applause from the audience by the Potomac. But it should give pause to the rest of us.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.