I thought Crash was the worst movie Hollywood could make that bamboozled critics and audiences into thinking it was something “important,” never mind “entertaining,” and “Best Picture” worthy.

Now comes Prisoners, a relentlessly grim, ponderous tutorial in amateur character and plot construction that is too clever by half, champions nihilism, mocks faith and is ultimately an unredeemable exercise in despair.

******* SPOILERS AHEAD *******

A great movie takes a character and sends him, at least, on a journey of transformation. He is given an existential goal, and in order to accomplish it, he must tackle and transcend his internal conflicts and fatal character flaws in order to defeat his opposition and claim the prize. Along the way, he transforms, usually into a better version of himself.

Movies don’t have to have happy endings. Characters can start as good and righteous people and, in a cautionary tale, discover terrible things about themselves while achieving some goal. David Lynch’s Blue Velvet is a great example.

Kidnapping stories can provide intriguing moral quandaries for such characters, as they must weigh their own morality against what must be done to retrieve a loved one. Such is the ostensible conflict in Prisoners, yet it is so clumsily handled and ultimately leads to nothing, that we are left to wonder why any of our characters were subjected to their ordeals.

Faith vs. Despair

Is there anything more stupid and lazy, especially in the post-Incredibles era, when a villain explains their modus operandi, and how they carried out their evil plan, in a clunky monologue to the hero (and us)?

I give you Prisoners’ kidnapper/killer, Holly Jones (Melissa Leo). She and her dead husband kidnapped children in order to drive the parents to despair and “turn them into demons.” They did this to spite God when their only child died of cancer. This motivation is revealed by Jones in a ham-handed monologue, as she explains herself to the drugged Dover as she prepares to kill him.

I can’t believe it! He got her monologuing!

Too bad, because it’s a theologically sound idea and makes for interesting motivation. As Christians know, and as stories like The Exorcist dramatize, Satan loves to create despair and ultimately drive people to suicide.

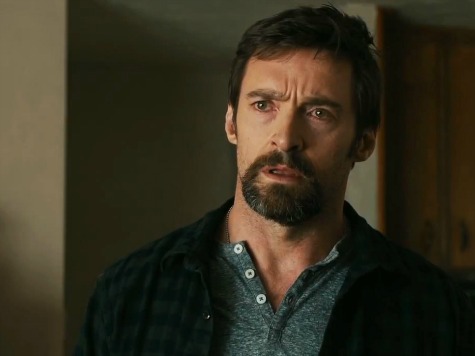

However, for the story to make sense, Keller Dover (Hugh Jackman) should have either started as a man of faith but not succumb to despair despite having every reason to as he searches for his kid, or started as a man of faith and succumbed to despair in the end. There may even be a route in which he begins as a man in despair and finds faith through his harrowing journey.

But instead, we get typical Hollywood wishy-washy indecisiveness regarding the character. We see Dover pray a couple of times, but otherwise there are no demonstrations of faith whatsoever (you can hear the studio notes: “Don’t make him a religious fanatic!”). In fact, he appears to be more of a survivalist than devout Christian. Or Catholic. Or…well…we don’t even know his exact faith.

In the end, he appears to maintain his faith after being left for dead in Jones’ pit because we see him pray. However, in the interim, he brutally tortures the so-mentally-challenged-he-can’t-answer-simple-questions-but-not-so-mentally-challenged-he-can’t-drive-an-RV Alex Jones (Paul Dano) to the brink of death, convinced Jones knows where his kid is. Not only that, Alex Jones does not provide a single clue–NOTHING–that helps Dover solve the case.

So in that regard, Holly Jones succeeds in turning Dover into a demon. She wins. And even worse, if Dover is found alive, he’ll go to prison for torturing Alex, so when Loki hears the whistle at the end, we’re supposed to be relieved? Happy?

What emotion did the filmmakers want us to feel at the conclusion, other than being glad that 140 minutes of our own torture was now over? Was this supposed to be a film about faith? About what one must do to survive? About moral choices? What is Detective Loki’s character transformation? Why did he need to take this journey? How does he change as a result of this ordeal? He doesn’t!

Why did the filmmakers take us on this grim, hopeless, despairing journey? As the audience, we’re meant to think, “Oh, how daring! They made this guy go the edge to find his daughter and it turns out to be for nothing!” What possible value does this nihilist stance provide the audience? What is the point of this entire exercise?

So while I can praise all the actors for great work in every respect, and the technical proficiency of the filmmaking, I otherwise find no redeeming value in the movie in any respect. And I haven’t felt that way about a film since the even more execrable Killer Joe.

Plot Holes

We are meant to believe that Jones’ husband goes to a Priest to confess the murder of 16 kids, and then that the Priest ties him up in his basement and leaves him to die, rather than report it to authorities? Why? We are given no explanation, even though dropping Holly Jones into a pit would have been poetic justice instead of her going down shooting.

The entire Bob Taylor subplot is a red herring with no payoff. Holly’s dead husband wore a maze necklace. Bob Taylor was kidnapped by Jones but escaped, and now spends his life replaying child kidnappings and murders, while drawing mazes all over his house. He steals the clothes of kids that actually do get kidnapped because….why? He puts snakes in containers with bloody clothes because…why?

Why make Dover a survivalist? It has no bearing whatsoever on any part of his character, or the story, other than the possibility that he is able to survive in the pit. Or was it that his faith helped him because he had no actual survival gear? I have no idea.

There is no purpose to the shooting of the deer at the start of the film. It’s not an immoral act. It has nothing to do with faith. There is no point to teaching his son about survival since the son is barely even in the movie, and survivalist instincts have no part in the film, either.

There are repeated shots of trees, where the position of a tree in frame or its relative degree of focus suggests that the trees are meant to be important, yet they have no payoff.

Why does Alex lift the dog by the neck and let it choke? It serves no other purpose than to make us think he may be involved, or may have killed the kids, and has no payoff.

Can this storytelling have been any sloppier?

Conclusion

Prisoners is worse than Hollywood putting lipstick on a pig–namely, taking a weak story, amping up the cleverness factor, throwing terrific actors in the mix, and adding an oh-so-ominous score (with cues at such equally ominous and obvious moments that I almost laughed).

This is Hollywood foisting its nihilistic values on audiences. At least with No Country for Old Men (which does not hold up on a second viewing), the nihilism at its core is offset because the film is about choices–that if you make choices that invite Death, he will pursue you until the end.

Prisoners appears designed to make audiences prisoners of despair. Stay away at all costs.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.