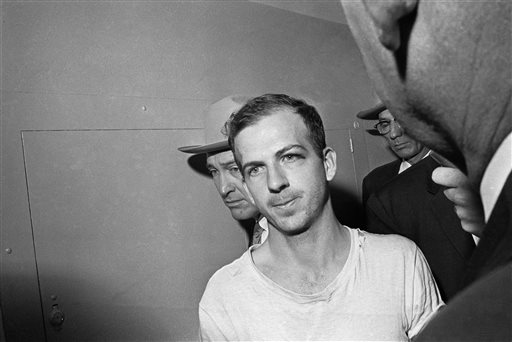

Last month, the Wall Street Journal published a fascinating essay by Peter Savodnik about Lee Harvey Oswald’s time in the Soviet Union. It reveals much about Oswald’s essentially introverted, tortured character, and provides a basis for understanding why the simplest explanation of the assassination of President John F. Kennedy forty years ago this week really may be the best: Oswald was a loner who acted alone.

Over and over again in his life, Oswald turned to the rigid discipline of an organized system to find a sense of belonging. First, he tried the Marines. Then, he tried the Communist Party. That culminated in his defection to the Soviet Union. However, Savodnik writes, the Soviets did not have much use for him. He had little useful intelligence to offer, and was no different from the “erratic and unstable” youth who embraced the USSR.

The only reason Oswald was able to stay was that he tried to kill himself when the Soviets ordered him to leave. That created a potential diplomatic incident. So the Soviets kept him on–but seemed more interested in spying on Oswald than in employing him as a spy. They gave him something of the life he wanted–an apartment in Minsk, a job, a wife, a community–and at the same time they watched him closely.

Oswald began to suspect that all was not what it seemed. “So, as he had done many times before, he fled,” Savodnik writes. “Each escape carried with it its own violence, and with each lurch the violence ratcheted up.” But Oswald was no apostate: for him, the loss of the Soviet Union as an ideal was not a political conversion but a personal failure. He sought to find a way to give meaning to his shattered life, and found it in Dallas.

In some ways–this is my analysis, not Savodnik’s–Oswald sought, through the death of one major figure, what many of today’s mass shooters seem to seek: a sense of notoriety, and through it, a definite (if perverse) place in society. He knew that he would lose his freedom, if not his life. But he also may have believed that he would have finally showed his worth to all those who doubted him, finally found a place in their Pantheon.

Regardless, what Savodnik’s research reveals is that Oswald was essentially a disturbed personality who sought refuge in radicalism and could not process being rejected by it, even as he rejected it in return. His terrible deed may not have been a Soviet (or Cuban) plot, but it was deeply entwined with his journey through communism, one that offered no way out for the radically alone but destruction, and self-destruction.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.