The end of the calendar year is typically the time that Presidents and other authorities grant pardons to convicted criminals or reinstatements to those deemed “ineligible.” More than ninety years after the most famous lifetime ban in history, it seems unlikely that Major League Baseball Commissioner Bud Selig will ever reinstate “Shoeless” Joe Jackson, one of the greatest hitters in the history of baseball.

In 1921 Major League Baseball’s first commissioner, Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis, banned the Chicago “Black Sox”–eight members of the 1919 Chicago White Sox who were involved with or had knowledge of a successful payoff scheme to throw that year’s World Series to the Cincinnati Reds–from organized baseball for life.

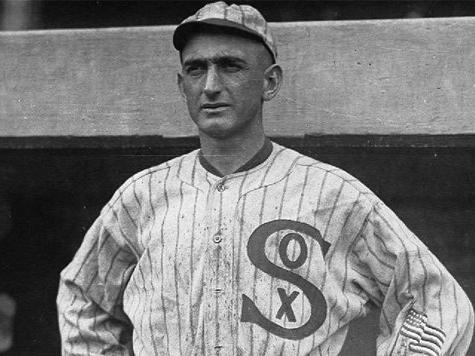

“Shoeless” Joe Jackson was one of those eight banned players. Over a fourteen year career with the Philadelphia Athletics, Cleveland Indians (then called the Naps) and the Chicago White Sox, he hit .356. Babe Ruth, the greatest player the game has ever seen, said of Shoeless Joe, “I copied Jackson’s style because I thought he was the greatest hitter I had ever seen, the greatest natural hitter I ever saw. He’s the guy who made me a hitter.”

In the 1919 World Series, which the White Sox lost 5 games to 3, Jackson committed no errors, and set a Series record for the most hits with 12. The record stood for 45 years until Yankee second baseman Bobby Richardson broke it with 13 hits in the 1964 World Series against the St. Louis Cardinals. Jackson also hit the only home run in the eight game series.

Jackson played all but the last three games of the 1920 season, but when news broke on September 26, 1920 that a Cook County grand jury had called him to testify about the fix, White Sox owner Charles Comiskey suspended him. Jackson never played another game in Major League Baseball.

The suspension held through the 1921 season. Despite the verdict of the Chicago jury, which on August 2, 1921 found all eight “Black Sox” players not guilty, Commissioner Landis, who had been granted unlimited powers by the owners of Major League Baseball, just one day later banned all eight for life from ever playing organized baseball again.

Supporters of Shoeless Joe, a South Carolina native who died there in 1951, have attempted unsuccessfully for decades to have him reinstated to the game. Many argue that it is a tragedy that one of the best hitters in the history of the game is not eligible for election to the Baseball Hall of Fame.

In 1999, South Carolina’s Congressional delegation, which included then Congressman (now Heritage Foundation President) Jim DeMint, then Congressman (now Senator) Lindsey Graham, Congressman Jim Clyburn, and Congressman Mark Sanford sent a letter to Commissioner Bud Selig in “strong support [of] the petition which has presented to your office regarding the reinstatement of ‘Shoeless’ Joe Jackson into Major League Baseball, clearing the way for his consideration into Cooperstown.”

Jackson’s supporters have maintained that he was a well meaning illiterate country boy who got caught up in the payoff scheme concocted by slick gamblers and his less than reputable teammates. They point to his stellar performance in the World Series that year as evidence that he did not participate in the fix.

While those arguments may well be true, there is strong legal evidence that he did take the money; $5,000 to be exact. That amount was delivered to him at his hotel room before the fifth game 1919 World Series by his teammate Lefty Williams. And if the transcript of his grand jury testimony given to Judge Charles McDonald on September 28, 1913 is to be believed, it is Jackson himself who confessed to taking the money.

From the transcript:

Q: Did anybody pay you any money to help throw that series in favor of Cincinnati?

A: They did.

Q: How much did they pay?

A: They promised me $20,000, and paid me $5,000.

Q: Who promised you the twenty thousand?

A: “Chick Gandil.

Q: Who is Chick Gandil?

A. He was their first baseman on the White Sox Club.

Q: Who paid you the $5,000?

A: Left Williams brought it in my room and threw it down.

Q: Who is Lefty Williams?

A: The pitcher on the White Sox Club.

Q: Where did he bring it, where is your room?

A: At that time I was staying at the Lexington Hotel, I believe it is.

Q. On 21st and Michigan?

A. 22nd and Michigan, yes.

Q: Who was in this room at the time?

A: Lefty and myself, I was in there, and he came in.

Q: Where was Mrs. Jackson?

A: Mrs. Jackson–let me see–I think she was in the bathroom. It was [a]suite; yes, she was in the bathroom, I am pretty sure.

Q: Does she know that you got $5,000 for helping throw these games?

A: She did that night, yes.

Clearly, Jackson was represented by legal counsel with a tremendous conflict of interest prior to his testimony. Whether Jackson was induced to make his self incriminating statement and how the purportedly private grand jury transcript quickly became public knowledge are mysteries that will never be answered.

The day after Jackson’s supposedly confidential grand jury testimony, headlines at several Chicago newspapers announced that he had confessed to taking money to throw the 1919 World Series.

At the time Jackson, who said he could not afford to pay for his own attorney, was represented by Alfred Austrian, who also happened to represent White Sox owner Charles Comiskey. In fact, Austrian’s legal fee was paid for by Comiskey. And the presiding judge of the Grand Jury, Charles McDonald, was a close personal friend of Comiskey, who was also well known for his close relationships with many prominent members of the Chicago press corps.

The grand jury transcript of Jackson’s confession mysteriously disappeared and was not entered into evidence in the 1921 trial in which he and the other “Black Sox” were acquitted. It suddenly reappeared in the 1923 civil trial in which he and teammate Buck Weaver sued White Sox owner Charles Comiskey for payment of their 1921 salaries while they were suspended. The jury decided in Buck Weaver and Jackson’s favor, but the judge overruled the jury’s decision when it came to Jackson.

The confession transcript disappeared for another 66 years until 1988 when the law firm that represented Comiskey in the 1922 trial made it public. In a cover letter to the Chicago Historical Society explaining how he came to be in possession of the grand jury transcript, attorney Frank Mayer of the law firm Mayer, Pratt, and Brown wrote:

Alfred S. Austrian of our firm . . was counsel to Charles A. Comiskey, the first owner of the Chicago American League team. In his office at 208 S. LaSalle Street on the morning of September 20, 1920, Austrian obtained Jackson’s confession (as well as that of his teammates Ed Cicotte and “Lefty” Williams) to having taken money from gamblers to throw the 1919 World Series to Cincinatti, the underdog. As is true today, an employer’s lawyer was not required by the rules of legal ethics to provide a Miranda-type warning to an employee suspected of dishonesty. Austrian then accompanied Jackson to the criminal courthouse, and the confession deteails were heard that afternoon by the Cook County Grand Jury…..

Alleging that Comiskey had wrongfully terminated their contracts, in 1923 civil suits were brought in Milwaukee by Jackson and other suspended “Black Sox” players against Comiskey. With the reasons for Grand Jury secrecy no longer existing, confession transcripts were provided for Austrian’s use through the cooperation of the Cook County State’s Attorney’s office. Based principally on the confessions, the judge held for Comiskey and overturned a jury verdict for the players.”

After he was banned from baseball in 1921 by Landis, Jackson never spoke of the incident again until 1949, when a young sportswriter, Furman Bisher, snagged the sports interview of a lifetime. In that interview, published in Sport Magazine “by Joe Jackson as told to Furman Bisher” that year, Bisher did not ask Jackson about his grand jury confession.

Jackson told Bisher he knew there was talk of a fix. “Sure I’d heard talk that there was something going on. I even had a fellow come to me one day and proposition me.” According to Jackson, “[i]t was on the 16th floor of a hotel and there were four other people there, two men and their wives. I told him: ‘Why you cheap so-and-so! Either me or you –one of us is going out that window.’ I started for him, but he ran out the door and I never saw him again. Those four people offered their testimony at my trial. “

Jackson also told Bisher he asked Comiskey not to play him in the 1919 Series. “When the talk got so bad just before the World Series with Cincinnati, I went to Mr. Charles Comiskey’s room the night before the Series started and asked him to keep me out of the line-up. Mr Comiskey was the owner of the White Sox. He refused, and I begged him: ‘Tell the newspapers you just suspended me for being drunk, or anything, but leave me out of the Series and then there can be no question.’ “

Jackson claimed that “I made 13 hits, but after all the trouble came out they took one away from me. Maurice Rath went over in the hole and knocked down a hot grounder, but he couldn’t make a throw on it. They scored it a hit then, but changed it later.”

As for the fix, Jackson said “I positively can’t say that I recall anything out of the way in the Series. I mean, anything that might have turned the tide. There was just one thing that doesn’t seem quite right, now that I think back over it. Cicotte seemed to let up on a pitch to Pat Duncan, and Pat hit it over my head. Ducan didn’t have enough power to hit the ball that far, particularly if Cicotte had been bearing down.”

According to Jackson, “I guess the biggest joke of all was that story that got out about “Say it ain’t so, Joe.” Charley Owens of the Chicago Daily News was responsible for that, but there wasn’t a bit of truth in it. It was supposed to have happened the day I was arrested in September of 1920, when I came out of the courtroom.”

As Jackson told it, “[t]here weren’t any words passed between anybody except me and a deputy sheriff. When I came out of the building this deputy asked me where I was going, and I told him to the Southside. He asked me for a ride and we got in the car together and left. There was a big crowd hanging around the front of the building, but nobody else said anything to me. It just didn’t happen, that’s all. Charley Owens just made up a good story and wrote it. Oh, I would have said it ain’t so, all right, just like I’m saying it now.”

Jackson recalled the outcome of his 1923 civil suit against White Sox owner Charles Comiskey differently than Comiskey’s former law firm. “I sued Mr. Comiskey for the salary I had coming to me under the five year contract I had with the White Sox,” he told Bisher. “When I won the verdict –I got only a little out of it –the first one I heard from was [American League President Ban] Johnson. He wired me congratulations on beating Mr. Comiskey and his son, Louis.”

For his part, Jackson did not consider himself a tragic figure. “I have read now and then that I am one of the most tragic figures in baseball. Well,” he said, “maybe that’s the way some people look at it, but I don’t quite see it that way myself. I guess one of the reasons I never fought my suspension any harder than I did was that I thought I had spent a pretty full life in the big leagues.”

His baseball career was close to its natural end, regardless of the ban. As Jackson saw it, “I was 32 years old at the time, and I had been in the majors 13 years; I had a life time batting average of .356; I held the all-time throwing record for distance; and I had made pretty good salaries for those days. There wasn’t much left for me in the big leagues.”

Of his fellow “Black Sox” Jackson said “ None of the other banned White Sox have had it quite as good as I have, I understand, unless it is Williams. He is a big Christian Science Church worker out on the West Coast. Last I heard Cicotte was working in the automobile industry in Detroit. Felsch was a bartender in Milwaukee. Risberg was working in the fruit business out in California. Buck Weaver was still in Chicago, tinkering with softball, I think. Gandil is down in Louisiana and Fred McMullin is out on the West Coast. I don’t know what they’re doing. “

Jackson summed the 1949 interview up by telling Bisher his conscience was clear. “I can say that my conscience is clear and that I’ll stand on my record in that World Series,” he said. “I’m not what you call a good Christian, but I believe in the Good Book, particularly where it says ‘what you sow, so shall you reap.’ I have asked the Lord for guidance before, and I am sure He gave it to me. I’m willing to let the Lord be my judge.”

When Jackson died two years later on December 5, 1951, Bisher wrote in the obituary published in the Atlanta Journal Constitution that he believed Jackson died with a clear conscience:

Shoeless Joe Jackson was a plain and simple man who thought in plain and simple ways. . .

But without a bat in his hands, he had a weakness. He relied heavily on his friends for mental guidance. Any person kind to him got in return warmth and trust, and it has since been proven that Joe’s trust was in bad hands. . .

I’m sure that he went to his death the other night in Greenville, S.C., still clear of conscience. I’m sure that when and if he did accept a spot of cash for an intended part in fixing the scandalous World Series of 1919 between his Chicago White Sox and the Cincinnati Reds he did so without realizing that he was committing a wrong. He was that simple a man, and that trusting in the teammates he thought he knew so well.

By whatever means Jackson’s 1920 grand jury testimony was obtained, it is difficult to come to any conclusion other than that “Shoeless Joe” took $5,000 in cash in return for his promise to throw the 1919 World Series. That he performed with excellence throughout the Series despite accepting the cash suggests that he did not act on that promise.

When Jackson told young Furman Bisher in 1949 that “I would have said it ain’t so, all right, just like I’m saying it now,” he was denying that he did anything to throw the 1919 World Series. He was not, however, denying that he took the $5,000.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.