The Soviet Union imprisoned Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn in the gulag after World War II, suppressed his writings during the Brezhnev years, and finally expelled him from his homeland in 1974. Forty years later, at the Sochi Winter Olympic Games, Russia celebrated its most famous dissident writer.

The Winter Olympics closing ceremonies featured a tribute to Russian writers, complete with papers swirling about the floor of Fisht Olympic Stadium. Spectators glimpsed giant portraits of, among others, Nikolai Gogol, Leo Tolstoy, Fyodor Dostoyevsky, Anton Chekhov, and Solzhenitsyn.

Breitbart Sports reached out to America’s foremost Solzhenitsyn scholar, Daniel Mahoney, to gauge his reaction to the Russian turnabout on the novelist and anti-Communist. A professor of politics at Assumption College, Mahoney co-edited The Solzhenitsyn Reader and authored Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn: The Ascent from Ideology and the forthcoming The Other Solzhenitsyn: Telling the Truth about a Misunderstood Writer and Thinker. Mahoney relayed that with the fall of the Soviet Union respect for Solzhenitsyn’s work has risen within Russia.

“Solzhenitsyn has his friends and enemies but he can be said to be esteemed in the new Russia,” Mahoney explained. “Three of his major books, One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich (the great novella about the Soviet camps), the beautiful Matryona’s Home, and the anti-communist classic Gulag Archipelago are all required reading in Russian schools. Solzhenitsyn had been enemy #1 of the Soviet regime but he is respected and admired by many in the new Russia.”

Sochi’s goodbye, like the spectacular opening ceremonies, weaved a narrative that at once celebrated the Russian past and broke from it. On the opening night, in the program’s most delicate balancing act, performers portrayed men under Communism as dehumanized cogs in a giant mechanized apparatus. The damned-if-they-do/damned-if-they-don’t depiction managed to artistically convey the meaning of the experiment Russians lived under for more than seven decades much more concisely than The Gulag Archipelago. Last night, Russia heralded writers–several of whom experienced persecution from Soviet and czarist authorities in their heydays–once silenced.

After his deportation, the bearded Nobel laureate laid down roots in Vermont. He found much to criticize, such as spiritual decline and cultural decadence, in the nation where his sons would become citizens. In his 1978 commencement address at Harvard University, Solzhenitsyn spoke truths that rubbed many of his hearers raw. “The communist regime in the East could endure and grow due to the enthusiastic support from an enormous number of Western intellectuals who (feeling the kinship!) refused to see communism’s crimes, and when they no longer could do so, they tried to justify these crimes,” he observed. “The problem persists: In our Eastern countries, communism has suffered a complete ideological defeat; it is zero and less than zero. And yet Western intellectuals still look at it with considerable interest and empathy, and this is precisely what makes it so immensely difficult for the West to withstand the East.”

The reversal in Russian elite opinion on Solzhenitsyn–from samizdat novelist to national hero in the course of a half century–displayed at the winter games underscores the massive changes that have taken place since the Russians last hosted an Olympic Games. In Moscow in 1980, many Western nations boycotted the event due to the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. Thirty-four years later, the Soviet Union is but a memory that few wish to remember.

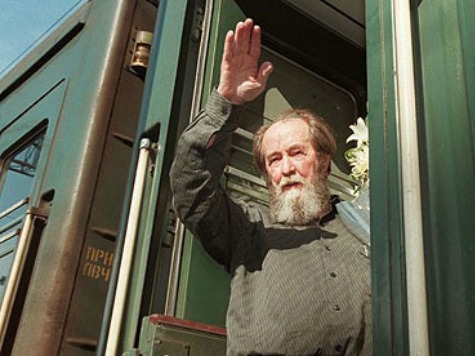

Solzhenitsyn, born into the Soviet Union in 1918, lived to see its demise. He repatriated in 1994 and spent his remaining fourteen years in the land of his birth. “He had his complaints about contemporary Russia (in his view not enough had been done to build democracy from the bottom up or to repent for the crimes of Communism) but he preferred the Putin years with all their imperfection to the massive criminality of the Yeltsin years,” Mahoney told Breitbart Sports. “To the day he died he remained an inveterate anti-Communist.”

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.