A Houston attorney has filed a $50 million lawsuit against the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) in U.S. District Court in Texas on behalf of a former Longhorns football player.

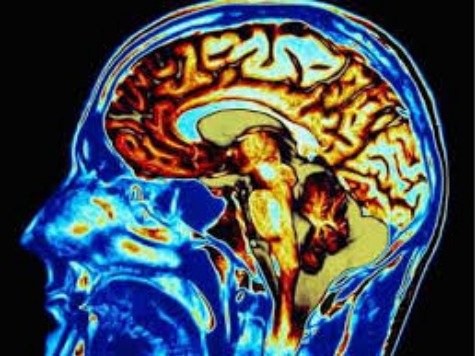

Julius Whittier, an attorney who broke the gridiron colorline at the University of Texas more than four decades ago, suffers from early-onset Alzheimer’s. The brief filed on his behalf, which aspires to class-action status, charges the NCAA with “concealment, inaction, and denial” regarding the dangers of football.

The suit alleges:

The NCAA has failed to educate its football-playing athletes of the long-term, life-altering risks and consequences of head impacts in football. They have failed to establish known protocols to prevent, mitigate, monitor, diagnose and treat brain injuries. As knowledge of the adverse consequence of head impacts has grown, the NCAA has never gone back to its former college football players to offer education, medical monitoring or medical treatment. In the fact of their overwhelming and superior knowledge of these risks, as compared to that of the athlete, the NCAA’s conduct constitutes negligence and reckless endangerment.

Whittier, who decided to go to UT after his senior season in high school when 36 players died across America as a result of hits at all levels of the game, played “unaware of the serious risk,” the litigation maintains. The suit faces hurdles, such as a statute of limitations on an injury allegedly endured more than four decades ago and the difficulty of proving that a 64-year-old man acquired Alzheimer’s disease through college football rather than from myriad other ways that 64-year-old men develop Alzheimer’s. The most thorough study concerning Alzheimer’s and football looked at nearly 3,500 pension-vested NFL players who competed between 1959 and 1988. The researchers at the National Institutes of Occupational Safety and Health expected to find 10 neurodegenerative-disease deaths based on prevailing societal rates. They found 12, of which Alzheimer’s claimed a fraction.

Atop obstacles in process and in proof, the filing hamstrings itself by relying on claims pushed in the media but discredited in scientific journals. The brief, for instance, claims that “CTE is also associated with an increased risk of suicide.” Repeatedly, academic articles released the last two years have rebutted this notion.

- “Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy and Suicide: A Systematic Review,” an article in BioMed Research International, found “scant evidence” suggesting a relationship between CTE and suicide. The authors note that “the current state of the science indicates that suppositions invoking a relationship between CTE and suicide must be viewed as speculative at this point in time.”

- A 2013 article in the Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society co-authored by a MacArthur “genius” fellow, points out about CTE: “The claim of heightened suicidality is particularly interesting given the fact that retired NFL players have significantly lower risk of suicide (less than half the expected rate) than the general population of men their age in the United States.”

- “NFL players are at decreased risk, not increased risk, for completed suicide relative to the general population,” Grant Iverson, a professor at Harvard Medical School, explained in a 2013 British Journal of Sports Medicine article. “Finding evidence of the neuropathology of CTE in the brains of former athletes who complete suicide is a provocative but not statistically compelling source of evidence,” he writes. “The putative causal link in individual cases represents circular reasoning (ie, petitio principii). At present, the association between the neuropathology of CTE and suicide has not satisfied basic criteria relating to the consistency, strength, temporality, specificity or coherence of the correlation.”

The suit also calls the degenerative brain disease “prevalent in retired football players.” But no cross-sectional or longitudinal study has even attempted to document the disease’s prevalence among the general public or football players. Indeed, the consensus statement of the 4th International Conference on Concussion in Sport informed of “an unknown incidence” of the disease and that “a cause and effect relationship has not yet been demonstrated between CTE and concussions or exposure to contact sports.”

“In sum,” the lawsuit against the collegiate sports behemoth declares, “the NCAA has known for decades that [concussions] in football can and does lead to long-term brain injury in football players, including, but not limited to, memory loss, dementia, depression, and CTE and its related symptoms.” At least with regard to CTE, the scientists do not know this. How, then, would the NCAA have known it 45 years ago?

Daniel J. Flynn, the author of The War on Football: Saving America’s Game (Regnery, 2013), edits Breitbart Sports.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.