The school choice reform movement, powered by grassroots activism, has made huge inroads in the past decade to break down the public school monopoly that has been failing America’s children. By giving parents choices – through charter schools, vouchers, Education Savings Accounts, and many other innovative methods – American students are receiving a more effective education that better suits their individual needs.

However, a series of 19th century laws, directed primarily against Catholics, is a major roadblock to future reform. Lindsey Burke of the Heritage Foundation and Breitbart News’ Jarrett Stepman have released a peer-reviewed article in with the Journal of School Choice outlining the impact of these obsolete laws, their ignoble origins, and suggestions for how states can deal with these 19th century relics. Commonly referred to as “Blaine Amendments”—a nod to the Maine politician James G. Blaine who tried to get a similar Constitutional amendment passed on the national level—these laws essentially prevent state aid from going to school choice programs because of the possibility of the money getting into the hands of “sectarian” religious schools.

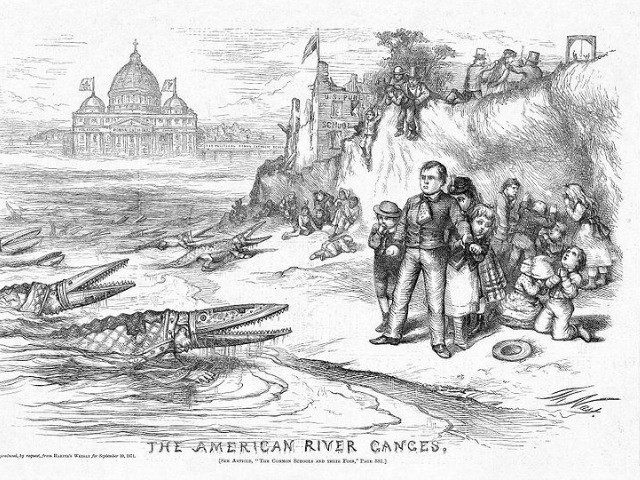

Today, there are 38 states that have some form of Blaine Amendment on the books, and the laws have been a serious obstacle in the way of school choice initiatives. Burke and Stepman’s paper highlights the history of the Blaine Amendments and their link to anti-Catholic nativists in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

In the Supreme Court case Mitchell v Helms, in which the Court ruled that it was permissible for government loans to be made to religious schools without violating the Federal Constitution’s Establishment Clause, Justice Clarence Thomas wrote that consideration of the Blaine Amendment “arose at a time of pervasive hostility to the Catholic Church and to Catholics in general.” He wrote that the doctrine underlying this proposed law and the state-level Blaine amendments was “born of bigotry,” and should be “buried” now.

In the earliest days of the Republic parents primarily financed their children’s education directly, and it was common for state and local government to fund private schools—most of which were religious. Americans at the time tended to be Protestant and there was little debate about whether or not this funding was proper. However, in the 1820s education reformer Horace Mann started the Common School movement. Mann’s reforms were an effort to centralize America’s system of education and to put the teaching of children in the hands of society and the state rather than leaving it to parents.

Mann based his reforms on six “principles,” that were becoming popular in central Europe:

Citizens cannot maintain both ignorance and freedom; (2) Education should be paid for, controlled, and maintained by the public; (3) Education should be provided in schools that embrace children from varying backgrounds; (4) Education must be non-sectarian; (5) Education must be taught using tenets of a free society; and (6) Education must be provided by well-trained, professional teachers.

By non-sectarian, Mann meant that public schools would essentially teach non-denominational Protestant Christianity. The early common schools were by no means secular, as modern day advocates of strict separation between church and state often suggest. Only Catholicism, however, was viewed as “sectarian.” Most Common School backers saw the teaching of religion in school to be absolutely vital, so long as it avoided more fractious doctrinal disputes.

Charles Leslie Glenn Jr. wrote in his book, The Myth of the Common School, that the “heart of this program, which we will call the ‘common school agenda,’ is the deliberate effort to create in the entire youth of a nation common attitudes, loyalties, and values, and to do so under the central direction of the state.”

There was much merit to this idea of inculcating values a citizenship and loyalty to the United States and there was a strong push in the early 19th century to teach following generations what it meant to be an American. Burke and Stepman wrote that as “historians Diane Ravitch and Joseph P. Viteritti (2011) note, schools were the ‘principal purveyor of deeply cherished democratic values. For many generations of immigrants, the common school was the primary teacher of patriotism and civic values.’”

As more Catholic immigrants began arriving on America’s shores in the mid-19th century, the battle over education heated up. Catholic schools wanted equal access to the funding Protestant schools received, which prompted anti-Catholic and nativist groups like the Know Nothing Party to propose laws preventing money from going outside the public schools.

Maine Congressman and Speaker of the House James G. Blaine attempted to channel these sentiments in his 1876 presidential run by sponsoring an amendment in the House that read:

No State shall make any law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; and no money raised by taxation in any State for the support of public schools, or derived from any public fund therefor, nor any public lands devoted thereto, shall ever be under the control of any religious sect; nor shall any money so raised or lands so devoted be divided between religious sects or denominations.

The amendment failed to pass in the Senate by just a handful of votes, and the national movement died after the election. However, states picked up the language of the amendment and included similar language in many state constitutions. Though modern-day Blaine amendment proponents argue that passage of the Blaine Amendments was an important and principled step for ensuring separation of church and state and the secularization of schools, Burke and Stepman make it clear that this was not the primary purpose behind the laws.

With the growth of the school choice movement in the last six decades and its rapid success in improving the education opportunities for Americans of all backgrounds, the Blaine Amendments must come under greater scrutiny because of the challenge they present to a long over-due proliferation of school choice.

In the course of their paper, Burke and Stepman explain the origins of Blaine Amendments, their impact, and how they hamper reform, and make suggestions about the steps that states can take to reverse their unfortunate impact. They recommend outright repeal of Blaine Amendments, adding provisions allowing for school choice in state constitutions, and making provisions for education funding to follow the child to an educational option of choice. This final option includes creating programs such as Education Savings Accounts that can be accessed and used by parents throughout their child’s education, an option that is already in place and working well in Arizona and Florida.

Burke and Stepman argue that for school choice to flourish and meet the needs of 21st century students the Blaine Amendment relics will have to be overcome. It is up to policymakers and grassroots activists to organize and defeat them, state by state.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.