On Thursday night, President Trump commemorated the 75th anniversary of the Battle of the Coral Sea. Speaking from the deck of the World War II aircraft carrier Intrepid, permanently berthed in the waters of New York Harbor, Trump paid tribute to the sailors and airmen who fought in that long-ago combat; indeed, seven of the old salts, now in their nineties, were in the audience, and Trump respectfully named each one.

Trump also paid due tribute to the 656 Americans who lost their lives in that battle against the Imperial Japanese Navy, which stretched over four days, May 4 to May 8, 1942.

Veterans are celebrated during a dinner to commemorate the 75th anniversary of the Battle of the Coral Sea, May 4, 2017 (Photo: Brendan Smialowski/AFP/Getty Images)

One of “the heroes that never returned,” the President recalled, was a Navy flyer, Jack Powers, who was killed as he dive-bombed an enemy ship. Later that year, the 32nd President, Franklin D. Roosevelt, paid tribute to Powers in a nationwide radio address. And now, speaking of all the heroes of that battle, the 45th President declared that it’s the duty of Americans to “keep their history alive.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nppUIaafGso

In addition, the President honored the gallant Australian contribution. That’s right and proper, too, especially since the Aussies have honored us. Indeed, earlier this month, American veterans of the battle were feted at a ceremony Down Under. And so on Thursday, it was gratifying to see Australia’s Prime Minister, Malcolm Turnbull, at Trump’s side; Trump recalled that for more than a century now, America and Australia have been on the same side in all our wars. As the President put it, “Our brave warriors have fought shoulder to shoulder.”

The Battle of the Coral Sea is most significant for two reasons:

First, during World War II, the engagement thwarted the planned Japanese attack on Port Moresby, on the island of New Guinea, just north of Australia. If the Japanese had taken Port Moresby, they would have been in a strong position next to invade Australia, which would have been catastrophic not only for Australians, but also for the war effort, as that country was the base of U.S. operations in the Pacific Theater.

Second, Coral Sea was the first naval battle in which the participating ships never sighted each other, nor fired upon each other. Instead, the engagement was fought almost entirely with aircraft launched from aircraft carriers; surface ships and submarines played only a supporting, albeit still vital, role.

Thus Coral Sea ranks as a profound hinge in the history of naval warfare. The era of the dreadnought, bristling with artillery, was over, and the era of the flat-top, launching airplanes, had begun. And as such, the relatively new specialty of naval aviation became paramount, along with all the attendant technological and industrial variables.

A United States Navy plane’s missile of death scores a hit against the Japanese aircraft carrier Shoho, in plume of smoke (center) during the battle of the Coral Sea. (AP Photo)

A wrecked Japanese war plane floating in the water after it had been shot down during the Battle of the Coral Sea. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

Of course, as usually is the case with technological transitions, the indicators, while evident, were not universally recognized. Many still thought of the battleship as the unchallengeable queen of the seas. This perception had survived the British success against the Italian fleet anchored in the harbor of Taranto; in that November 1940 action, British airplanes launched a surprise attack—as distinct from a “sneak attack,” as war had long before been declared—sinking or damaging eight Italian ships.

Unfortunately, even after that British aerial success at Taranto, American admirals were slow to draw the conclusion that surface ships were highly vulnerable from the air. As we all know, a year later, on December 7, 1941, the U.S. fleet anchored at Pearl Harbor was caught unaware in the Japanese attack that will live in infamy. A total of 19 of our ships were sunk or damaged, and more than 2300 Americans lost their lives.

Still, the final proof that the airplane was the new queen of the seas was yet to come. On December 10, 1941, Japanese torpedo bombers easily sank two heavy British warships in open water, in the South China Sea.

So the details of the epic engagement in the Coral Sea are worth recalling. At the direction of Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, the planner of Pearl Harbor, the Japanese invasion force, spearheaded by two fleet aircraft carriers, Shokaku and Zuikaku, steamed toward Port Moresby.

Fortunately, the Japanese battle plan was decrypted by a brilliant American officer, Navy Captain Joseph Rochefort. In response, Admiral Chester Nimitz ordered his forces, including two carriers, Lexington and Yorktown, into interposition.

In the resulting action, three American ships were sunk, and one carrier, Lexington, was so severely damaged that it had to be scuttled. Japanese casualties were comparable, but the main thing was that the invasion force turned back. Thus the battle rates as a strategic victory for the U.S.—the enemy retreated. No wonder the valorous name, Coral Sea, has since graced the bow of three Navy ships.

The USS Lexington, U.S. Navy aircraft carrier, explodes after being bombed by Japanese planes in the Battle of the Coral Sea in the South Pacific. (AP Photo)

A repair crew works on the deck of the USS Lexington aircraft carrier, after a Japanese bomb struck a glancing blow during an early phase of the battle of the Coral Sea. A number of Marine gunners were killed near the five-inch gun in the foreground. Later the Lexington was lost in a fire and explosion resulting from the battle. (AP Photo)

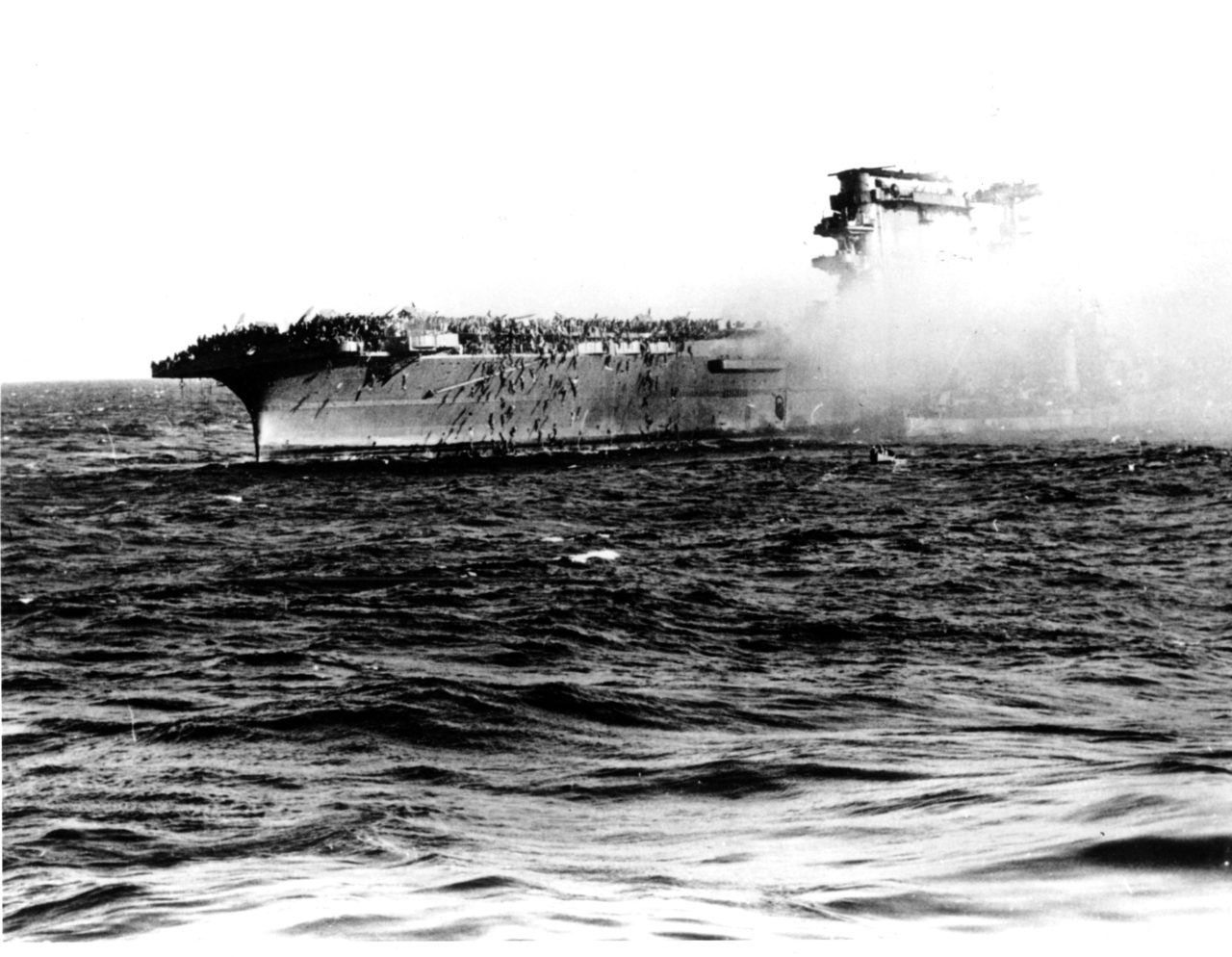

The crew abandons the USS Lexington after the decks of the aircraft carrier sunk in the Battle of the Coral Sea. Crew members wait to climb down on ropes on the side of the ship that is in flames from Japanese bombs. Some men are already aboard the Destroyer, hidden in smoke at right. Ninety-two percent of the crew was rescued. (AP Photo/U.S. Navy)

Still, the Americans could have done better, and they knew it. There were lessons to be learned—and quickly. Recalling the fate of that vital carrier, naval historian Ronald H. Spector records, “Lexington was ultimately lost because her crew was not well trained in damage control and not as well equipped [with] fog nozzles, asbestos suits, portable fire pumps, and modern breathing apparatus.” In other words, we can see that the resilience of a fighting force is heavily dependent on its ability to muster the mechanical wherewithal of survival—all those nozzles, suits, pumps, and so on.

Historian Spector adds, “Over the next year, the U.S. Navy would institute enormous improvements in its damage control practices, making American ships the most survivable in history.”

Indeed, some of those improvements were evident almost immediately. A month after Coral Sea came another battle in the Pacific, Midway, which proved to be a decisive American victory.

We might note that one of the participating carriers in that fight was Yorktown; it had been damaged at Coral Sea, and yet after returning to base at Pearl Harbor, the repairs were turned around in just two days, enabling the carrier to return to battle, and glory, at Midway. Thus we can see: Our ability to repair battle damage quickly helped make the difference.

The USS Yorktown in dry dock at the Pearl Harbor Navy Yard, May 29, 1942, receiving repairs for damage received in the Battle of the Coral Sea. She left Pearl Harbor the next day to participate in the Battle of Midway. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

Of course, beyond our ability to make rapid repairs, it was also vital that we could make new ships.

We might note that the U.S. entered into WWII with just seven aircraft carriers, and yet during the war, we built another 160 carriers, large and small. By contrast, the Japanese built just 25 carriers of various sizes. That’s a ratio of more than six to one—those are good odds.

Okay, but what about the airplanes on those carriers? We had more of them, too. And not only did we have them, but we made them better, quickly. Our carriers started the war flying mostly the F4F Wildcat fighter. It was a good plane, but we soon discovered that, in many ways, the Mitsubishi Zero fighter was superior. Not only did it have a longer range, but in addition, it could fly, turn, and climb faster.

However, thanks to our engineering aptitude and our industrial muscle, we quickly upgraded, ASAP. We soon introduced the F4U Corsair and the F6F Hellcat; by mid-1943, we enjoyed clear plane-to-plane superiority. And oh, by the way, we built more than three times as many fighters as did Japan. As they say, Quantity has a quality all its own. In addition, our greater logistical capacity soon made itself felt: unlike the Japanese, our pilots were rarely low on food, fuel, and ammunition.

It takes nothing away from the courage of our fighting forces to observe that our men had a lot of help on the homefront. We had all those defense plants, many of them “manned” by millions of Rosie the Riveters (to whom Trump has also paid tribute). Yes, many Americans working in the arsenal of democracy earned their Army-Navy “E” Awards. It was from those plants that we built the typhoons of steel and lead that smashed Imperial Japan, as well as, of course, Nazi Germany. And of course, the main reason that we had these many production plants in wartime is that we had them, first, in peacetime. A strong industrial base in peacetime can easily become a strong industrial base in wartime.

So it’s clear: If it takes skilled warriors to win, skilled manufacturers, too, are required.

This reality—for every soldier, there must be a worker, and a workplace—provides an important perspective on the enduring need for defense readiness. On the assumption that the the ancient Roman strategist, Flavius Vegetius Renatus, was correct when he declared, Si vis pacem para bellum (“If you want peace, prepare for war”), we should be thinking, always, about what we need to defend ourselves.

With such strategic needs in mind, it’s heartening to see that the Trump administration is thinking in these terms, including on matters of trade policy. Judgments about the importance of domestic production shouldn’t just be economic judgments; they should also be military judgements. And so, for instance, it was encouraging to learn that Secretary of Commerce Wilbur Ross has launched an investigation of aluminum imports. Just as it would have been foolish in the extreme to be dependent on Japan or Germany for vital materiel, so, too, it could be foolhardy to be dependent on any other foreign power today. In particular, it’s hard to argue with Ross’s supposition that dependency on China and Russia could well jeopardize our national security.

In that same security-minded vein, last month, too, Trump signed an executive order creating an Office of Trade and Manufacturing Policy in the White House. The head of that office is Peter Navarro, a longtime Trump economic adviser who has always emphasized the importance of national security in trade; indeed, he once made a documentary film entitled Death by China: One Lost Job at a Time.

As Trump declared when he signed the new order, the establishment of Navarro’s office “sends an important signal to the world that the United States will no longer tolerate trade cheating or allow our manufacturing and defense industrial base to wither and die.”

We might pause over those key words: “defense industrial base.” If we hadn’t had that defense industrial base in the 20th century, we would have lost our wars. And the same grim reality—the necessity of always preparing for war, for the sake of peace—holds true, as well, in the 21st century.

So just as the courage and sacrifice of the Battle of the Coral Sea must never be forgotten, we should also always remember the importance of military preparedness and productive capacity. Because danger always lurks.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.