With the passing of Prince on Thursday morning, the entertainment world lost not just one of its most prolific and inventive artists, but also one of its fiercest champions for individual freedom and artistic control.

In the wake of his untimely death at the age of 57, accolades and tributes have poured out from almost every corner of the world, including from President Obama: Prince was a “game-changer,” “one-of-a-kind,” “brilliant and larger than life.” An “electrifying performer.”

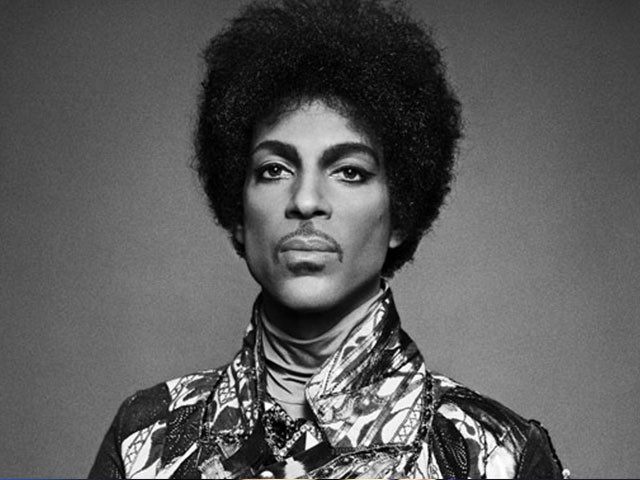

But Prince — full name Prince Rogers Nelson — was far more than that. The 5-foot-2 entertainer with the boyish good looks, devilish guitar chops and androgynous style was also an uncompromising advocate for personal freedom and self-empowerment in what would become an era defined by increased corporatization and centralized control.

In the early 90s, Prince famously battled with his record label, Warner Bros., over his contract, which he felt was restricting his creative output. He had just changed his name to an unpronounceable “symbol” — a “love symbol,” as it came to be known — and was sitting on roughly 500 unreleased songs, locked away at his Paisley Park Studios compound in Minnesota.

Prince reportedly wanted out of his contract with Warner Bros., and so wanted to use some of those unreleased tracks to fill out a few albums, and then formally end his relationship with what was then the largest record label in the world. Warners wanted to space the releases out to leave time for touring and other hype-building promotional activities; the label also wanted music from “the Symbol,” as that was what the artist was calling himself at the time.

The relationship was tense, to say the least. At the time, Prince had taken to writing “slave” on his cheek during several public appearances.

But more than anything else, Prince was most disturbed by the fact that he did not own the master tapes of his own music, despite recording most of it in his own studio. This development devastated him and forever changed the way he conducted his business, as author Ronin Ro noted in his biography of Prince, Prince: Inside the Music and the Masks.

“He really changed then,” engineer Tom Tucker told Ro. “At that point, he took control. He started signing the checks, literally.”

This episode may have provided the inspiration for one of his best quotes: “If you don’t own your masters, then your master owns you.”

After a rough few years that saw the release of a 3-disc greatest hits compilation and a trio of commercially unsuccessful albums (Come, The Black Album and Chaos and Disorder), Prince was finally released from his Warner Bros. contract in 1996. (The name-change episode was particularly frustrating for the record label, who reportedly had to send out a mass mailing of floppy disks containing the artist’s new “love symbol” to journalists, as most font collections could not reproduce it).

In the late 90s and early 2000s, Prince began releasing music on his own label, NPG Records, and set up his own Internet distribution outfit, NPGMusicClub.com. 1997 saw the release of the highly successful 5-disc Crystal Ball, which Prince distributed online through his subscription service. He also released two records in one-off deals with major labels Arista and Columbia (the low-selling Rave Un2 the Joy Fantastic and the successful Musicology, respectively) and continued to tour. He also retired “the Symbol” and began using the name Prince again.

In 2006, Prince earned a Webby Lifetime Achievement Award for his groundbreaking use of the Internet. In its dedication, the Webbys said the artist had “forever altered the landscape of online musical distribution as the first major artist to release an entire album exclusively on the Web.”

But in late 2006, Prince shut down his NPGMusicClub.com outfit and began a kind-of guerilla-style method to releasing his music. He had a new album out on Universal, the commercially successful 3121, and headlined both the Super Bowl halftime show in 2007 and the Coachella Music Festival in 2008. He began using radio appearances to release previously unheard music, and in 2009, launched another website, LotusFlow3r.com, where he debuted even more new music.

But by 2010, Prince had soured on the Internet. At the time, most record labels and industry executives thought services like iTunes and YouTube would be the savior of recorded music sales, and artists hoped the services could increase their reach in an increasingly technology-dominated marketplace.

But Prince was not convinced. In a 2010 interview with the Mirror, he famously declared the Internet to be “completely over” in a statement that was widely derided at the time by casual fans and technology observers but known to be horrifying fact by those employed in the music industry.

“I don’t see why I should give my new music to iTunes or anyone else. They won’t pay me an advance for it and then they get angry when they can’t get it,” he said then.

Three years later, he clarified and qualified his statement in an interview with the Guardian: “What I meant was that the internet was over for anyone who wants to get paid, and I was right about that,” he told the paper. “Tell me a musician who’s got rich off digital sales. Apple’s doing pretty good though, right?”

He was clearly ahead of the curve. Many of today’s top-selling artists, including Taylor Swift and Adele, have now similarly stood up to Apple and other online music giants to demand more artist-friendly deals.

But Prince’s refusal to play by the rules extended beyond his musical output and into his personal life. The unusually (for a pop culture icon) private star was reportedly a religious Christian and, around 2001, became a Jehovah’s Witness, an event he described to the New Yorker in 2008 as more of a “realization” than a “conversion.”

When pressed on his political leanings, Prince said that neither Republicans nor Democrats are “right.” Republicans, he argued, base too much of their lives on the Bible, which would not be a bad thing if it were not so open to interpretation and alternative understandings. Democrats and liberals, he argued, indulged in an anything-goes mentality that is harmful to society.

He was attacked relentlessly in the media for expressing his opinion on gay marriage. He said he had not voted for California’s Proposition 8, which affirmed the traditional definition of marriage in the state, because as a Jehovah’s Witness he did not vote at all, including in presidential elections.

But he also went further: “God came to earth and saw people sticking it wherever and doing it with whatever, and he just cleared it all out,” he told the New Yorker. “He was like, ‘Enough!'”

Prince was forced to clarify his comments in an interview with the Los Angeles Times shortly afterward: “I have friends who are gay and we study the Bible together,” he told the paper. “They try to take my faith… I’m a Jehovah’s Witness. I’m trying to learn the Bible. It’s a history book, a science book, a guidebook. It’s all the same.”

But the musician knew then what most “politically incorrect” public figures know now: that the wrong comment, political view or opinion can get you drummed out of town, excommunicated and shunned, no matter how many millions of records you’ve sold or any other public good you’ve provided. And from then on, he largely kept his political opinions to himself.

Most importantly, Prince was far ahead of the curve in understanding the danger of the era of corporatization, or, more specifically, the level of progressive fascism that this corporate control has now engendered.

Conservatives have been somewhat late to the game in understanding this; corporations, we argue, are a product of free-market capitalism and must, therefore, be “the good guys.” But it is frighteningly easy these days to see how many sectors of our public culture have been overrun with a strain of corporate progressivism that is just as pernicious as anything big government could conjure up.

Take, for example, the news this week that baseball legend Curt Schilling was fired from sports broadcaster ESPN for comments he made that were critical of supposed “anti-transgender” legislation. Or the evidence that social media giant Facebook has censored critical comments about the European migration crisis.

Legally, this is all fine and well. No one’s First Amendment rights are legally being violated because these companies are not required to provide a platform for speech they don’t approve of. They’re free to operate in whichever way they choose.

But this argument misses a critical point; namely, that these corporate giants exert an almost inescapable level of influence over the way in which ordinary people go about their lives and the way in which we communicate and transmit ideas as a culture.

Facebook, ESPN, Disney and other companies are free to pursue bolstering their bottom lines in any way they see fit. That is the beauty of capitalism. However, it is worth examining what this level of corporate pressure brings to bear on individual freedom, personal control and self-fulfillment.

Prince was one of the few artists (Frank Zappa also comes to mind) who understood the relationship between personal liberty and what can, at times, be rightly characterized as the totalitarianism of corporate homogeneity. It is for this reason that his death is as much a blow to the music world as it is to freedom lovers everywhere.

Follow Daniel Nussbaum on Twitter: @dznussbaum

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.