Third of Four Parts…

A Defining Event in Everyone’s Healthcare

Let’s start with the central moment of healthcare as experienced by most Americans. The patient goes to a medical office and says, “Please, doctor, I have this ache, pain, or lump. Is there anything you can do to help me?”

We can quickly see that this healthcare experience—including, also, seeking advice for wellness and overall longevity, for oneself or for a loved one—almost always comes prior to any consideration of paying the bill.

Instead, one’s instinctive and immediate focus is on health; that is, we are more naturally interested in the fruits of medical science—is there anything you can do?—than in the dollars-and-cents of accountancy finance.

To put the issue another way, the patient regards his or her problem as, first and foremost, a health issue and then, and only then, a financial issue. After all, the reason for going to the doctor in the first place is not to wrangle over the eventual bill; that might come later. In the here and now, the purpose of the visit, of course, is to get better.

We can observe that this is basic human nature: If you’re in a theater and someone yells “Fire!” your first instinct is flight, to survive; worrying about getting a refund on your ticket can wait till you’ve escaped the danger.

Thus the implicit science of a medical situation—can the doctor help me or not?—is prior to the finance; flesh, blood, and pain take priority over money, debt, and numbers on a ledger.

“Healthcare Policy Is a Loser for Whichever Party Is in Charge”

In the first and second installments of this series, we focused on the difficulty the Republicans are having as they seek a repeal-and-replace—or is it repeal-and-repair?—plan for Obamacare.

We might observe that the Republican difficulties of today, over health insurance, mirror the Democrats’ difficulties of eight years ago.

Then, it was the Democrats who had control of all three power centers in DC—that is, both chambers of Congress, plus the White House. And back then, the Democrats used their political power to enact Obamacare. And for their trouble, they were massacred in the 2010 midterms; they lost 63 seats in the House and six seats in the Senate. Furthermore, they were massacred again in the 2014 midterms. In fact, during the eight years of Barack Obama’s presidency, they lost a net of 69 seats in the House and a dozen in the Senate. Indeed, the Democrats are at their lowest ebb since the 1920s.

So now the Republicans have the power—and thus the responsibility—in Washington, DC. And they have made repealing Obamacare a prime objective.

So the political question is this: Does it mean anything, in terms of a flashing warning sign to Republicans about the upcoming 2018 midterms, that support for Obamacare is rising?

We can quickly observe that the increasing popularity of Obamacare—assuming, of course, that the polls are accurate—is probably more a function of the deepening polarization in the country, as opposed to a testament to the merits of the legislation itself. And yet we can just as quickly observe that even if so, it’s a distinction without much of a difference. That is, if people feel strongly about something, for whatever reason, they are more likely to get active and vote.

So could it be that anti-Obamacare Republicans going against the tide today, just as pro-Obamacare Democrats were going against the tide eight years ago? We’ll find out the answer in 21 months.

Yet in the meantime, this author is reminded of an observation made by a shrewd former Republican Member of Congress back in 2009: “Healthcare policy,” he told me, “is a loser for whichever party is in charge.”

It’s easy to see why he said that. After all, using health insurance, public or private, is, for most people, a tiresome burden. And so they groan when they hear the words “health insurance.”

Let’s ask ourselves: Who has had a happy experience dealing with a health-insurance bureaucracy? Who actually likes their health insurer? And if the insurer is the government—such as, say, the Veterans Administration—does that make it any better? Who likes the federal government? Is anyone surprised to learn that, according to a 2016 Gallup Poll, the feds ranked dead last among industries and institutions?

So if all that’s true, why would elected officials—especially Republicans—be in such a rush to link themselves, in the public mind, with health insurance? Sure, sure, they all say that their healthcare reform, including, perhaps, privatization, will improve the situation, but the voters don’t seem to agree; the voters aren’t inclined to trust anyone on health-insurance matters.

So yes, Obamacare-repealing Republicans might be feeling brave in 2017—and courage is always to be applauded—but it’s worth recalling that in 2009, Obamacare-enacting Democrats were feeling brave, too.

Indeed, Congressional Republicans who are gung-ho on smiting Obamacare might pause to consider a February 22 report from CNBC; the news item indicated that the Trump administration does not plan on putting forth a health-insurance bill of its own. In other words, the Obamacare ball is completely in Congress’ court.

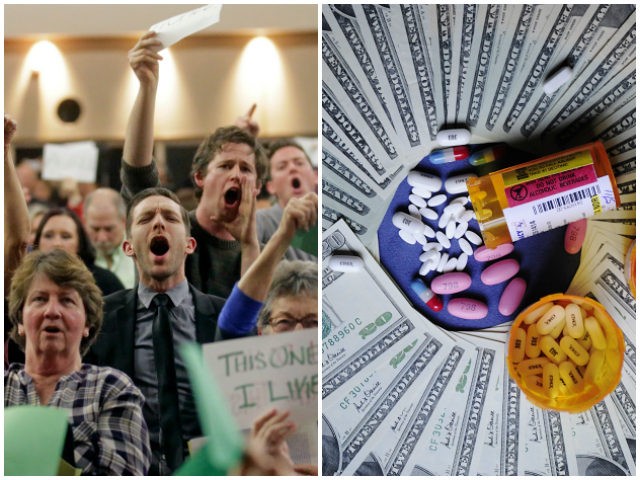

So it’s Republicans, now, who risk being on the receiving end, and they will have little political cover from the White House. And as a painful indicator of things to come, we might consider this tweet from CNN, featuring a video from a February 22 town hall in Springdale, Arkansas:

Voter to @SenTomCotton: My husband is dying. We can’t afford health insurance. What kind of insurance do you have?

We might note with admiration that Cotton, alone on the stage, maintained a stoic calm and a dignified composure, even as he was being jeered by two thousand people. And perhaps the crowd was, in fact, salted with George Soros-funded activists. Still, even if the entire crowd was bused-in astroturf, it means something when an audience erupts in an angry standing ovation, aimed against Cotton and in favor of Obamacare—and it’s all on TV and social media. At a minimum, we can say, there will be a lot fewer Republican town halls.

Is There a Better Way?

Perhaps Republicans could choose a different path. Or, if one prefers, more than one path. That is, where is it written that “healthcare policy” has to be defined only as “health insurance”?

That is, instead of focusing exclusively on health insurance, as they are now, perhaps Republicans could embrace a broader agenda: Perhaps they could focus on health. That is, they could emphasize more the science of cures and treatment, and emphasize less the politics of insurance and reimbursement.

If they were to choose the path of science, they would realize that many leaders have been down that road before. As far back as 1813, for example, Congress launched a nationwide vaccination campaign against smallpox, which had killed many Americans and crippled or disfigured many more. Medical science was a lot iffier in those days, and yet even so, by the end of the 19th century, the dreaded illness was almost completely eradicated in the US.

Further health campaigns, beginning after the Civil War, mostly involving hygiene, pushed back against other killers, such as hookworm, puerperal fever, tuberculosis, typhoid, and typhus.

Moreover, in the early 20th century, we figured out that if we drained swamps and other stagnant pools of water, we could get rid of malaria and yellow fever. In addition, we learned that with enough Vitamin D in our diet, we could stop the dreadful bone deformation caused by rickets.

And then, in the middle of the 20th century, we launched a successful private-public campaign, the March of Dimes, to develop the polio vaccine.

So today we might step back and ask: What would our lives be like now if we hadn’t made all those breakthroughs? Answer: Our life expectancy would be about 30 years shorter.

In 1971 came another milestone in improved public health: President Richard Nixon announced his “War on Cancer.” And while that effort, which at the time was endorsed by huge majorities in Congress, has been controversial—perhaps because it was Nixon who proposed it?—the facts say that it has been a success. Today, cancer is 36 percent more survivable than it was four decades ago. So if we haven’t yet won the war on cancer, we’ve at least won some major battles.

We might add: Whoever said that when launching a war—including a war against disease—one is guaranteed a quick victory? After all, our Cold War lasted the better part of a half-century. And across history, countries have been engaged in struggles that lasted even longer. The Hundred Years’ War between England and France, we might note, actually extended over 116 years.

And speaking of wars against disease, isn’t the struggle exactly that—a war?

We might consider: The disease is trying to kill us. So as a matter of pure self-defense, why shouldn’t we try to kill it? It’s better to strike than be struck.

Indeed, the sooner we start thinking of medical science as an arsenal for our ongoing war against disease, disability, and premature death, the sooner we will be able to use our collective firepower. That is, we can join an army that will help us combat the ultimate challenge to our health that each of us will face, sooner or later—the later the better.

So again, health insurance is important, but health itself is more important.

Indeed, in the case of certain maladies—but only for certain maladies—national policy has always been shaped by this war-on-disease idea. For example, in the 80s and 90s, we made an all-out effort against HIV/AIDS. For activists, the issue wasn’t insuring the cost of the disease as it ravaged patients, it was financing the defeat of the disease so people could stay healthy.

Thus we spent hundreds of billions of dollars, and the results have been spectacular. Today, for most of those infected, HIV/AIDS is a manageable condition. And all humanitarian considerations aside, the economic benefits of better treatments, across the board, have been enormous. The medical philanthropist Michael Milken reports that just from 1970 to 2000, the gains of better life expectancy and productivity added $3.2 trillion to our national wealth.

More recently, we’ve also made astounding progress against Ebola and Zika. Not long ago, those viruses were feared to be pandemic plagues; yet now, while each individual case is still a tragedy, the national impact of Ebola and Zika has been marginal.

So we can see: When we Americans put our collective shoulder to the wheel, the various sectors of our society—public, private, philanthropic—can achieve magnificent success. So why not have more of that? Against more terrible diseases? Among other considerations, wouldn’t that be a political winner for the disease-warriors?

And so it’s curious that when Republicans released the broad outlines of their pending healthcare plan on February 15, the words “research,” “medicine,” and “cures” were nowhere to be found. These omissions could be rated as a lost opportunity—politically, as well as, of course, medically.

We might further note that when activist Democrats released their critique of the GOP plan the very next day, they also made no mention of “research,” “medicine,” and “cures.” So it would seem that both parties, in their dueling fashion, are mesmerized by a single issue within the health space—that is, health insurance by itself.

And why is this? Why this preoccupation with finance, as opposed to science? Perhaps it’s because the policy-wonk class, on both sides of the aisle, is composed almost entirely of the legal- and financial-minded, as opposed to the medical- and scientific-minded. As the Talmud tells us, you see the world as you are. And so in DC, the healthcare policy papers reflect the legal-financial bias of the writers.

The Once and Future Cure Strategy?

Yet in fact, some Republicans have chosen to cut against the grain: They have raised the issue of curing disease. Indeed, they have not only raised the issue of cures, they have actually gotten something done on behalf of cures.

As noted in the first installment of this series, Donald Trump has repeatedly highlighted the prospect of more and better cures as part of an overall healthcare agenda. And as mentioned in the second installment, so has Sen. Ted Cruz.

It’s also worth recalling that during the previous session of Congress, two visionary workhorse Republicans, Rep. Fred Upton of Michigan and Sen. Roger Wicker of Mississippi, teamed together to craft the 21st Century Cures Act. That legislation tackled many important health goals, including a much-needed streamlining of the Food and Drug Administration, more basic research on the human brain, and stronger efforts to combat the opioid epidemic.

The Upton-Wicker bill sailed through both legislative chambers with massive majorities; in the House, the final vote was 392-26, and in the Senate, 94-5.

(As a purely political aside, we might observe that Republican strategists having reportedly chosen to target Democratic Senator Elizabeth Warren as the national emblem of bicoastal left-liberalism—which, of course, she is. And so it’s worth noting that she was one of those five “nays” against the Cures Act. So someone might wish to ask Warren what it was, in her ideology, that impelled her to vote against medical cures?)

This year, one might have thought that GOP lawmakers would seize the opportunity to build on the Upton-Wicker success, and perhaps they still will.

After all, there’s a lot more to be done on the cures front. For instance, former House Speaker Newt Gingrich—for decades an articulate champion of medical advancement—now warns that if progress isn’t made against Alzheimer’s Disease (AD), we are on a track toward spending, by mid-century, some $20 trillion. That’s $20 trillion, of course, that we don’t have.

The Value of Hanging Out with a Better Crowd

For further perspective on a maximal health policy, we might take note of a 2014 Gallup Poll, which found that of ten professions, the top three, in terms of honesty and ethics, were all health-related—that is, nurses, medical doctors, and pharmacists. In that same poll, we might add, Members of Congress were ranked in the cellar, behind even car salespeople. Indeed, whereas nurses, for instance, were rated “very high or high” by a full 80 percent of Americans, just seven percent felt that way toward lawmakers.

So again, putting aside all humanitarian and ethical considerations, one might think that elected officials would be jumping at the chance to associate themselves with esteemed medical professionals. That is, better a photo-op with a healthcare provider, talking about health, and not with just another politician, talking about health insurance.

Of course, the politician would need a reason to be there—and what better reason than announcing some ambitious new medical plan?

To put the matter even more bluntly, wouldn’t pols be better off talking about a Cure Strategy, as opposed to an Obamacare Strategy?

We might take a moment to declare: Nothing here is meant to minimize the importance of health insurance. In the end, there’s no free lunch, even if, as we have seen, medical advances have a way of paying for themselves.

So no, we can’t minimize health insurance, but we can contextualize it. For the reasons we have seen, in most cases, health insurance is secondary, not primary.

Moreover, nobody need worry that health insurance will be neglected. Why? Because health insurance is big enough to take care of itself. In 2016, the National Health Expenditure (NHE) of the US was $3.36 trillion. And of that mammoth total, some 90 percent was paid for by some form of insurance. That is, it’s paid by a third party, be it public, private, or charitable. With that much money at stake, people will always be plenty interested in health insurance. Indeed, we can also see just how hard it will be to make the slightest change in the healthcare status quo—because somebody, perhaps somebody powerful, is guaranteed to get mad.

To underscore this point about the embedded complexity of the health-insurance system, we might further note that the federal government accounts for 29 percent of the NHE, and state and local governments account for another 17 percent. So we can see, even if Obamacare were to be repealed in toto, the government would still be footing the bill for nearly half of all healthcare consumption.

In other words, Congress can work on Obamacare, pro and con, all it wants, and yet in the end, no matter who prevails, the overall health-insurance system won’t change much: People will still rely on health insurance, they will still dislike their health insurer, and health insurance will still be, substantially, a public undertaking.

So with that stubborn reality in mind, perhaps a lawmaker today might ask himself or herself: Wouldn’t I rather be working on, and voting for, a cure for disease? That is, for policies that promote research, entrepreneurship, and innovation to meet urgent public needs? Isn’t that a more soothing message to deliver to the folks at a raucous town hall?

So is there hope that a Republican Cure Strategy will emerge? We’ll have to wait and see, of course, but it certainly seems that the cures approach—as highlighted by Trump and Cruz, and as legislated by Upton and Wicker—offers Republicans more upside and less downside.

In the meantime, we only know this much: The American-style fusion of science, technology, and vision has worked in the past to promote progress, and it can be made to work, yet again, in the future.

Why so optimistic? We’ll take up that question in the next installment.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.