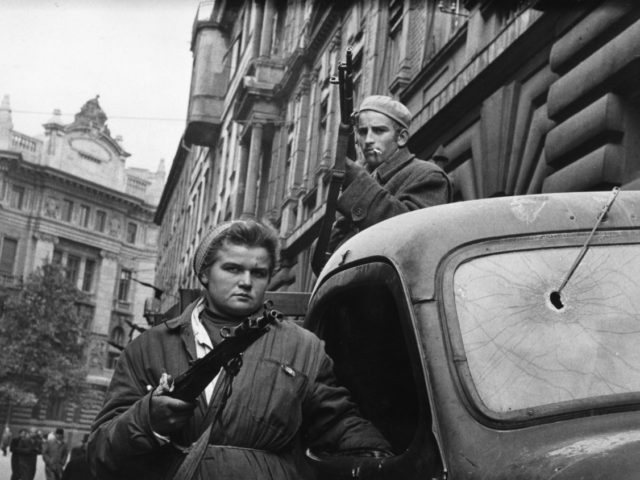

On this day in 1956, the Hungarian people rose up against their Soviet occupiers, an important chapter in the history of a country which jealously guards its freedom, and remains at odds with a European Union which continues to push for integration and conformity.

Statues were torn down, members of the brutal secret police lynched, and flags burned. Ordinary people also celebrated in the streets — until it became clear that support from the West to make the revolution permanent was not coming, and the Soviets sent in the tanks to put it down.

In the end, over 3,000 were killed in that ill-fated fight to make a country free.

Hungary and the rest of Central Europe eventually found its freedom when the Soviet Union finally crumbled in 1989, and years later were accepted into the European Union. But it has been clear since that Hungary — much like Poland — has not taken well to the EU’s particular idea of democracy.

A sculpted head of Stalin, knocked off its statue during an anti-Russian demonstration, lies in the middle of a road in Budapest. (Photo by Keystone/Getty Images)

Indeed, despite Hungarian leader Viktor Orbán enjoying the largest mandate of any elected leader in the European Union, Brussels has repeatedly threatened and attempted to cajole Budapest over hot-topic issues including mass migration.

Hungary is only the best example, perhaps, of a clear divide that exists in Europe — of nations that suffered under the brutal yoke of an oppressive left-wing state and know what it means to have national identity forcibly eroded, to have wrong-speech harshly punished, and to live by diktats issued by a remote and unaccountable bureaucracy.

Hungarians can enjoy a special pride in having endured that because they did rise up in 1956. Indeed, feeling over the 1956 revolution is so strong during 2006 anti-government corruption protests, a tank originally used in 1956 was taken from a museum and used to storm police lines.

Symbolism hardly comes stronger than that.

Last week the New York Times carried an opinion piece from a prominent Hungarian academic outlining the country’s important struggle for freedom, and outlining how hard it is for the nations of Western Europe to understand the Eastern European mindset — the craving for freedom briefly experienced after liberation and now being eroded by an increasingly overbearing European Union.

1956: A group of men hold a flag on top of a tank in front of the Parliament building during the Hungarian Revolt, Budapest, Hungary. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

Written by Hungarian historian Maria Schmidt, the director of the nation’s House of Terror Museum which memorialises the brutal suppression of the nation under the Communist police state, the article goes some way to explaining why Hungarians have become a caste apart in the European Union. In fact, her writing is so stridently unabashed and unselfconscious of the self-censoring norm in Western Europe, it is practically a breath of fresh air.

On the rising interest in populism among voters across Europe in recent elections, Schmidt wrote:

Voters sent a clear message: They want more flexibility in politics, less ideological dogmatism and more readiness for compromise.

While some may not be able to accept it, the old world is disappearing. It can’t be saved. What can and should be saved is Western (Christian) civilization. We must realize that, as the historian Niall Ferguson once wrote, “the biggest threat to Western civilization is posed not by other civilizations, but by our own pusillanimity — and by the historical ignorance that feeds it.”

We Hungarians are well aware that nobody has our best interests at heart other than ourselves. That’s why we continue to insist on liberty, democracy and our independence as a nation-state.

As citizens of a free country in the heartland of Europe, we have served as gatekeepers between East and West for a thousand years.

We hope to do so for a thousand more.

Read more at the New York Times

Beyond the usual celebrations attendant to a country celebrating an important historical day, we can also expect to hear from Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán today. His speech marking the 1956 anniversary in 2018 also proved instructive in the different, unashamedly traditionalist-populist mindset that is developing in Central Europe.

Addressing the European Union this time last year, Mr Orbán warned against the bloc transforming into a new “European Empire” and said in a speech delivered at the Terror House Museum: “Let’s choose independence and a cooperation of nations over global governing and control. Let’s reject the ideology of globalism and support the culture of patriotism.”

The Hungarian Revolution started on October 23rd 1956 and lasted until November of the same year, when Soviet troops including 1,000 tanks overran the country and put down what they characterised as a “counter-revolution” led by “reactionaries”. In addition to those killed during the fighting, thousands more were executed and imprisoned by the Soviet regime in the years following.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.