MEXICO CITY (AP) — Mexico now deports more Central American migrants than the United States, a dramatic shift since the U.S. asked Mexico for help a year ago with a spike in illegal migration, especially among unaccompanied minors.

Between October and April, Mexico apprehended 92,889 Central Americans. In the same time period, the United States detained 70,226 “other than Mexican” migrants, the vast majority from Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador.

That was a huge reversal from the same period a year earlier, when the wave of migrants and unaccompanied minors from Central America was building. From October 2013 to April 2014, the United States apprehended 159,103 “other than Mexicans,” three times the 49,893 Central Americans detained by Mexico.

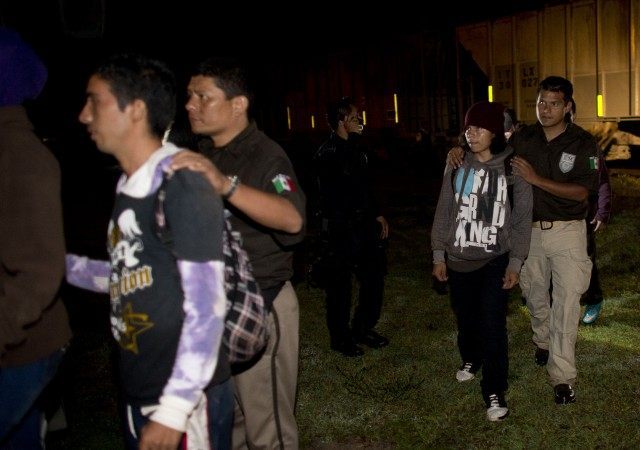

The difference is Mexico’s new Southern Border Program, an initiative that included sending 5,000 federal police to the border with Guatemala and more border and highway checkpoints. Raids on migrants increased and authorities focused on keeping migrants off the northbound freight train known as “the Beast,” on which many have suffered mutilation injuries.

Neither U.S. nor Mexican immigration officials responded to requests for comment on the change this week, though officials in the past have said it is aimed at reducing dangers facing migrants.

“Mexico is doing the dirty work, the very dirty work, for the United States,” said Tomas Gonzalez, a Franciscan friar who runs the “72” shelter for migrants in Tenosique, a town in the southern Mexico state of Tabasco.

In the past, Mexican migration officials looked the other way as thousands rafted across the river at the border and then boarded freight trains north. In 2014, more than 46,000 unaccompanied minors from Central America crossed into the United States, leading the U.S. government to turn to the governments in Mexico and Central America to try to stanch the flow.

Mexico has proved the more efficient in deportations, which is already causing concerns among human rights groups about the new tactics.

In most cases, Mexico holds migrants only long enough to verify their nationalities, and quickly bundles them aboard buses to take them back to their home countries.

“The time that foreigners are in immigration (detention) centers depends only on the speed with which the authorities of their (home) countries confirm their nationality,” Mexico’s National Immigration Institute said in an email response to questions from The Associated Press.

Maureen Meyer of the Washington Office on Latin America think tank, which noted the dramatic change in a report this week, questions the speed Mexico is using.

“What we have heard continuously in the past year is that migrants are being so rapidly deported that even some that might have wanted to request some type of protection, or who would have been eligible for some type of humanitarian visa because they had been victims of crime in Mexico, haven’t had that opportunity,” Meyer said.

By comparison, when immigrants are caught crossing the U.S. border illegally, the process of being sent home can take anywhere from hours to years. Mexican nationals are often repatriated quickly – sometimes the same day they are caught – while migrants from other countries often spend at least a few days in U.S. custody before being flown back to their country of origin.

The deportation process can take much longer if an immigrant seeks asylum or if the person is a child traveling alone. For those immigrants who fight to stay in the United States, the wait for a court date and a final decision on their case can take several years because of backlog of more than 449,000 cases already pending in immigration courts.

According to the U.S. Department of Justice, there were about 41,920 requests for asylum in 2014, not all from Central Americans. About 49 percent of requests processed that year were granted.

Mexico grants only a tiny number of asylum requests. The latest figures, covering a nine-month period from January to September 2014, show only 1,525 people, the majority of them Central Americans, requested asylum or refugee status, and only one-sixth – 247 – were granted.

U.S. officials did not respond to questions regarding the amount of U.S. funding Mexico receives for its crackdown on the Guatemalan border, but it is making things tougher for migrants..

“It has raised the costs of the trip, it has raised costs for paying coyotes (smugglers) and the (Mexican) authorities that let them through,” said Gonzalez, the migrant activist. “It has spurred increases in everything bad – corruption and impunity – everything but human rights.”

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.