Paris (AFP) – A tiny lander despatched to Mars on a trial run had crashed and possibly exploded on the Red Planet, mission control said Friday, confirming Europe’s second failed attempt to reach the alien surface.

The paddling pool-sized Schiaparelli craft “crashed on the surface of Mars”, Thierry Blancquaert told AFP from European Space Agency (ESA) mission control in Darmstadt, Germany — ending two days of uncertainty about the lander’s fate.

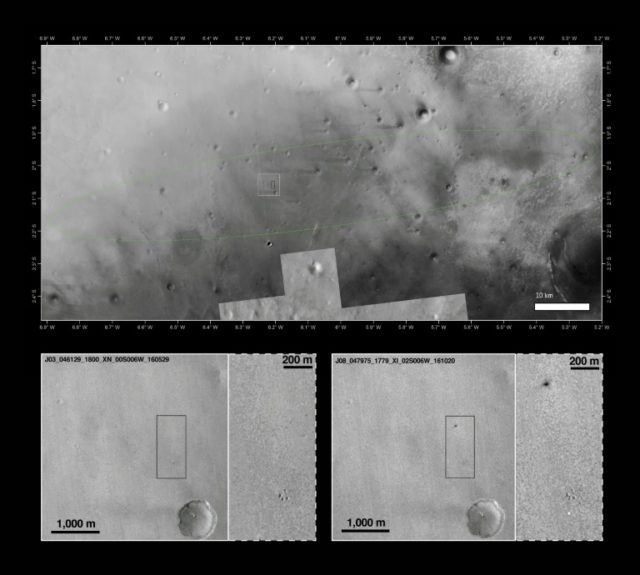

A NASA photograph of the intended landing site revealed the 600-kilogramme (1,300-pound) craft, offline for two days, had “reached the Martian surface a lot faster than intended,” he said.

The image contained a white spot, thought to be the doomed lander’s parachute spread out on the alien surface, some 170 million kilometres (106 million miles) from Earth.

About two kilometres (1.2 miles) from the white spot is a larger, black patch with fuzzy outlines, some 15 by 40 metres (49 by 131 feet) — interpreted as Schiaparelli’s crash site.

The black spot is “larger than it would have been if Schiaparelli was in one piece”, flight director Michel Denis told AFP. “It is smashed.”

The ESA said the lander’s speed-breaking retro-rocket boosters appeared to have switched off prematurely.

“Estimates are that Schiaparelli dropped from a height of between two and four kilometres, therefore impacting at a considerable speed, greater than 300 kilometres (186 miles) per hour,” it said in a statement.

“It is also possible that the lander exploded on impact as its thruster propellant tanks were likely still full.”

Engineers and scientists are combing through the data Schiaparelli sent home before its untimely demise, to piece together exactly what happened.

– Search for life –

Schiaparelli was on a test-run for a future rover meant to seek out evidence of life, past or present, on the Red Planet.

But it fell silent seconds before scheduled touchdown, while its mothership Trace Gas Orbiter (TGO) entered Mars’ orbit as planned.

The pair comprised phase one of a project dubbed ExoMars through which Europe and Russia seek to join the United States in operating a succesful rover on Mars.

Europe’s first attempt, in 2003, also ended in disappointment when the British-built Beagle 2 robot lab disappeared without trace after separating from its mothership, Mars Express, in 2003.

The 230 million-euro ($251-million) Schiaparelli had travelled for seven years and 496 million kilometres (308 million miles) onboard the TGO to within a million kilometres of Mars last Sunday, when it set off on its own mission to reach the surface.

It was scheduled to touch down at 1448 GMT on Wednesday after a scorching, supersonic dash through Mars thin atmosphere.

For a safe landing, Schiaparelli had to slow down from a speed of 21,000 kilometres (13,000 miles) per hour to zero, and survive temperatures of more than 1,500 degrees Celsius (2,730 degrees Fahrenheit) generated by atmospheric drag.

It was equipped with a discardable, heat-protective “aeroshell” to shield it, a parachute and nine thrusters to decelerate, and a crushable structure in its belly to cushion the final impact.

Since the 1960s, more than half of US, Russian and European attempts to operate craft on the Martian surface have failed.

Europe has insisted that any problems encountered by Schiaparelli were part of the trial-run and would inform the rover design.

“Schiaparelli’s misadventures will not call into question” the rest of the mission, Denis said Friday.

ESA director-general Jan Woerner said Thursday the agency will seek additional funding from European governments for ExoMars, for which Europe has budgeted 1.5 billion euros ($1.6 million) so far.

The next part of the mission is the start of the TGO’s science mission in 2018, sniffing Mars’ atmosphere for gases potentially excreted by living organisms.

The rover will follow, due for launch in 2020, with a drill to search for remains of past life, or evidence of current activity, up to two metres deep.

While life is unlikely to exist on the barren, radiation-blasted surface, scientists say traces of methane in Mars’ atmosphere may indicate something is stirring underground — possibly single-celled microbes.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.