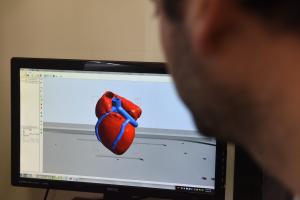

April 15 (UPI) — Researchers at Tel Aviv University have managed to 3D print a heart using a patient’s cells and biological materials — a first.

Scientists have previously built synthetic hearts and bio-engineered tissues using a patient’s cells. But the latest feat is the first time scientists have created a complex organ with biological materials.

“This is the first time anyone anywhere has successfully engineered and printed an entire heart replete with cells, blood vessels, ventricles and chambers,” lead researcher Tal Dvir, a material scientist and professor of molecular cell biology at TAU, said in a news release.

The proof-of-concept feat could pave the way for a new type of organ transplant. For patients with late stage heart failure, a heart transplant is the only solution. But there is a lack of heart donors.

“This heart is made from human cells and patient-specific biological materials. In our process these materials serve as the bioinks, substances made of sugars and proteins that can be used for 3D printing of complex tissue models,” Dvir said. “Our results demonstrate the potential of our approach for engineering personalized tissue and organ replacement in the future.”

The heart scientists printed couldn’t be used in a human transplant operation. Though completely vascularized, it’s too small at about the size of a rabbit heart.

“But larger human hearts require the same technology.” Dvir said.

Researchers detailed their breakthrough this week in the journal Advanced Science.

To create the bioinks used to build the heart, scientists took fatty cells from a patient and reprogrammed them to become pluripotent stem cells before differentiating them into cardiac and endothelial cells, which form the vascular interior. Scientists mixed the differentiated cells to form bioinks, which were layered onto scaffolding using a specialized 3D printer to form a small heart.

“The biocompatibility of engineered materials is crucial to eliminating the risk of implant rejection, which jeopardizes the success of such treatments,” Dvir said. “Ideally, the biomaterial should possess the same biochemical, mechanical and topographical properties of the patient’s own tissues. Here, we can report a simple approach to 3D-print thick, vascularized and perfusable cardiac tissues that completely match the immunological, cellular, biochemical and anatomical properties of the patient.”

Though the heart cells currently contract, they’re not synchronized or entirely functional. Scientists need to better program the 3D-printed heart and its varied components and cells to coordinate their movements, so the organ doesn’t just look like a heart, but acts like one too.

Once researchers print a heart that functions as it should, they can start testing their technology on real animal models.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.