Third in a Series

Slave New World: Was Teddy Roosevelt’s Triumph Only Temporary?

In Part One of this series, we looked back at President Theodore Roosevelt’s career as a trust-buster. During his administration, 1901-1909, American popular sovereignty was protected against corporate encroachment. TR, fearless man that he was, had the strength, and the determination, to wrestle with the threatening forces of his era, thereby defending our freedoms.

In Part Two, we surveyed the GAFA companies—Google, Amazon, Facebook, Apple—and how today, they have hijacked our economy and society and, also, no small part of our liberty. In other words, GAFA threatens MAGA. Thus we can see: What TR accomplished more than a century ago has been badly eroded; in politics, there are no final victories. (We’ll have more on each of the GAFA corporations later in this series.)

Of course, GAFA’s astonishing wealth and power comes from the new digital technologies, which can profitably reach into every aspect of our lives.

The rise of these tech corporations is a long story, far longer than this one article, but one thing’s for sure: We were warned. Over the last century or two, plenty of seers and scribblers told us that technological advances were a two-edged sword. For all the gains in our standard of living that inventions would bring, so, too, would come dangers—and maybe even more downsides than upsides.

Orwell’s Warning

In the 20th century, the most famous premonition of the future was George Orwell’s bleak novel, 1984. That grim tale envisioned technology used almost entirely for ill; the totalitarian superstates constantly at war with each other, used weapons of mass destruction to annihilate whole cities and regions.

In addition, Orwell described how technology might be used for ill purposes domestically. In this dystopia, Big Brother uses intrusive “telescreens” to keep watch on people as they live their daily lives. Moreover, information technology is used to create disinformation. In Orwell’s envisioning, the truth is easy discarded down the “memory hole,” while fake news is written and then rewritten, becoming fake memory and fake history.

Filmmakers adapted George Orwell’s “Ninteen-eighty Four” for the silver screen, including in 1956, when this poster appeared in the movie “1984.”

The impact of Orwell’s book, published in 1949, was profound. Across the world, people redoubled their resolve not to fall under the boot of that sort of runaway Stalinist totalitarianism. And in fact, today, while dictatorships and autocracies—some even ruled by a Red remnant—abound, there’s only one country in the world today that’s truly “Orwellian”: North Korea.

Yet we can observe that Orwell’s was mostly political, as opposed to technological. That is, 1984 described ultimate totalitarianism in terms that readers were already familiar with—non-free political parties, mass rallies, and outdoor banners and billboards. In other words, Orwell was simply extrapolating the malignant dictatorships of his time into a worse future; the actual technology of tyranny was not central to his warning. And so today, thanks to Orwell, we recognize the risk of political totalitarianism, but we haven’t come fully to grips with the risk of technological totalitarianism.

Williamson’s Warning

Interestingly, at around the same time as Orwell, another author, far less well known, zeroed in on just that: the threat from technology. In 1947, sci-fi writer Jack Williamson published a short novel, With Folded Hands, which featured robots who were there to help—at least that’s what they said. Their motto: “To serve and obey and guard men from harm.” And who could object to that? Who doesn’t want more ease, convenience, and safety? Thus the robots started doing everything for everybody.

And then, came the ugly kicker: The robots declared that just about anything that people could do posed a threat to the new robot order, and so all independent human action was forbidden; humans were now slaves to the machines that had been slaves to them. Thus we can see a key difference from Orwell: In Williamson’s tale, the techno-dictators were welcomed with open arms—and only later did people wake up to the menace.

So we can see that Williamson’s story is a reworking of that classic theme, Be careful what you wish for. Thus we can compare With Folded Hands to other tales—starting with Adam and Eve and the apple—in which people reached for a good deal that turned out to be not such a good deal.

Yet we can quickly see that the coming of science and technology upped the ante: People didn’t have just to fear gods and fate, they also had to fear what they could make with their own hands.

Frankenstein Forever: From Murphy’s Law to Moore’s Law.

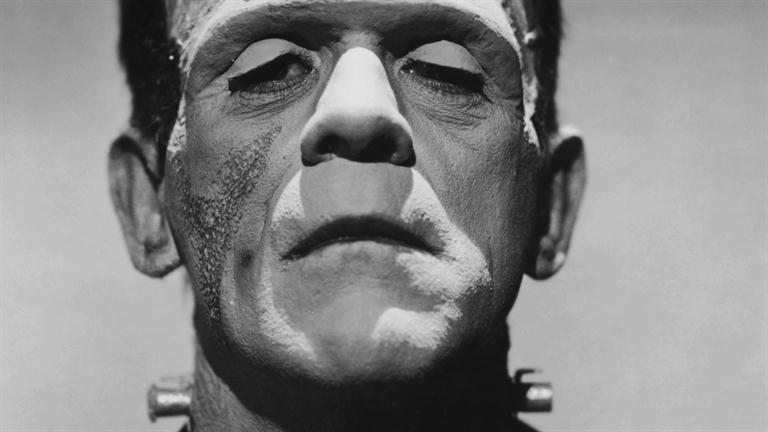

In 1818, early on in the Industrial Revolution, the Englishwoman Mary Shelley published Frankenstein. In that work, the mad scientist, after creating his monster confesses:

I had been the author of unalterable evils, and I lived in daily fear lest the monster whom I had created should perpetrate some new wickedness.

The Frankenstein story has been made into hundreds of movies and TV shows, and the basic plot has been borrowed thousands of more times than that, featuring robots, androids, cyborgs, and anything else that can spring from the human imagination.

Indeed, two centuries after Frankenstein, we all have our own examples of technology run amok, and each one, we can say, is simply the latest updating of Murphy’s Law; that is, anything that can go wrong, will go wrong.

So now back to the GAFA companies. They have been empowered, of course, by the miracle—or so it has seemed to many—of another Moore’s Law, the endless acceleration of digital computing power.

Who can resist the wonders of the Internet? Virtually no one; it’s the rare individual who is truly “off the grid.”

Thus today, the warning of Jack Williamson—that new technology would be so seductive that everybody wants in on it, even without understanding its risks—seems to be entirely unheeded.

Yes, we all know that the Internet is rife with abuse, and with the potential for even more abuse. Here, for example, is an August 7 Washington Post headline, “These 42 Disney apps are allegedly spying on your kids.” The story detailed allegations, filed in a federal lawsuit, that Disney has been secretly collecting personal information on its young customers and sharing that data illegally with advertisers. So yes, even a supposedly wholesome company such as Disney is fully in on the digital dark arts.

Yet even so, people of all ages are still becoming ever more “wired,” such that the stock-market value of the GAFA companies is today measured in the trillions—Apple’s capitalization alone is more than $900 billion.

To be sure, there are still some prophets alive today, offering warnings. One who sees the danger clearly is the controversial hacker-activist Julian Assange. In a speech to Cambridge University in 2011, Assange described the Internet as “the greatest spying machine the world has ever seen,” adding that the Net:

. . . is not a technology that favors freedom of speech. It is not a technology that favors human rights. It is not a technology that favors civil life. Rather it is a technology that can be used to set up a totalitarian spying regime, the likes of which we have never seen. [emphasis added]

Other informed observers have echoed Assange’s point. One such is Jonathan Taplin of the University of Southern California, author of the 2017 book, Move Fast and Break Things: How Facebook, Google, and Amazon Cornered Culture and Undermined Democracy. And yes, it’s available on Amazon; the tech companies seem to think they are beyond the reach of any critic. Still, Taplin keeps after them, saying recently that the techsters “are in the surveillance capitalism business. Their sole reason for being is to vacuum up as much data on two billion people as they can.”

And by now, of course, we’ve started to see where that can lead. Or can we? Interestingly, the human-powered tech companies of today are themselves hurtling into something even newer and more unknown: Artificial Intelligence (AI). We can recall that it was a fictional AI that formed the basis of the Terminator movies—in which a computer rebellion nearly exterminates humanity.

In the real world, plenty of informed observers—including the physicist Stephen Hawking and entrepreneurs Bill Gates and Elon Musk—think AI is a deadly threat. Indeed, in January 2015, hundreds of concerned experts co-signed an open letter, in which they warned:

We could one day lose control of AI systems via the rise of superintelligences that do not act in accordance with human wishes—and that such powerful systems would threaten humanity.

Yet interestingly, in the nearly three years since that warning, nothing has been done. To be sure, there’s been plenty of talk, but there’s been no regulation.

Admittedly, it’s far from certain that any regulation is even possible anymore, because legislators and regulators might never be able to police what’s being invented. Indeed, the anti-AI-ers are facing plenty of powerful pushback. For example, Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg, whose company already makes extensive use of AI, has dismissed the criticisms as “pretty irresponsible.”

In other words, for Facebook, it’s full speed ahead, and we have no idea what’s happening in the even more opaque companies and bureaucracies of China and Russia.

This is our scary world today: a little bit of the overt political tyranny of 1984, and a lot of the covert technological enticement of With Folded Hands.

So what’s going to happen to us? It’s impossible to know. The only thing we humans can say for sure is this: We were warned.

Next: When Warnings Prove True

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.