Gary Johnson, Hillary Clinton, or Donald Trump?

The latest CNN poll shows Donald Trump beating Hillary Clinton, 44:39. For Republicans, that’s good news. Of course, other polls show other results—some even have Hillary ahead.

Yet here’s something interesting about that CNN poll: It shows the Libertarian Party (LP) candidate, Gary Johnson, with nine percent. For LP enthusiasts, this must be a heady feeling; after all, since the LP first ran a candidate for president in 1972, the party has never gotten more than one percent of the November vote.

Yet history suggests that Johnson will end up a lot closer to one than to nine, even if Marvin Bush, brother of George W. and Jeb, has endorsed Johnson, and as rumors fly about the voting intentions of others in the Bush family.

Why the likely fade? Because support for third-party candidates has a way of eroding as they get closer to election day. That is, as voters start really to focus on the election, they make the cold calculation that one of the two major parties is going to win, and so they must decide: Which one of them do they prefer? Or, to put it another way, which major party is the lesser of two evils?

So it’s likely that Johnson’s nine percent rating will be whittled down in the months to come. And that means, of course, that libertarian voters will have to decide what they want to do. It’s hard to see any liberty-lover voting for Hillary Clinton, and so their three real choices are a) stick with Johnson, b) not vote at all, or c) vote for Donald Trump as the better of the two “majors.”

Interestingly, perhaps the best-known libertarian in the country, Peter Thiel—a past champion of everyone and everything from Rand Paul to seasteading—has made his choice: He has endorsed Trump. Not only that, but the the Silicon Valley mogul actually spoke on behalf of Trump at the Republican National Convention in Cleveland. And given the rapturous reception that Thiel received, it would appear that the GOP and Thiel-ish libertarians are a strong match.

So as we can see, libertarians—and fellow travelers in the Liberty Movement, such as Objectivists—are facing a fork in the road: Do they go with Johnson? Or with Thiel and Trump?

Theoretical Libertarianism and Applied Libertarianism

Here we can pause to draw a dichotomy within the Liberty Movement: We can call it the distinction between “Theoretical Libertarianism” and “Applied Libertarianism.”

Theoretical Libertarianism is what it sounds like—libertarian ideology, not connected to grubby politics. And Applied Libertarianism is what it sounds like—libertarian ideology that is connected to grubby politics.

We can quickly see that Theoretical Libertarianism appeals to those who seek purity, while Applied Libertarianism appeals to those who seek practicality.

And as we shall see, the theoretical and the applied can inhabit, at different times, the same person.

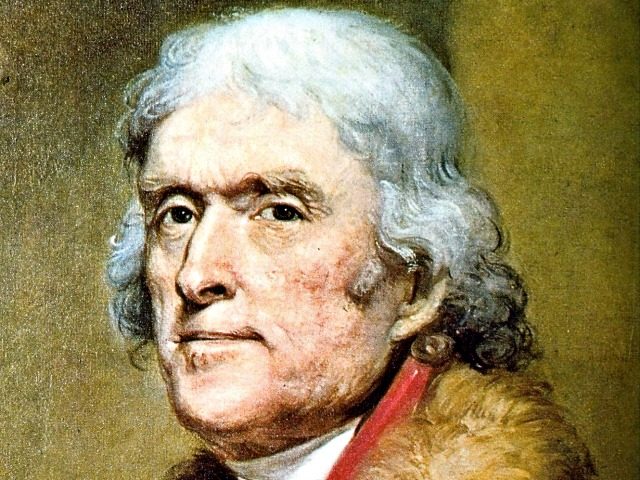

Thomas Jefferson: Theoretical Libertarian and Applied Libertarian

To illustrate the dichotomy, we can think back on the life of Thomas Jefferson, patron saint of American libertarianism.

Yet interestingly, Jefferson’s reputation as a libertarian icon is based mostly on the words and deeds in the first part of his long life—in the 1770s, 1780s, and early 1790s. In the first of those epochal decades, of course, Jefferson wrote the Declaration of Independence, which stands for all time as a milestone in human freedom.

Then, in 1781, Jefferson wrote Notes on the State of Virginia, articulating many key libertarian themes, such as, “Dependence begets subservience and venality, [and] suffocates the germ of virtue.”

Jefferson went on to extoll agricultural virtues, declaring, “Cultivators of the earth are the most virtuous and independent citizens.” Continuing in that vein, he added:

Those who labor in the earth are the chosen people of God, if ever He had a chosen people, whose breasts He has made His peculiar deposit for substantial and genuine virtue. It is the focus in which He keeps alive that sacred fire, which otherwise might escape from the face of the earth.

Rural life per se, to be sure, is neither pro- nor anti-freedom, but Jefferson had a libertarian point in mind. He feared that if people moved to the cities, they would lose their connection to subsistence, thus becoming a concentrated mass of wage slaves—and susceptible to demagoguery.

Indeed, in his libertarian thinking, Jefferson went even further. Sounding very Cato Institute-ish, he speculated that America, having not yet clinched its independence from Britain, might be better off without sea power:

Perhaps, to remove as much as possible the occasions of making war, it might be better for us to abandon the ocean altogether, that being the element whereon we shall be principally exposed to jostle with other nations.

Finally, in 1792, Jefferson, now serving as President Washington’s Secretary of State, had the pleasure of certifying that the Bill of Rights, which he had championed, had indeed been ratified into the Constitution.

Thus we have Jefferson the Theoretical Libertarian. Mostly sitting in his library in rural Virginia, as the busts of his heroes—Bacon, Locke, and Newton—gazed eyelessly down upon him, the Sage of Monticello was blessedly free to think any thought he might wish. And it is this Jefferson that is best remembered today; this is the Jefferson that inspires romantic libertarians on the left, as well as the right.

However, his outlook began to alter after 1801, when he was inaugurated as our third president. To be sure, his gut instincts hadn’t changed; in a famous passage from his first inaugural address in 1801, the new President declared that the national model should be minimal government and minimal government activity:

A wise and frugal Government, which shall restrain men from injuring one another, shall leave them otherwise free to regulate their own pursuits of industry and improvement, and shall not take from the mouth of labor the bread it has earned.

Yet even if his innate libertarianism was fully intact, as commander-in-chief he had to shoulder profound practical duties; hence, Applied Libertarianism.

Specifically, within a few months of his inauguration, Jefferson faced a genuine foreign threat, the Barbary Pirates. And that threat arose, not from a military intervention of the sort that libertarians deplore, but rather from the peaceful commerce that libertarians champion. In their avarice, the Barbary Pirates were eagerly preying on US merchantmen.

Thus it was that Jefferson, who had once mused about the advantages of not having a navy, undertook a major shift: Now practicing Applied Libertarianism, he launched the greatest overseas military operation that the US had ever seen, projecting American power all the way to the Mediterranean, “to the shores of Tripoli,” in the words of the Marine hymn. The conflict, lasting from 1801 to 1805, involved the fighting capabilities of some twenty US warships. And the result was an American victory, although it would take a second war, a decade later, finally to subdue the pirates and safeguard American shipping.

Meanwhile, President Jefferson was facing another test as well. Ominously, in 1801, Napoleon’s France had seized possession of the Louisiana Territory from Spain; that was a vast stretch of some 828,000 square miles, reaching from the Gulf of Mexico to the Canadian border. The French leader had even sent troops to reinforce his grip on New Orleans, potentially threatening the full range of Southern American states, perhaps the entire US. Jefferson knew that Napoleon’s forces had overrun much of the European continent; he had to wonder: Could they now do the same to North America? As he wrote in 1802:

France’s possessing herself of Louisiana is the embryo of a tornado which will burst on the countries on both sides of the Atlantic and involve in its effects their highest destinies.

The year after that, 1803, Jefferson undertook to solve the impending continental crisis in a creative and imaginative way: He bought out the French. Working through Robert R. Livingston, America’s Minister to France, he bought the entirety of the Louisiana Territory. Livingston was moved to exult, “The United States take rank this day among the first powers of the world.”

Meanwhile, back at the White House, Jefferson realized that the new territory had both to be explored and defended. So in 1804, he dispatched Meriwether Lewis and William Clark to survey the newly purchased territory, as well as the land extending all the way to the Pacific shore—more future American territory, Jefferson hoped. The expedition lasted two years, but when Lewis & Clark returned with their reports of the tantalizing bounty and plenty awaiting out west, observers agreed that the US needed a plan for actually traveling to it. The young republic had grown to 16 states, and the lands of the Louisiana Territory would ultimately be apportioned among 15 additional states. This new realm thus needed to be connected.

And so in 1806, Jefferson signed legislation to begin building the National Road. The first step on the Road was a 130-mile artery connecting the Potomac River at Cumberland, Maryland, to the Ohio River at Wheeling, Virginia (now West Virginia). Today, US 40 traces the path of the old National Road, from New Jersey to Utah.

In the meantime, Jefferson had also to think more about national defense. In 1802, he established the US Military Academy at West Point. After all, the fact that the French had sold the Louisiana Territory to us didn’t mean that they might not want to conquer it back. And at the same time, the British and Spanish were always on the prowl, and, on the Pacific Coast, the Russians loomed.

Then in 1808, Jefferson’s Treasury Secretary, Albert Gallatin, took another big step toward nation-building at home. Gallatin’s Report on Roads, Canals, Harbors, and Rivers argued for another national road, this one stretching from Maine to Georgia. In addition, he advocated new canals across the country, including, most presciently, a canal across New York State, linking the Hudson River to the Great Lakes—the future Erie Canal.

For his part, President Jefferson was still a libertarian, but as we have seen, the imperatives of statecraft impelled him to apply libertarianism in new ways. For him, the constant was the well-being of the American people: He knew that if they were safer and more prosperous, they were also likely to be more free.

After his presidency, Jefferson returned to his beloved Monticello. From that vantage point, he continued to churn out a vast correspondence, reminding us nevertheless that at his core, he was still a Theoretical Libertarian.

Thus we see that it’s possible to be both a Theoretical Libertarian and an Applied Libertarian, albeit at different times, according to the exigencies of circumstance.

To Be, or Not To Be, a Republican?

So now to the present: We can quickly see that Gary Johnson is a strong proponent of Theoretical Libertarianism. A look at his campaign website, for example, confirms this point: On immigration, he is for open borders; as he puts it, “A robust flow of labor, regulated not by politics, but by the marketplace, is essential.” And what about the threat of terrorism? After all, the Tsarnaev Brothers, aka the Boston Marathon bombers, came here in 2004, and Tashfeen Malik, one of the San Bernardino shooters, came here in 2014. And in France and Germany, of course, the situation is even worse; it seems like every day now, there’s an attack. Here’s Johnson’s answer to those concerns:

Making it simpler and efficient to enter the U.S. legally will provide the greatest security possible, allowing law enforcement to focus its time and resources on the criminals and bad actors who are, in reality, a relatively small portion of those who are today entering the country illegally.

If that answer strikes you as sufficient to the challenge posed by ISIS and jihad, then, well, you’re probably a Theoretical Libertarian—or a Democrat.

Yet in the meantime, Applied Libertarians, such as Thiel, are supporting Trump. Trump himself might not be a libertarian, but he is certainly a capitalist, and as all libertarians know, capitalism expands freedom.

Indeed, there’s a long tradition of Applied Libertarianism merging into Republican politics and policymaking. The late William F. Buckley was basically a libertarian, but to his mind, the overriding need to repel the advance of the Soviet Union required him to throw in with the Republican Party.

And Alan Greenspan was an early associate of Ayn Rand and a follower of her Objectivist philosophy, which is akin to libertarianism; later, of course, Greenspan was appointed to senior economic posts in the Nixon and Reagan administrations. And speaking of Objectivism, House Speaker Paul Ryan has credited Atlas Shrugged, and other Rand writings, with helping to shape his worldview.

Moreover, my old boss in the Reagan White House policy development office, the late Martin C. Anderson, was a hardcore libertarian, albeit one with a practical streak. After he left the Reagan administration, Marty went on to write Revolution: The Reagan Legacy, an admiring chronicle of the Reagan years. Till the day he died, Marty never stopped believing in freedom, but he also believed in getting things done.

Indeed, since probably 90 percent of Republican economists are not conservative at all, but, rather, libertarian, it’s safe to say that many other GOP brains have made the same Greenspan/Anderson calculation—the same calculation that Jefferson once made: in a crunch, the practical preempts the theoretical.

So each of us must make our choice—purity or practicality.

And speaking of practicality, here’s a point that ambitious libertarians might keep in mind: Trump is strong in the polls; according to analyst Nate Silver, he now has a 49.1 percent likelihood of winning—although his “win likelihood” percentage has been as high as 57.5. Yes, the election is that close.

If Trump wins, then Peter Thiel is in a good place; he will have made another smart bet, and will have an open door in Washington, DC, for his ideas. But for Gary Johnson and his allies—there’s not much to look forward to, in terms of practical outcomes. Again, that’s the difference between Applied and Theoretical.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.