The old adage that “winners write history” is mostly untrue; historians write history. The way future generations view the past often comes through the myriad of complex and biased accounts of those who bothered to record it. In Lincoln’s Boys: John Hay, John Nicolay and the War for Lincoln’s Image, historian Joshua Zeitz explains how Abraham Lincoln’s two secretaries rescued and perpetuated Abraham Lincoln’s image as the “Great Emancipator” and the man who saved the Union.

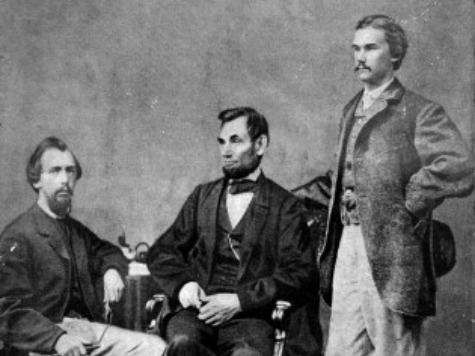

John Hay and John George Nicolay established Lincoln’s legacy by writing a brilliant and masterful 10 volume biography, Abraham Lincoln: A History, which secured Lincoln’s reputation in history and gave other writers a springboard off of which to base their own accounts.

Hay, who was born in Salem, Indiana, not only served as Lincoln’s secretary but also became a prominent statesman himself. He served as secretary of state under Presidents William McKinley and Theodore Roosevelt and had an extensive career in politics. He knew almost every prominent American figure in the late nineteenth century, helped craft the Open Door Policy with China, and signed the treaty to begin construction of the Panama Canal. It was also Hay that famously quipped that the Spanish-American War was a “splendid little war.” Hay’s life was the topic of another recent biography, All the Great Prizes: The Life of John Hay, from Lincoln to Roosevelt by James Taliaferro, and deserves higher recognition from Americans today.

Nicolay was a Bavarian-born journalist who supported Lincoln when Lincoln ran for the U.S. Senate against Stephen A. Douglas. He later also served as Lincoln’s secretary during the war. Nicolay and Hay together acted in the capacity of a modern chief-of-staff, dealing with office seekers and those who wanted access to the president. During Lincoln’s presidency they worked 80 hours a week at Lincoln’s side with very few chances to rest. During that time, they became intimately familiar with the president’s abilities and the cause that he lead. Few men in America were in a better position to tell Lincoln’s tale from a perspective that the 16th president would have recognized.

Zeitz’s narrative focuses on the relationship Hay and Nicolay had with Lincoln, but goes beyond just recounting the events of the Civil War. It explains how Hay and Nicolay embraced a newly-formed Republican Party, stood by the side of its greatest champion in his darkest hours of the bloodiest war in American history, and then fought to defend that legacy for the rest of their lives.

He also explains how Lincoln was perceived by the American people, and how that perception often differed from the crowd in Washington, D.C.

Zeitz wrote that Lincoln never translated his popularity to the nation’s “political and intellectual elites.” He wrote that “the profound emotional bond that he shared with the Union soldiers and their families, and his stunning success in two successive elections, never caught on with the “men who governed the country and guarded its official history.” In many ways this is similar to the wide gap between how the American people and history professors view Ronald Reagan.

Zeitz noted that Nicolay and Hay saw Lincoln as “steadfast where other men wavered; he saw the long game, where others staggered from crisis to crisis.” Zeitz wrote that “Americans today understand Abraham Lincoln much as Nicolay and Hay hoped they would” because of their impressive historical work.

After the war, a number of historians tried to diminish Lincoln’s accomplishments, attributing his success to able cabinet members and portraying him as a good but simple man who was out of his depth.

When Hay heard a particularly negative account of Lincoln by legendary historian–and partisan Democrat–George Bancroft, he blasted the address as a “disgraceful exhibition of ignorance and prejudice.”

Hay believed that Lincoln was “Republicanism incarnate, with all its faults and virtues. As in spite of some evidences, Republicanism is the sole hope of a sick world, so Lincoln, with all his foibles, is the greatest character since Christ.”

Nicolay and Hay undoubtedly gave posterity a Northern, partisan account of Lincoln and the war. This was in part due to the rising flood of writing from the “Southern” perspective and because they were at the heart of the ideological conflicts that sparked the war, from which they ultimately were unable to detach themselves.

For instance, Nicolay essentially called Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee a “liar” for his actions and decision to leave the Union army, while praising Union Gen. Winfield Scott who was also a native Virginian. He believed Lee should have been shot for treason, but this was left out of the books.

Hay took aim at legendary and beloved Southern hero Gen. Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson, calling him a “howling crank.” Though recognizing some of Stonewall’s battlefield greatness, Hay blasted him as being a “slow, dull, unprepossessing youth” who “had the war not come to call him forth to glory and the grave… would probably have lived and died in the mountain village known only to his neighbors… ‘as a sincere, odd, weak man.'”

It is hard to imagine Lincoln, who said “with malice toward none, with charity for all” in his second inaugural address, and who played the beloved Southern song “Dixie” in front of the White House at the war’s close, expressing these sentiments.

Lincoln’s Boys does a fantastic job in bringing Nicolay and Hay back from historical obscurity and an even better job of demonstrating how historians, even “non-professional” ones, can shape the popular perception of events. It offers a glimpse into how nineteenth-century Americans came to grips and tried to explain the great war that almost extinguished their civilization.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.