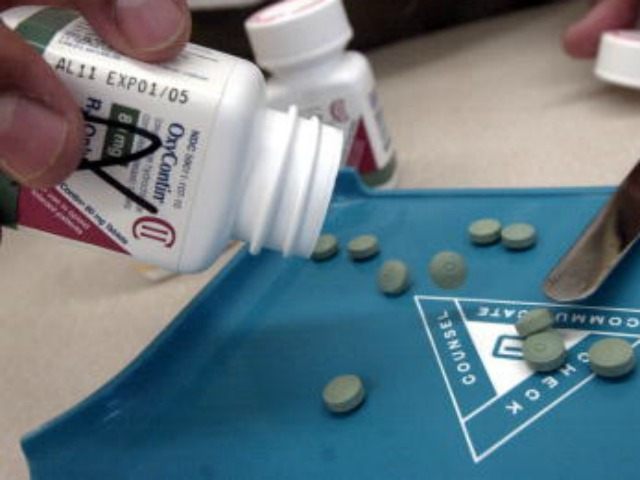

On the campaign trail in New Hampshire, presidential candidate Jeb Bush spoke about the dangers of an over-medicated society, noting ruefully that 90 percent of painkiller prescriptions worldwide are coming from America.

When he moved to the subject of the FDA approving a version of OxyContin for children, he delivered an entirely accurate statement that could nevertheless become an unfortunate sound bite.

“This is not appropriate,” Bush said of the pediatric Oxy. “We have to take a pause and recognize that pain is part of life. You have to monitor pain and deal with it. But overprescribing creates all sorts of adverse problems as well.”

Bush later elaborated on his point about Americans over-medicating. “The gateway drug isn’t marijuana anymore,” he said. “Prescription drugs… we’re way over-prescribing as a nation, and that creates big hardship for families. There needs to be a dialogue about that.”

“Pain is part of life” is not what the culture of 2015 wants to hear, and it’s bound to raise sarcastic chuckles as the impromptu slogan of Bush’s presidential campaign… but he’s right, and the quest to avoid pain has gone far beyond the point of diminishing returns. This is true of every form of discomfort – from physical and emotional pain, to economic anxiety and the “trigger words” culture of hyper-sensitivity on campus.

Bush spoke about over-reliance on prescription painkillers at the very moment studies of rising middle-age mortality, especially among white middle-class Americans, is making headlines. A tremendous increase in patient complaints about chronic pain, met by the surge in medication Bush described, is thought to be a major factor behind these deaths. Bush’s rival Chris Christie also spoke about the dangers of middle-age painkiller addiction in New Hampshire this week.

We under-estimate the dangers of addiction at our peril. Even people who believe they have strong will, healthy bodies, and purposeful lives can become addicted to relatively mild medications. Our medical system is not always good at spotting the signs of addiction. It’s much too easy for patients to assemble a smorgasbord of drugs from different doctors.

Conversely, patients who think they can handle their dependencies are slow to admit they have a problem or seek serious treatment. Getting away from pills is one of those challenges that is much harder than we like to admit… the sort of challenge often put off until a tomorrow that never comes.

Middle-aged people leading middle-class lives incorrectly, but understandably, believe that admitting to a dependency problem will be seen as a deficiency of character. When they’re already anxious about their careers, financial future, and family relationships, they feel as if undergoing treatment for a drug problem could be a burden their already fragile lives would not survive.

This time of middle-age, middle-class despair isn’t just about drugs, however. It’s a social and cultural problem as well.

The UK Telegraph filed a dispatch earlier this year from a resort in Arizona filled with men of the “sandwich generation,” caught between the Baby Boomers and digital youth. The younger members of this cohort are the adult versions of Generation Xers who thought much of life was hypocritical or futile when they were in high school, grown into the world they feared was waiting for them.

The Sandwich Generation includes a high number of divorced and never-married men who had no idea what to do with their lives. Some are disoriented from the relentless assault on masculinity, left with a vague sense they’re supposed to be like their “silent, strong, and austere fathers who went to work and provided for their families,” but aware modern society puts a higher value on “progressive, open, and individualistic” youth, to borrow the words of a professor researching suicidal behavior who was quoted by the Telegraph.

“We married capable women who took over every aspect of life,” explained a 50-year-old friend of Telegraph writer Lucy Cavendish.

They ran the household, the children, the social life. For a while it seems a good meal ticket to be on, but in the end the horrible logic of the process results in us being without any kind of a role at all and not much self-confidence to find another one within the existing framework. We are caught between the old model of being the breadwinner and the new model of being the co-washer-upper and feeder, and the truth is we never really mastered either of these roles – old or new – and this has led to a profound sense of crisis in men.

Are the expectations of middle-age men cultural constructs, or wired into their biology? The difficulty so many American men have in dealing with contemporary disappointments suggests male identity runs deep, and it’s far too early to assume that young men of the digital generation won’t have similar problems when they hit their forties, if the same social conditions persist.

Establishing a family homestead, bringing a solid marriage gracefully into the golden years, guiding children into the adult world of higher education and employment… these are characteristics of an imperiled “American dream” that might be better understood as what mature men feel, in their hearts, they’re supposed to be doing. If it’s more than just a vestigial cultural memory of what the men of previous generations were working on as they approached the Big Five-Oh, this sense of despair will not soon evaporate.

Women are seen as much better able to cope with these pressures, thanks to empathy and their support networks of close friends. They’re also spared from much of the social and political artillery fire targeted at re-defining or erasing masculinity. It’s no coincidence that campus culture for the past few decades has been obsessed with defeating “patriarchy.” They’re getting what they wanted, and the would-be patriarchs are arriving at middle age to find themselves in a bombed-out cultural battlefield.

But women are not completely immune to the rising tide of middle-age despair. They bear a heavy burden from divorce culture, especially as people wait until later in life to have children, leaving a noticeably older cohort of women to raise children after marriages collapse, or become never-married single moms.

Both men and women find themselves bereft of the communal and spiritual resources provided by organized religion, which continues to wane. A new Pew Research Center study found a growing minority of Americans, particularly young people, describing themselves as religious or spiritual but “unaffiliated” – that is, they belong to no organized faith, and therefore do not attend services. Whatever else one may say about this religious identity, it lacks, by definition, the social connections an organized religion supplies. There is no religious community, no church social events, no networking with fellow believers, no counseling from supportive clergy. Those old-fashioned organized religious have an arsenal of powerful weapons against despair.

Culturally, the middle-aged, middle-class white male finds himself an object of disdain from many directions. He is portrayed as an unfairly “privileged” creature who has no right to complain about anything. All of society’s problems are laid at his feet. He is judged collectively guilty of numerous crimes: racism, sexism, cruelty, intolerance…

It’s not exactly chicken soup for the soul when men who arrive in middle age feeling uncertain about their place in the world, and anxious about the future, are lectured that literally everyone else is worse off than they are, because white-guy-dominated society is inherently unfair to every other group.

Men and women of middle age both suffer from economic anxiety, in a world of mounting debt, uncertain long-term prospects, and a collapsing workforce. The loss of career positions leaves older workers at a disadvantage, as it reduces the value of their accumulated experience. Career tracks that end with decent retirement benefits are becoming harder to find. Dependency on government has been pushed further and further into the middle class, making people with quite comfortable incomes dependent on taxpayer subsidies for goods such as health care. Those in the upper middle class targeted as revenue sources to pay for all this dependency find themselves viewed with spite and suspicion, not gratitude. Frankly, they’re beginning to feel like chumps for lifetimes of working hard and playing by the rules.

We have become a society averse to every sort of pain, holding up a life free of distress – even the incredibly mild distress of hearing words that might be construed as offensive – as the highest ideal. Aversion to pain easily becomes an aversion to responsibility, and the devaluation of achievement, because very little worthwhile is achieved without suffering. Despair can be defined as the absence of achievement and purpose – no sense of accomplishment looking back, no eager anticipation looking forward.

The issues of prescription drug addiction and physical pain, difficult as they are, may prove to be more straightforward challenges than addressing the other factors driving middle-age mortality. It is very difficult for a man to grow old in a world that no longer needs his father.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.