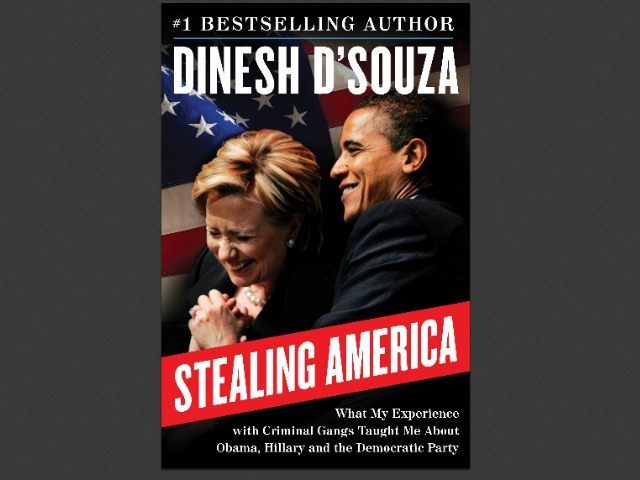

Editor’s Note: The following is part 3 of 3 exclusive Breitbart News excerpts from bestselling author Dinesh D’Souza’s new book, Stealing America: What My Experience with Criminal Gangs Taught Me about Obama, Hillary, and the Democratic Party. Read part 1 here, and part 2 here.

Then Brafman exposed the government’s below-the-belt tactics.

Brafman’s proof was contained in his written reply to the government’s sentencing brief. This document, now available online, methodically exposed the prosecution’s deception. It had two side-by-side columns, one listing the facts reported by the government in the cases it cited, and another listing the facts left out. These were not omissions by over- sight, Brafman noted; the government had deliberately slanted its case summaries to deceive the judge into thinking that prison time was normal for this kind of offense. Moreover, the government had delib- erately ignored cases that did not result in prison sentences.

Brafman said, “The zeal with which this case was brought from in- ception to the Southern District is uncharacteristic of any case that we have found.” He added, “In this case things happened in this prosecu- tion that are not ordinary.” The government, for instance, refused to give me the normal two points of credit for pleading guilty. “Judge,” Brafman said, “I have never had that happen in any case in thirty-seven years. I have never had a defendant who actually pled on the eve of trial lose his two points.” Reluctantly, Brafman said he had come to the con- clusion that I was being selectively prosecuted, not for what I did, but because of who I am. Brafman noted that I had long felt that way, and “in this case I think he’s right.”

Brafman concluded by making it clear to the judge that a prison sentence would be so out of the ordinary that it would cast suspicion on the judge’s own fair-mindedness and place him squarely in the camp of the get-this-man-at-any-cost prosecution. He concluded, “There is not a single case anywhere in the United States of America that either I or the government with all of their resources have found where someone like Mr. D’Souza, who is a first offender, who is not an attorney, who is not a campaign official, who had no corrupt relationship with the can- didate, who has given twenty thousand dollars through straw donors, has gone to prison.” Indeed, “We cite in our memo a dozen cases far worse than the defendant’s and all of the judges in all of those cases throughout the country imposed a nonprison sentence.”

Brafman finally sat down. He had completed his tour de force; he was spent. Now it was out of his hands. I looked over at the clerks, who were staring, openmouthed, at Brafman. Their ennui was gone; they were totally riveted. The judge rubbed his chin, and then said some- thing very strange. He made the observation that, from his point of view, there was no real disagreement; he and Brafman had basically said the same thing. “Everything that you have said and everything that I have said,” the judge exclaimed, “has totally overlapped.”

Brafman’s face registered his amazement. Everyone in the court was incredulous. The two men were at opposite poles, the one impassioned in blasting me, the other impassioned in defending me, and yet here was Judge Berman professing his inability to tell the difference. Was he playing some sort of game? Was this the Twilight Zone?

The judge then turned to me. “Mr. D’Souza?” I had prepared a short statement to read, but decided on the spur of the moment to directly address the issue that seemed to have baffled the judge most about me. “Your Honor,” I said, “I would like to try to answer the question you raised as something that has been disturbing and puzzling you about what’s going on here, why would somebody like me do a thing like this.” When I began to speak I saw Brafman’s surprise—naturally he expected me to read my prepared statement—and the judge inter- rupted me. “Explain to me why you—you—are here and why you did what you did. Not somebody like me, some famous person, blah, blah blah.”

I was not off to a good start. “Okay,” I said, attempting to regroup. “I was seventeen years old when I set foot in America. I came as an exchange student from India. I grew up in a very settled community. Most of my relatives lived within a one-mile radius of where I lived. I didn’t realize when I came here that I was actually never going home. In other words, I came here for a one-year program, after which I ex- pected I would return home. But I stayed in America. America opened up doors of opportunity for me—I found myself a student at Dart- mouth.

“The experience of leaving one’s country is a little terrifying, be- cause you leave everything that matters to you behind, your family, your friends, everybody you know. And you are insecure in many dif-ferent ways, financially insecure, emotionally insecure. In some senses, you are insecure in your identity. Because you leave your old country, in some ways you are no longer Indian, and yet you begin to wonder if you’ll ever be American. You are walking a tightrope between two buildings, and you feel in no-man’s-land, somewhere caught in be- tween.

“When I was at Dartmouth, I found a group of friends who wel- comed me in. I became part of that group. You can say that they became my American surrogate family. I say that because at that time, in four years of college, I never went home. I had no money. So I ba- sically earned my way here in America, and these became my close- knit friends who literally took me for the first time to a store to buy a navy-blue blazer, explained to me that that’s part of the etiquette of being a Dartmouth student. And so the very basic assimilation to American life was accomplished by a group of close friends that I met basically between the time I was eighteen and twenty.

“Wendy Long was one member of that group of four or five people. So even though over the years we have lived in different places, dif- ferent states, there is a certain kind of amalgam of hearts that occurs because of that. You feel very close to that person, and you care about them in a very fundamental way, not differently than you care about your family.”

So that, I said, is why I went overboard in trying to help Wendy. I also wanted to address the judge’s apparent concern that I was not contrite over my misdeeds. “I am not shy,” I said. “I have not been reluctant to express my views in public. And I have done that for twenty-five years. It’s not like I started doing that when this case began. I have been doing that for my whole career. There is no inconsistency in saying I disagree with the Obama administration. I think a lot of the things they are doing are wrong. There is no inconsistency with me saying that and saying at the same time I did something wrong, which I regret. I wish I never did it, and I will never do it again.”

I urged the judge to give me a fair sentence, which I said was not a prison sentence. Then I sat down. I turned back to look at my friends in the audience. They had tears in their eyes, tears of concern for my fate. I also saw that Adelle Nazarian of Breitbart News was weeping. As an immigrant, she felt for me. I looked over at Judge Berman’s clerks. Their catatonic boredom was long gone; they were completely mesmer- ized by what was happening in the courtroom. Judge Berman took a short recess, one of the most suspenseful intervals in my life.

When he returned he began by saying, “I don’t think that it’s nec- essary for Mr. D’Souza to go to jail.” Just those words. A wave of relief came over me, although I tried to conceal it. I had steeled myself not to show expression even if I got two years. I didn’t want to give my ill-wishers the relish of it. So I registered a blank expression, even though inwardly I was elated. Brafman, however, could not have been more delighted. His face darted from side to side, his eyes gleaming, as if to say, “Did you see me pull that off?”

Later, when I emailed Brafman to thank him for his stellar work on my behalf, he replied, “This was one of my finest moments in thirty-eight years of work and I am absolutely delighted that I was able to save you from prison. It is a badge of honor I will display proudly for the rest of my life.” He added, “I will also have great joy in the out- standing success you will no doubt achieve in the years ahead. Indeed, having fought the government and prevailed will no doubt make you even more of a hero than you already are to so many, including me.”

Having announced that he would not send me to prison, Judge Berman proceeded to hand down his sentence. I was given eight months of overnight confinement in a halfway house. I had to do one day a week of community service teaching English to new immi- grants, as well as one hour of psychological counseling. I had to pay a $30,000 fine. I also got five years probation. Significantly, the judge said he could not require me to pay restitution since my offense had not harmed anybody.

What happened that day in the courtroom? I would spend many hours reflecting on that subject, as well as discussing it with Brafman, with others who were present in the courtroom, and with friends who are lawyers and political observers. One view is that Judge Berman never intended to give me prison time; he recognized how absurd that would be for what I did. He did want to make me sweat, however, and that accounts for the tongue-lashing he administered at the outset.

A second view, which I share, is that Judge Berman initially planned to give me prison time but was largely swayed by Ben Brafman. Either way, one thing was clear: the judge did not go along with the government’s position. He refused to be the government’s pawn and participate in its transparent public deception.

Therein lay my victory. Judge Berman had given me a harsh sen- tence, out of proportion to what I did. He was forcing me to sleep every night in a confinement facility for eight months. He was dispatching me to psychological counseling, which, while not onerous, is odd for a case like this. After all, I had not done something bizarre like store bodies in my refrigerator; was my offense really one that required me to have my head examined? When I figure my legal fees plus the court-imposed fine plus the confinement center assessment, the case has cost me over half a million dollars.

If you have any doubt that my sentence was severe, compare my case to that of Sant Singh Chatwal, hotelier, fellow Asian Indian, and Democratic fundraiser. In 2012, Chatwal pleaded guilty to making more than $180,000 in straw donations to several Democratic candi- dates, including Hillary Clinton. In fact, Chatwal was the founder of “Indian Americans for Hillary 2008.” Chatwal also pleaded to witness tampering; the FBI recorded him instructing a government witness to lie under oath. Chatwal was clearly trying to buy influence; indeed, he had publicly stated of politicians, “When they are in need of money, the money you give, then they are always for you. That’s the only way to buy them.” Chatwal received a fine, community service, and three years probation. No prison time, no confinement. In sum, for doing something vastly worse than what I did, he got a vastly lesser penalty.

I didn’t know about the Chatwal case when I was sentenced. But even had I known, it would not have killed my enthusiasm. That day, I was jubilant. Why? Because I recognized that the government—by which I mean the Obama administration—had lost. Success for them meant discrediting me, destroying my career. This had already failed, since my supporters were savvy enough, even without knowing all the details, to know what was up. The government’s only hope at this point was to send me to prison, to put me away, ideally for a long enough time that I could not make a movie in the 2016 election year. Had I re- ceived a year or more in prison, I would not in fact be able to do that. But now I could. Moreover, the left had intended my incarceration to be a propaganda victory, and now they could say goodbye to all that.

The prosecutor, Carrie Cohen, looked crushed as she left the court- room. She avoided looking at me. Politically, she knew that I had won, and she also knew I knew. Pretty soon she would have to tell Bharara, who would probably recognize instantly that he was not going to suc- ceed Eric Holder. And he would have to tell Holder, who would have to tell Obama. None of these thugs-in-power would be happy to hear the news! As I left the courtroom, my smile reflected the fact that all these scenarios were moving quickly through my mind.

That night, I could barely stop grinning as I discussed my sentence on the Fox News Channel’s The Kelly File. I told Megyn Kelly that the government tried to put me away, but a federal judge refused to let them. “This is a big political win for me,” I confessed. And the system worked; the sentence, albeit severe, had confirmed my faith in Amer- ica. Megyn was incredulous. “Only you, Dinesh,” she said, would use the occasion of a rather harsh sentence to reaffirm your love of country. After all, I was headed to a confinement center! I told Megyn not to worry; by the time I left, all those people would be Republicans! When the show was over, Megyn flung her arms around me and hugged me.

Shortly after my sentence, Eric Holder announced his resignation. I waited to see if Obama would appoint Preet Bharara to the job. He did not. Instead he appointed Loretta Lynch, U.S. attorney for the Eastern District of New York. I believe the message was: sorry, Preet, but you didn’t come through for us, and now we’re not going to come through for you. Our ambitious Indian water-carrier will have to wait a bit longer for someone to reward him for his henchman services.

I had won—for now. But I knew I still had an ordeal ahead. I had no way of knowing what was in store for me at the confinement center. Let me just say that it was not overpopulated with dentists, entrepre- neurs, and CEOs. Rather, I was destined to spend every night for the next eight months sleeping in a dormitory with more than a hundred rapists, armed robbers, drug smugglers, and murderers. It would turn out to be one of the most eerie, and formative, experiences of my life.

Here, among the hoodlums, I learned how to see in the dark, and through this “night vision” I began to see politics very differently. I got to know the hoodlums and read some of their case files. I learned how they think and how they operate, how they organize themselves into gangs, how they rip people off and crush their enemies. I understood, for the first time, the psychology of crookedness. Suddenly I had an epiphany: this system of larceny, corruption, and terror that I encoun- tered firsthand in the confinement center is exactly the same system that has been adopted and perfected by modern progressivism and the Democratic Party.

This book is an exposé of Obama, Hillary, and modern liberalism not as a defective movement of ideas, but as a crime syndicate. And I have to thank Obama, the liberals, and the judge for this learning opportunity. All of them are responsible for putting me in a situation that made this book possible. All of them wanted to teach me a lesson. And I can now say, with the benefit of hindsight, that their objective has been met. Little did they know what a valuable lesson it would be, even if not quite the lesson they intended.

From STEALING AMERICA by Dinesh D’Souza. Copyright © 2015 by Dinesh D’Souza. Reprinted courtesy of Broadside Books, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.