With the Iowa Caucus just days away, pundits, observers, voters and campaigns are poring through every new poll, hoping to divine a winner.

History, however, suggests a healthy dose of caution when trying to project the outcome from polls of Iowa. Not only are they bad at picking winners, they often miss late breaking shifts, and even waves, in voters’ attitudes.

During the Republican nomination contest in 2012, there were 8 public polls in the final week of the campaign that were included in RealClearPolitics average of polls. Five of these gave the edge to Mitt Romney, 2 predicted Ron Paul would win and one poll had a tie between Romney and Paul.

In the end, former Pennsylvania Sen. Rick Santorum won the Caucus, just edging out Mitt Romney. Ron Paul came in third. The more surprising fact though, was that, in all the polling, Santorum was a very distant third or fourth in the month before voting. His final vote share on caucus night was 8 points higher than predicted in the final polling. In other words, the polls underestimated his final vote by around 40 percent.

In the 2008 Republican contest, the polls were better at picking the eventual winner, but widely missed the margin of victory. There were 15 public polls the week before the caucus. Former Arkansas Gov. Mike Huckabee led in 11 of these while Mitt Romney led in 4. Except for one of these polls, which showed Romney ahead by 9 points, all of the leads in these polls were within the margin of error.

The polls predicted a very close race, with a slight edge to Huckabee. He ended up winning in a rout, however. Huckabee won the race by 9 points and racked up more total votes than ever received by a Republican candidate in the Caucus.

One common denominator in both 2008 and 2012 is that the victor in each contest received heavy support from evangelical voters. Santorum’s vote, as noted, was 8 points higher than predicted. Huckabee’s was almost 7 points higher than predicted. It is very likely that polling in Iowa underestimates the size or intensity of the evangelical vote.

That isn’t the only problem with polling in Iowa, however. Recent Democrat caucuses have been equally difficult to poll accurately. In the 2008, there were 15 public polls of the Democrat contest the week before the caucus. In 7 of these, Hillary Clinton led Barack Obama and John Edwards. Barack Obama led in 4, while John Edwards led in one poll. Clinton and Obama were tied in one poll, while in another Obama and Edwards were tied.

One poll, released the day before caucus even showed Hillary Clinton winning the contest by 9 points. In the end, Obama won by almost 8 points while Clinton finished third. Obama, the victor, outperformed the polls by 8 points, almost the same margin that Huckabee and Santorum had outperformed their poll projections.

Polling was more limited in the 2004 Democrat contest, but just a few days before the caucus, the polls were predicting a Howard Dean victory. John Kerry was in a three-way tie for second with John Edwards and Dick Gephardt. Kerry ended up winning with almost 40 percent of the vote, beating second place Edwards by 6 points. Dean finished third, almost 20 points behind Kerry. Dick Gephardt, who ran a strong second place in much of the polling in the weeks before the caucus, was fourth with just 10 percent of the vote.

It bears repeating that caucuses operate very differently than primaries, which likely makes polling so difficult. Unlike primaries, caucus voters have to show up at a specific time and place to participate. There is no absentee or early voting. Participating in a caucus also can take an hour or more, whereas voting in primaries takes minutes.

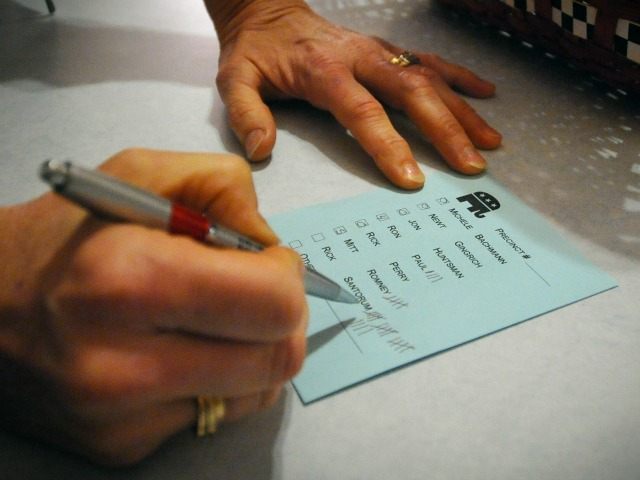

In addition, before voting takes place, a representative from each campaign can make a final pitch to caucus-goers before they vote. This happens in each of the thousands of voting places across the state. The quality of this pitch, and the person identified to make it, can have a dramatic impact on the outcome of the voting, especially in the Democrat vote. Democrat caucus-goers publicly declare their vote, while Republicans vote in a kind of secret ballot.

There is another important note to keep in mind that could perhaps become relevant this year. This first vote is just the beginning of the full caucus process. Although Ron Paul finished third in the Caucus in 2012, he actually ended up with more delegates than either Romney or Santorum. Delegates are not awarded in the initial vote to select the “winner” of the caucus, but through a process that begins after that initial vote. The short explanation is that Paul’s voters were organized and stayed at the caucus for that process, while voters for the other candidates left before that process began.

Organization and a highly effective ground game are perhaps more critical in Iowa than any other state that votes in the nomination contest. Not only do voters have to be turned out at a specific time, but they need to be educated on a very unique voting process. Moreover, someone has to be identified to represent the campaign in every precinct. Finally, a campaign’s supporters have to be instructed to remain after the “headline” vote to participate in the process that ultimately selects the delegates.

Polling is one important barometer in the state of any campaign. In Iowa, especially, it is simply one data point to assess. To get a feel for how the Iowa caucus will turn out, pay a little less attention to polls and a lot more attention to the campaigns’ organization and ground game.

Building a field of dreams and hoping “they will come” only works in the movies.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.