“Many passages in President Roosevelt’s book could have been written by a National Socialist. One can assume he feels considerable affinity with the National Socialist philosophy.”

–Nazi newspaper Volkischer Beobachter review of FDR’s book Looking Forward

At a time when the left and the media routinely liken President Trump and the Republicans to fascism, it is time to report on a little secret history that has been nicely buried by progressive historiography. Normally history cannot be so easily tucked away, but in this case, the left is so dominant in academia and the media that it has been able to get away with it.

The reason for the concealment project is to cover up the sins of the progressive icon Franklin Roosevelt and of American progressivism more generally. What’s reported here—the left’s early romance with fascism and national socialism—is a major embarrassment for the future prospects of the left. How can the left claim to be the party of “progress” and all things good, true and beautiful when the record shows the left was in bed with Mussolini and, to a lesser extent, Hitler?

In this article, I examine President Franklin Roosevelt’s enthusiasm for Mussolini, which was not unique to him but represented a larger movement of American progressives who looked to Italian fascism as a model for America. Some on the left even looked for leadership to Hitler. And the enthusiasm was reciprocal: both Hitler and Mussolini praised FDR and saw in the progressive New Deal an at least partial realization of the ideals of both fascism and National Socialism. Let’s peek into the windows of this mutual admiration society.

It should be said at the outset that FDR personally had no affection for the Fuhrer. But he did for Mussolini. In a letter to journalist John Lawrence, a Mussolini admirer, FDR confessed, “I don’t mind telling you in confidence that I am keeping in fairly close touch with that admirable Italian gentleman.”

In June 1933, FDR wrote his Italian ambassador Breckinridge Long—another Mussolini admirer—regarding the fascist despot. “There seems no question he is really interested in what we are doing and I am much interested and deeply impressed by what he has accomplished and by his evidenced honest purpose in restoring Italy.”

From FDR’s point of view, Mussolini had gotten an earlier start in expanding state power in a way that FDR himself intended; Italy under the Duce seemed to have moved further down the progressive road than America. So FDR urged leading members of his brain trust to visit Italy and study Mussolini’s fascist policies to see which of them could be integrated into the New Deal.

Rexford Tugwell, one of FDR’s closest advisers, returned from Italy with the observation that “Mussolini certainly has the same people opposed to him as FDR has.” Even so, “he seems to have made enormous progress.” Tugwell was especially impressed by how the Italian fascists were able to override political and press opposition and get things done.

Tugwell quoted favorably from the 1927 charter of Italian fascism, the Carta del Lavoro, which seems to have impressed him far more than the American Constitution. Fascism, he concluded, “is the cleanest, neatest, most efficiently operating piece of social machinery I’ve ever seen. It makes me envious.”

This sycophantic devotion to fascism, strange though it appears today, was at the time characteristic of the way that leading leftists felt about Mussolini, both in Europe and the United States. In England, the Fabian socialist George Bernard Shaw praised Mussolini for actually implementing socialist ideals. In 1932, the utopian leftist novelist H. G. Wells actually called for a “liberal fascism” in the West, emphasizing the need for “enlightened Nazis.” As for the novelist Gertrude Stein, she insisted as late as 1937 that the most deserving candidate for the Nobel Peace Prize was Adolf Hitler.

The American left was just as crazy as FDR and his crew about Italian fascism. The leftist journalist Ida Tarbell interviewed Mussolini in 1926 for McCall’s magazine and returned effusive with praise. Leftist muckraker Lincoln Steffens, who famously said of the Soviet Union, “I have seen the future and it works,” also praised Mussolini for his leftist sympathies, noting rapturously that “God has formed Mussolini out of the rib of Italy.”

Progressive writer Horace Kallen, an early champion of multiculturalism, said it was a “great mistake” to judge fascism as merely tyrannical, noting it was an experiment in social justice “not unlike the Communist revolution.” Both systems, he said, had given citizens a sense of unity and we should approach them with patience, and judge them only by their results.

For progressive historian Charles Beard—known for his attacks on the American founders as selfish landed capitalists—Mussolini’s heavy-handedness was one of his positive traits. Beard admired the fascist dictator for bringing about “by force of the State the most compact and unified organization of capitalist and laborers the world has ever seen.”

Herbert Croly, editor of the New Republic, celebrated Mussolini for “arousing in a whole nation an increased moral energy” and subordinating the citizens “to a deeply-felt common purpose.” Another New Republic editor, George Soule, praised the New Deal for its kinship to Mussolini’s policies. “We are trying out the economics of fascism.”

This flagship magazine of American progressivism praised the Mussolini regime throughout the 1920s, even publishing articles by fascist intellectuals like Giuseppe Prezzolini, who wrote that true socialism would be realized not in Russia by the Bolsheviks but in Italy by the Blackshirts.

In 1934, the leftist economist William Pepperell journeyed from his home base of Columbia University to the International Congress on Philosophy in Prague where he announced the name “Fabian Fascism” to describe the New Deal, which he considered a creative hybrid of socialism and fascism.

A few years later, in 1938, when a journalist visited Governor Philip La Follette, he found that this founder of the Wisconsin Progressive Party had two framed photographs in his office: Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis, and Benito Mussolini. La Follette admitted that these were his two personal heroes.

Some on the left went even further and praised Nazism. The progressive African American scholar W. E. B. Du Bois said Hitler’s dictatorship was “absolutely necessary to get the state in order.” In 1937 he wrote, “There is today in some respects more democracy in Germany than there has been in years past.” Du Bois even contrasted American racism, which he considered irrational, with Nazi anti-Semitism, which he said was based on “reasoned prejudice or economic fear.”

So far we’ve seen what the American left, both inside and outside the FDR administration, thought of the fascists and Nazis, but what did the fascists and Nazis think about them? I start with Mussolini’s review of FDR’s book Looking Forward. FDR’s attempt to make the whole economy work for the common good, Mussolini commented, “might recall the bases of fascist corporatism.” Indeed FDR’s whole approach “resembles that of fascism.”

When journalist Irving Cobb visited Mussolini in 1926 he said to him, “Do you know, your excellency, what a great many Americans call you? They call you the Italian Roosevelt.” Mussolini was thrilled. “For that,” he replied, “I am very glad and proud. Roosevelt I greatly admired.” Mussolini clenched his fists. “Roosevelt had strength—had the will to do what he thought should be done.” Here Mussolini is praising FDR basically for being, like him, a political strongman.

In Germany, the Nazi press also had positive things to say about FDR. On May 11, 1933, the Nazi newspaper Volkischer Beobachter, in an article titled “Roosevelt’s Dictatorial Recovery Measures” praised FDR for “carrying out experiments that are bold. We, too, fear only the possibility that they might fail. We, too, as German National Socialists are looking toward America.”

In a review of FDR’s book, the Volkischer Beobachter concluded that while maintaining a “fictional appearance of democracy,” in reality FDR’s “fundamental political course…is thoroughly inflected by a strong national socialism.” On June 21, 1934, the same newspaper noted “Roosevelt’s adoption of National Socialist strain of thought in his economic and social policies” and compared his leadership style with Hitler’s own dictatorial Fuhrerprinzip.

Hitler himself told a correspondent for the New York Times that he viewed FDR traveling down the same path as himself. “I have sympathy for Mr. Roosevelt,” Hitler said, “because he marches straight toward his objectives over Congress, lobbies and bureaucracy.” Hitler, like Mussolini, viewed FDR as a fellow dictator. Hitler added that he was the sole leader in Europe who had genuine “understanding of the methods and motives of President Roosevelt.”

Hitler also told FDR’s German ambassador William Dodd, that FDR’s insistence that American citizens place the common good above their own personal good “is also the quintessence of the German state philosophy which finds its expression in the slogan ‘The Public Weal Transcends the Interest of the Individual.’”

Even as late as 1938, Dodd’s successor Hugh Wilson reported to FDR that Hitler remained a fan. “Hitler said he had watched with interest the methods which you, Mr. President, have been attempting to adopt for the United States in facing some of the problems which were similar to the problems he had faced when he assumed office.”

It should not be assumed that FDR’s willingness to go to war with Hitler and Mussolini somehow proves that the progressives and the fascists were ideological opposites. In reality, progressivism, fascism, and communism were the three great collectivist movements of the twentieth century. All three were hostile to free market capitalism and all three sought to subordinate individual rights to the centralized power of the state.

The clashes among them were internecine ideological struggles, akin to the rivalry between kindred theologies: Catholic vs. Protestant, Sunni vs. Shia. When one sees the affinities between FDR and the progressives on the one hand, and Italian and German fascism on the other, we can see that to some degree the great wars of the second part of the century—World War II and the Cold War—were merely a contest to determine which form of collectivism would prevail.

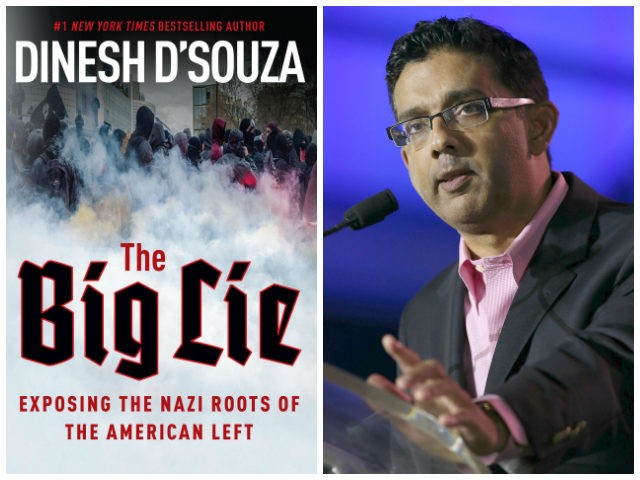

Dinesh D’Souza’s new book The Big Lie: Exposing the Nazi Roots of the American Left is published by Regnery

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.