As America confronts the coronavirus (COVID-19), we might ask: Who’s more valuable: first responders or private-equity managers? Which do we need more of right now: doctors and nurses or stock traders and their algorithms? Which is more essential: hospitals or hedge funds?

Indeed, in a time of public-health crisis, we might reflect upon some of the pillars of our society and of our social order: the mostly middle-class folks who hold up the health professions. They’re not rich, and they’re not getting rich—and yet they are putting their lives at risk. For us. For America.

Quite likely we’re going to need some heroism—actually, a lot of heroism. And when all this suffering is over, we should remember with more gratitude those who have protected us.

Because by all accounts an onslaught of disease is coming, and it’s aiming to kill some of us. According to one estimate from a pandemic official in the Bush 43 White House, perhaps half of all Americans—that’s 165 million people—will be exposed to the coronavirus. Other estimates of exposure, of course, are lower, and yet others are higher; German chancellor Angela Merkel, for instance, said on March 11 that the exposure rate in her country from the virus could reach up to 70 percent.

But if the estimate of half of Americans being exposed holds up—and again, we are only speculating here because nobody knows the future—then that could mean that roughly 27 million Americans will become seriously ill. That is, the latest information (March 9) from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention suggests that 16 percent of those exposed to the virus will be stricken, and that’s how we get that number of maybe 27 million seriously ill Americans.

In the meantime, according to the American Hospital Association, in 2020 there are a little more than 924,000 staffed beds in the U.S., and according to the Society of Critical Care Medicine, about 95,000 ICU beds.

So now maybe we should know a little bit more about the emergency and health professionals who will be charged with our care should we be stricken with corona-related medical misfortune.

We might call them the “Thin White Line,” referring to their white coats, as a variation on the “Thin Red Line” of British military history, and the “Thin Blue Line” of American policing.

As we shall see, these workers typically don’t get paid all that much; they are givers, not takers. That is, they give health and order, and take just a tiny fraction of what Wall Street Masters of the Universe pay themselves.

According to the federal Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), America employs some 262,000 emergency medical technicians (EMTs) and paramedics; they made a median salary, in 2018, of $34,320. Also according to the BLS, the nation employs 2.95 million nurses, earning a median salary of $71,730. Doctors make considerably more, of course, although if they work at a hospital, they make a lot less than they would if they were in private practice in or near a large city—and they often have huge student-loan debts to repay.

In fact, also according to the BLS, some 5.25 million Americans work in hospitals. One needn’t be a blind fan of hospitals or hospital employees to nonetheless recognize that, flaws and all, we need them.

Together, these health professionals are our centurions, guarding the ramparts of our civilization against the viral invader.

So what attack is coming? What will it be like? Once again, we don’t know, but we do know what has happened in Italy, as described by Dr. Daniele Macchini, a physician at the Humanitas Gavazzeni hospital in the city of Bergamo, as translated by The New York Post. In short, it’s a war—a war against a killer virus—and the health professionals are on the firing line:

The war has literally exploded and battles are uninterrupted day and night. But now that need for beds has arrived in all its drama.

[…]

The boards with the names of the patients, of different colors depending on the operating unit, are now all red and instead of surgery you see the diagnosis, which is always the damned same: “bilateral interstitial pneumonia.”

And there are no more surgeons, urologists, orthopedists, we are only doctors who suddenly become part of a single team to face this tsunami that has overwhelmed us.

[…]

I saw the tiredness on faces that didn’t know what it was despite the already exhausting workloads they had. I saw a solidarity of all of us who never failed to go to our internist colleagues to ask, “What can I do for you now?”

Doctors who move beds and transfer patients, who administer therapies instead of nurses. Nurses with tears in their eyes because we can’t save everyone, and the vital parameters of several patients at the same time reveal an already marked destiny.

There are no more shifts, no more hours. Social life is suspended for us. We no longer see our families for fear of infecting them. Some of us have already become infected despite the protocols.

This is stoicism and heroism, pure and simple. Indeed, we can take special note of words and phrases in Dr. Macchini’s witness, words such as “solidarity” and “single team,”—and, of course, “battle” and “war.”

We might not ordinarily think of doctors and other health professionals as warriors, but that’s what they are: They are fighters in the combat against disease, disability, and death. In a tweet on the 11th, Trump caught this militant spirit, declaring the virus to be “a common enemy … an enemy of the world.” And in his Oval Office speech to the nation later that evening, he sounded more appropriately martial notes, declaring, “We’re all in this together,” and adding “We will overcome.” And on the 13th, Trump spoke from the White House Rose Garden, declaring a formal state of emergency for the nation in order to “combat” the virus, and yes, to “win.”

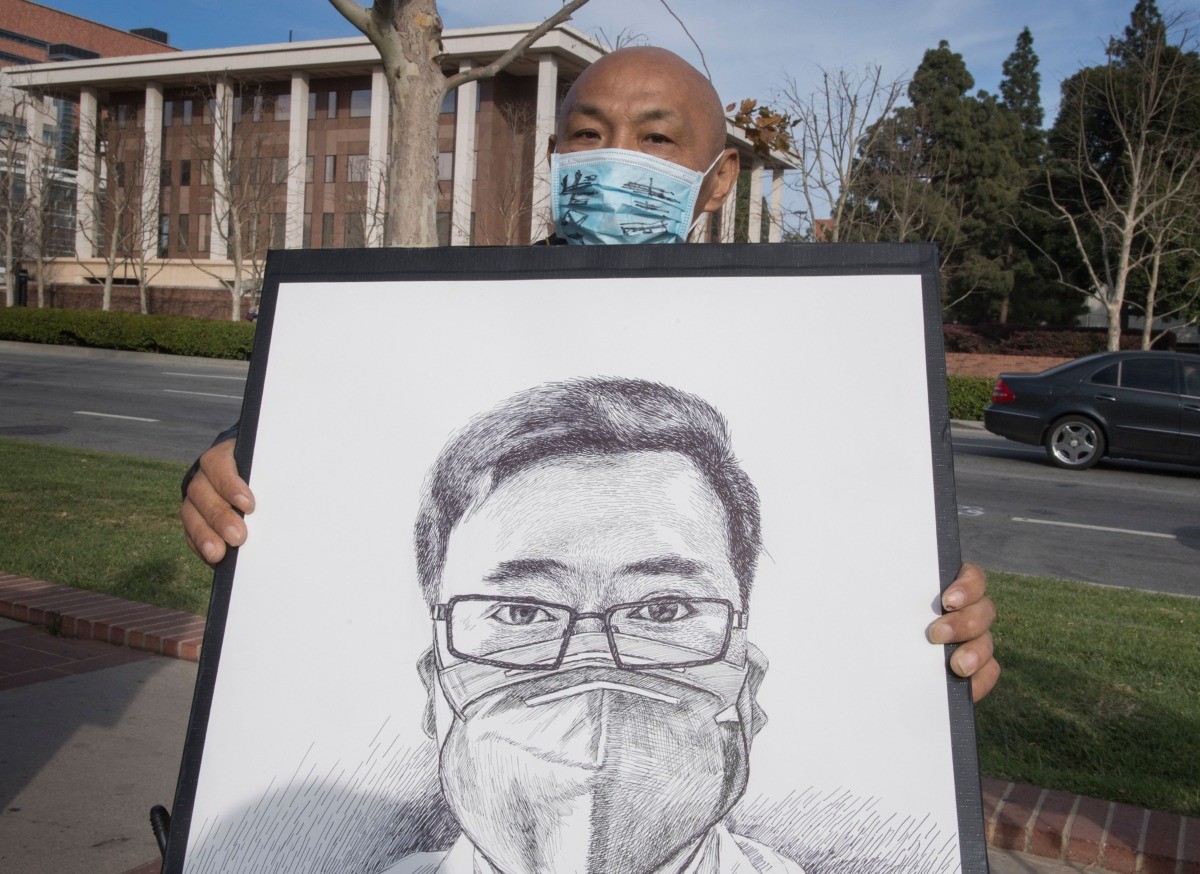

Supporters hold a memorial service in Westwood, California, for Dr. Li Wenliang, the Chinese whistleblower who alerted the public to the coronavirus (COVID-19) that originated in Wuhan, China, and ultimately caused the doctor’s death. (MARK RALSTON/AFP via Getty Images)

An elderly patient in northern Italy is helped by a doctor at one of the emergency centers, on March 12, 2020. (AP Photo/Luca Bruno)

Paramedics work in a tent that was set up outside the hospital of Cremona, northern Italy, on February 29, 2020. (Claudio Furlan/Lapresse via AP)

Paramedics work at one of the emergency structures at the Brescia hospital, northern Italy, on March 12, 2020. (AP Photo/Luca Bruno)

Nurses wait for patients at the main entrance of the Brescia hospital, northern Italy, on March 12, 2020. (AP Photo/Luca Bruno)

Hospital employees wearing protection masks and gear tend to a patient at a temporary emergency structure at the Brescia hospital, Lombardy, on March 13, 2020. (MIGUEL MEDINA/AFP via Getty Images)

Red Cross personnel deliver medical supplies door to door in Rome on March 13, 2020, as Italy is on lockdown to slow the spread of the coronavirus. (Mauro Scrobogna/LaPresse via AP)

A person is loaded into an ambulance on March 12, 2020, at the Life Care Center in Kirkland, Washington, near Seattle. The nursing home is at the center of the coronavirus outbreak in Washington state. (AP Photo/Ted S. Warren)

Kirkland Fire and Rescue ambulance workers walk back to a vehicle after a patient was loaded into an ambulance on March 10, 2020, at the Life Care Center in Kirkland, Washington, near Seattle. (AP Photo/Ted S. Warren)

Workers from a Servpro disaster recovery team wearing protective suits and respirators enter the Life Care Center in Kirkland, Washington, to begin cleaning and disinfecting the facility on March 11, 2020. (AP Photo/Ted S. Warren)

Medical University of South Carolina healthcare providers dress in protective suiting as they get ready to see patients by the hospital’s drive-through tent for people being tested for coronavirus on March 13, 2020, in Charleston, S.C. (AP Photo/Mic Smith)

Workers in protective gear operate a drive through coronavirus mobile testing center on March 13, 2020, in New Rochelle, New York. (Spencer Platt/Getty Images)

A nurse swabs for coronavirus at the University of Washington Medical center in Seattle, Washington, on March 13, 2020. (John Moore/Getty Images)

Nurses check registration lists before swabbing patients for coronavirus at the University of Washington Medical center in Seattle, Washington, on March 13, 2020. (John Moore/Getty Images)

Bolstered by that sort of fighting leadership, there’s a good chance that the Thin White Line will prevail–perhaps sooner than most people realize. Indeed, on the 12th, we learned that an Israeli company is already far along in its quest for a vaccine. We can observe that strong science makes for the best medicine, even as we still look on with awe at those who are willing to stand up in person to deadly disease.

Indeed, in regard to this Thin White Line, we might recall the admiring question asked by an admiral at the end of the 1954 Korean War movie, The Bridges at Toko-Ri, as he thinks about the courage of his naval aviators: “Where do we get such men?”

Today, of course, the issue is courage and fortitude in the health war, and so we must ask, “Where do we get such men and women?”

One reason for this medical courage is that most health professionals in many countries have taken the Hippocratic Oath, an ancient code of medical ethics that still lives in the hearts of the oath-takers. It declares in part, “In purity and according to divine law will I carry out my life.” Today, to many cynics and greedheads such an earnest oath might seem to be just so much retro hooey, and yet in fact, to its loyal adherents, an oath means a great deal—and even in some situations it means everything.

In the weeks and months to come, most of us will be counting on this Thin White Line. So as we think of them, we might wonder a bit about the disparity between the Thin White Line and the Upper Crust—that is, the one percent who seem ever more disconnected from the rest of us, even as they benefit from the sacrifice of dedicated professionals.

For instance, we might ask ourselves: Is it the case that Michael Bloomberg, boasting a $60 billion fortune, is really one million times more valuable than a nurse making $60,000 a year? Is it right that Bloomberg’s $60 billion is a million times the amount of a nurse’s annual salary?

Indeed, despite squandering a few hundred million of his fortune on his vainglorious presidential campaign, Bloomberg’s wealth continues to grow; estimates suggest it is increasing by a couple billion dollars every year.

Is this fair? Is this just? That is, that Bloomberg makes so much while front-line professionals make so little? One doesn’t have to be a radical or anything close to see the inequity of the status quo.

We can do more than just think with solemn respect about the Thin White Line.

We can also think about the Thin Blue Line of workers who are tasked with keeping order come what may. Maybe both of these Lines deserve a big pay raise, as well as the salute of a grateful nation.

So if that means that the Goldman Sachs/Bloomberg class pays more in taxes, is that so wrong? If some are about to give all in the health war, then all ought to give at least some.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.