The Conservative Party is likely to drop a 2015 pledge to withdraw Britain from the European Convention on Human Rights, leaving Britain bound by the convention for at least another five years.

A fresh pledge to commit to withdraw from the ECHR by the end of the next Parliament, in 2022, was expected as Prime Minister Theresa May previously indicated her support for the move.

During her time as home secretary between 2010 and 2016, Mrs. May grew increasingly frustrated with the ECHR, not least because for a while it thwarted her plans to extradite hate preacher Abu Qatada.

The 2015 Conservative manifesto stated: “The European Court of Human Rights has developed ‘mission creep’. Strasbourg adopts a principle of interpretation that regards the Convention as a ‘living instrument’.

“Even allowing for necessary changes over the decades, the ECHR has used its ‘living instrument doctrine’ to expand Convention rights into new areas, and certainly beyond what the framers of the Convention had in mind when they signed up to it.”

That manifesto promised reforms which would reduce the influence of the ECHR to a mere “advisory body” without the powers to change UK law.

It also promised to replace the Human Rights Act with a British Bill of Rights.

However, senior party figures have told The Telegraph that the pledge is unlikely to feature in the party’s new manifesto when it is published in the week of May 8th, as the government is concerned that pursuing the pledge will distract from Brexit.

One senior minister said: “We have so much on our plate that we just don’t have enough time to do this. We have enough to do with Brexit let alone the ECHR.”

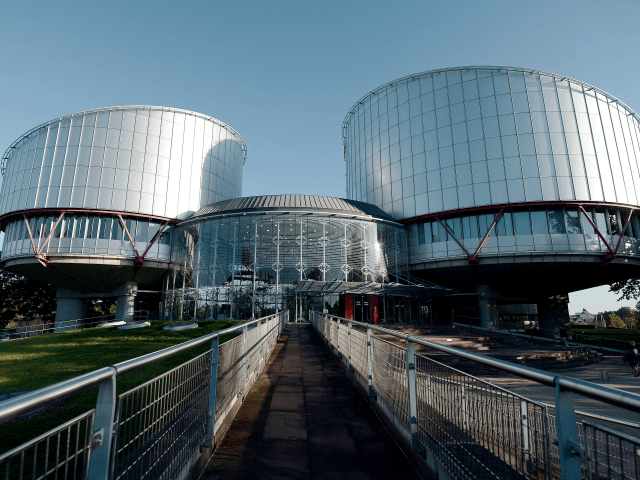

The convention is a post-war treaty dating back to 1953 to which all members of the Council of Europe are bound. Setting out a list of freedoms and rights for citizens, the treaty also established the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg, France.

Both entities are entirely separate from the European Union; nonetheless, party figures are concerned that, at a time at which they are currying for the good will of Britain’s European neighbours, withdrawing from the convention would send the wrong message.

One cabinet minister said pursuing withdrawal would project the wrong “values” and could “screw up” Brexit negotiations, while another questioned why Mrs. May would muddy the waters instead of allowing herself a clear five years to get Brexit out of the way.

Martin Howe QC, who drew up the plans for the last Conservative manifesto, said he “fully understood why Brexit must be put first” but urged Mrs. May to include a reference to the policy in the new iteration.

“They would be well advised to at least keep the option open of reforming human rights law and possibly withdrawing from the convention if that proves to be necessary,” he said.

A party source said the situation was “fluid at the moment, different people have different views on it”, adding that a final decision had not yet been made.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.