MEXICO CITY (AP) — Cartel kingpin Nazario Moreno Gonzalez played dead for more than three years, putting on one of the greatest performances in drug-trafficking history.

The Mexican government had delivered him the perfect alibi: The head of the vicious cartel based in the western state of Michoacan had been killed in a shootout with federal police, they announced in December 2010.

Not only did Moreno change the name of his organization while operating in the shadows, he became more powerful. He expanded from cooking and trafficking methamphetamines to extorting and intimidating everyone across the mineral- and agriculture-rich state, from families to the giant lime, avocado and mining industries.

“He was the biggest beneficiary of his anonymity,” said Alfredo Castillo, the federal commissioner who was sent in January to take back control of the violent state. “It kept him playing the game.”

The game ended early Sunday when Mexican soldiers and marines confronted Moreno in Timbuscatio, a town in the remote mountains. Officials said the troops fired to respond to an “aggression” as they tried to arrest him.

Authorities now had something that was missing the first time: his body.

Tomas Zeron, head of the criminal investigation unit for the federal Attorney General’s Office, said Moreno’s identity had been confirmed by fingerprints.

Michoacan residents had long said they had seen Moreno, known as the “The Craziest One.” They said he carried a Bible and wore priest-like robes as he directed the gunmen of the pseudo-religious cartel he built using a mish-mash of evangelical Protestantism and symbols lifted from history.

Moreno was seen at cock fights and parties by people who knew him as a local boy who grew up in the farming hub of Apatzingan, before he spent his teenage years in the United States.

He would came down from the mountains to induct new recruits, officiating at ceremonies “where he gave people wine to drink” in a strange version of the Eucharist, said Estanislao Beltran, the spokesman for the vigilante movement that rose up a year ago to fight the Templars.

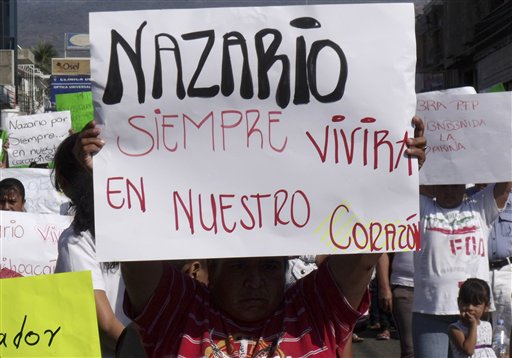

Meanwhile, the Knights Templar promoted Moreno’s “death,” building small roadside shrines to “Saint Nazario” in dozens of towns. His No. 2, Servando “La Tuta” Gomez, who is still at large, confirmed Moreno’s 2010 “death” in one of his many YouTube videos.

“This was a strategy on their part, so the government would stop bothering them and leave their boss in peace,” said the Rev. Gregorio Lopez, a Roman Catholic priest in Michoacan who supports the vigilantes.

When Castillo arrived, he started receiving anonymous and tips and emails, even photos of Moreno taken from a distance. Authorities made composite sketches, Castillo told Milenio Television. But Moreno was hard to track.

“He moved from place to place and town to town,” said Interior Secretary Miguel Angel Osorio Chong.

Before the Knights Templar, Moreno founded La Familia cartel, the first target of former President Felipe Calderon’s assault on Mexican drug trafficking in 2006.

La Familia reportedly took its inspiration from an odd source: the book “Wild at Heart” by American evangelical author John Eldredge of the Colorado Springs, Colorado-based Ransomed Heart Ministries. A Mexican government profile said Moreno “erected himself as the ‘Messiah,’ using the Bible to profess to poor people and obtain their loyalty.”

He set a code of conduct that prohibited using hard drugs or dealing them within Mexican territory.

The Templars also distributed literature and preached faith in God and a moral code.

“It was great theater to show that you were a follower,” said Ramon Contreras, a town official in La Ruana and member of one of the civilian “self-defense” groups.

Only when the vigilante groups took up arms in February 2013 and began driving the Knights Templar from much of the state’s Tierra Caliente farming region did the federal government react. After sending troops in more unsuccessful attempts to quell the violence, Castillo was assigned commissioner to take over the state.

With a series of key arrests in recent weeks, Mexican authorities finally closed in.

According to the autopsy, Moreno had a metal plate in his skull, Castillo said, indicating he may have been wounded in the 2010 shootout.

Now he was dead again, but as Mexican newspapers noted Monday: “This time for real.”

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.