In his first inaugural address as president of the United States, George Washington said, “The sacred fire of liberty and destiny of the republican model of government are justly considered, perhaps, as deeply, as finally, staked on the experiment entrusted to the hands of the American people.”

On George Washington’s 282nd birthday celebration, it is important to look back on the qualities that made Washington such a great republican leader, and the legacy he and the people of his generation bequeathed to Americans.

Often mistakenly called “President’s Day,” the third Monday of February officially became a federal holiday in 1879 to honor George Washington (his birthday actually falls on February 22). Though there are many other presidents worthy of celebration and respect, none quite matches the “Father of Our Country” in symbolizing the president’s office and the United States. Washington was not only a great leader, with profoundly admirable personal qualities, but was the model statesman for a revolutionary new republic in a sea of monarchical and authoritarian governments.

Americans first started commemorating George Washington’s birthday in the late 1780s Virginia, and it was mostly celebrated by Federalists, one of the first two “parties” under the new Constitution. The holiday’s partisan roots are not unusual. Celebrations on Independence Day in that time period were mostly orchestrated by supporters of Thomas Jefferson’s “Democratic-Republicans.”

This trend of associating a patriotic holiday with a political persuasion continues today, as there have been noted studies about how Fourth of July celebrations push people to the Republican Party and political conservatism. It is appropriate to commemorate Washington’s life on this day regardless of the holiday’s partisan origins. As Thomas Jefferson said in his first inaugural address, “We are all Republicans, we are all Federalists.”

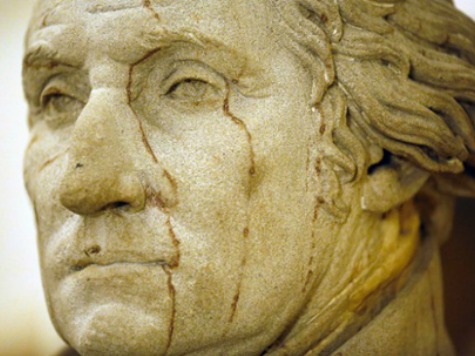

Though the image of Washington is often that of a stiff old man, the epitome of a fatherly, restrained elder statesman, it is easy to forget what a bold, fiery, and perhaps a reckless young man he was.

Having received less formal education than anyone who has served as president, Washington was educated in the rough conditions of frontier life. A prodigious youth seeking honor and glory, Washington entered military service and became a small-time hero to Americans at a young age. Fighting in the Seven Years’ War (called the French and Indian War in the U.S.), which he actually sparked in a botched negotiation with French diplomats, Washington earned a reputation for incredible bravery and energy. He became commander-in-chief of the Virginia military at the age of 22, stunningly young even for that time period.

Though Washington performed ably during the war under very difficult conditions, his fighting record was not an unmitigated success. The failures he experienced in his first war helped him grow into the leader he was to become in the next.

Historian James Thomas Flexner noted of Washington’s early military record in his Pulitzer Prize winning Washington: The Indispensable Man, that, “He was from the first never a follower, always a leader even if somewhat subject to greater authority than his own.” This quality of always leading, but respecting higher authority would serve him well in the far greater conflict that lay ahead, one in which he would undoubtedly become the “indispensible man.”

Despite some notable failures in the French and Indian War, Washington believed his service deserved recognition and he requested a commission as an officer in the regular British Army. He was denied due to his youth, lack of high aristocratic birth, and most importantly, for being a provincial, American-born colonial. So, Washington resigned from the militia and returned to civilian life. Snubbing George Washington may have been the worst decision in the history of the British Empire.

When the American colonies rose in rebellion, in reaction to the heavy-handed policies of England, colonial leaders turned to Washington (who wore his uniform to the Continental Congress) as the only man with the recognition and distinction to lead the Continental Army. As a wealthy man of status, however, Washington had much to risk in taking up the cause. He believed that in the end, military opposition to and eventual independence from England were necessary for the freedom and growth of the American people.

Historian Flexner wrote that Washington was keenly aware of the nearly impossible challenge put before him and quoted Washington as saying after the war that he knew the struggle would be “protracted, dubious and severe. It was known that the resources of Britain were, in a manner, inexhaustible, and that her fleets covered the ocean, and that her troops had harvested laurels in every quarter of the globe…”

Knowing the power of England from his first-hand experience in the British Army, and understanding that the poor, scattered, divided American colonials were at an extreme economic and military disadvantage, he chose to dutifully fight for his new country anyway.

It has been argued by some commentators and historians that Washington was not a particularly able general, that his battlefield tactics were average to subpar, and that his success came from a combination of luck and an array of able lieutenants. These people think too small.

The best battlefield tactician, on either side of the war, was turncoat Benedict Arnold. Arnold, of course, put himself before the cause. In a vain drive for personal military glory, he betrayed his fellow patriots for the prestige of the British Army. George Washington was made of different stuff, staying absolutely committed to the cause of the American people, despite whatever setbacks and depredations he received at the end of an often incompetent Continental Congress.

Benjamin Franklin said of Washington’s generalship to a British friend after the war, “An American planter was chosen by us to command our troops and continued during the whole war. This man sent home to you, one after another, five of your best generals, baffled, their heads bare of laurels, disgraced even in the opinions of their employers.”

To say that Washington was anything less than a great general misses the bigger picture.

He miraculously kept a woefully unprepared and undersupplied Continental Army together for almost a decade and knew when to pick his fights to achieve ultimate victory and independence. On top of that, he performed perhaps the most important task of all that required far more than simply a powerful, ambitious conqueror.

It has almost become cliché to explain how Washington rejected power and stepped down from his position at the end of the war. Channeling the famous Cincinnatus, who was made dictator of Rome and then returned to his farm and plow when their enemies were defeated, Washington left the military and returned to private life when his victory was complete, even though he could have selfishly grasped for power.

However, before he stepped down, Washington had to make a dramatic stand against a large contingent of his own officers who wanted to make him king and depose the Continental Congress. He convinced his war-weary men to back down after he pulled out a pair of glasses to read a speech and said, “Gentlemen, you will permit me to put on my spectacles, for I have not only grown gray but almost blind in the service of my country.”

When the Constitution was ratified and the nation needed to elect its first president, there was no doubt that it would go to anyone but Washington. In an era that was as fractious and politically divided as any in our history, Washington rose as a unanimous pick to be the chief executive. He served, as always, humbly and ably, a steady hand at the wheel of a fragile, fledgling republic. When his second term was up, he gladly returned to his home at Mount Vernon, and left the burgeoning nation in the hands of the American people.

Washington reached an unparalleled level of success and accolades because of both his strength and his restraint. Only these qualities could have guided a revolutionary new nation through its bumptious early days. He ushered in a new order for the ages, where the people, not kings and tyrants, ruled; where leaders with plain republican titles like “president” and Constitutionally limited offices had more dignity, merit, and power than any king, dictator, or unlimited government body.

Unfortunately, the modern world has weak comparisons to Washington. The United States currently has a president who intentionally diminishes the power of his own country, is unwilling to stand for its incredible legacy on the world stage, and timidly shirks any suggestion that America is a truly exceptional country.

On the other side of the spectrum is Russian leader Vladimir Putin, who has attracted a few accolades from Americans tired of their own weak and ineffective leadership. However, Putin also fails to match Washington’s example of leadership. He is little more than a thuggish, authoritarian goon, exhibiting strength but not virtue and restraint. Like a small-time Napoleon or mob boss, he will do little more than maintain order and power, fading quickly into the sands of history when his reign ends.

But the Father of Our Country proved how a great and good leader could bring happiness and prosperity to far more than himself or simply a few select individuals of his own generation. When King George III heard that Washington would step down from his military commission at the end of the Revolutionary War, he remarked that it would make him the “greatest man in the world,” and so he was.

The great early American historian Forrest McDonald perfectly summed up the great man’s legacy in The Presidency of George Washington:

George Washington was indispensible, but only for what he was, not for what he did. He was the symbol of the presidency, the epitome of propriety in government, the means by which Americans accommodated the change from monarchy to republicanism, and the instrument by which an inconsequential people took its first steps toward becoming a great nation.

Without the dramatic writing flair of Thomas Jefferson, nor the profound policy acumen of Alexander Hamilton, Washington rose to greatness because of his strength, devotion to duty, and absolute commitment to the republican cause that was a unifying force to Americans looking for leadership. He was such a historic unifying force to the nation that, even during the Civil War, his home at Mount Vernon was considered neutral ground.

George Washington believed in the future greatness of his country more than himself and carried the “torch of liberty” as long as his country needed him. He was the model and epitome of strong, republican leadership that all American leaders should try to emulate.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.