Chinese dictator Xi Jinping — credibly accused of a wide variety of crimes against humanity against his own people and multiple ethnic cleansing campaigns, at least one rising to the level of genocide — is expected to land in San Francisco next week.

The Communist Party chief will arrive in California on November 14 “at the invitation of U.S. President Joe Biden,” the Chinese Foreign Ministry confirmed Friday, to attend the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) Economic Leaders’ Meeting. The expectation for Xi’s visit to America, his first in six years, is that he will be greeted by a parade of groveling CEOs, eager sycophants and wannabe investors, and an American president who has dismissed genocide as a minor difference in “cultural norms.”

Xi should be greeted with handcuffs.

In this photo released by Argentina’s press office, China’s President Xi Jinping touches a polo horse gifted to him by Argentina’s polo association, as Argentina’s President Mauricio Macri hosts him at the Olivos presidential residence in a northern suburb of Buenos Aires, Argentina, on December 2, 2018, (Argentina’s presidential press office via AP)

In 2018, when Xi Jinping visited Argentina for the G-20 summit hosted by Buenos Aires, I called for his arrest there on the grounds that evidence strongly implicated his leadership in crimes against humanity. Under international law, some crimes are considered jus cogens, or peremptory norms: crimes that the entire world agrees are crimes and no nation can dismiss. The Vienna Convention, which governs how treaties are written and adopted, prevents countries from erasing peremptory norms by agreeing to ignore them — treaties that violate jus cogens are invalid. Peremptory norms are considered so important to prosecute that they create “universal jurisdiction,” meaning any court in the world can prosecute a case against anyone should evidence exist that they violated such a norm. International law considers it legitimate for any country in the world to arrest someone credibly accused of genocide and other peremptory norm violations, regardless of where they allegedly occurred.

“Universal Jurisdiction is based on the idea that since perpetrators who commit such heinous crimes are hostes humani generis — ‘enemies of all mankind,'” the Center for Justice and Accountability explains, “any nation should have the authority to hold them accountable, regardless of where the crime was committed or the nationality of the perpetrator or the victim.”

Crimes against humanity, genocide, and war crimes are the three most widely recognized peremptory norms. International law in the post-World War II era has uncontroversially accepted that dictators who commit these crimes can be prosecuted anywhere. When Spain processed a case against Chilean Gen. Augusto Pinochet in the late 1990s for human rights atrocities at home, Human Rights Watch noted that universal jurisdiction is “firmly enshrined in Spanish legislation and international law.” Similar legal standards were used in March when the International Criminal Court (ICC) issued an arrest warrant for Russian leader Vladimir Putin in response to evidence of war crimes committed in Ukraine.

Russia’s President Vladimir Putin (R) shakes hands with his China’s counterpart Xi Jinping (SERGEI CHIRIKOV/AFP via Getty Images, File)

With those standards established, the case for arresting Xi in Argentina was clear. Five years later, the body of evidence against Xi is far more robust.

At the time, in 2018, human rights groups were calling for a similar arrest of Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman in the aftermath of the gruesome killing of Islamist Washington Post columnist Jamal Khashoggi, but few placed Xi in the same category, despite ample evidence of widespread human rights abuses. Publicly available evidence in 2018 implicated Xi in the disappearance of most of the nation’s high-profile human rights lawyers; the eradication of Tibetan Buddhism, language, and culture in the occupied territory; live organ harvesting of political prisoners, prominently those belonging to the Falun Gong spiritual movement; and the mass arrests, torture, and killing of Chinese Christians. Some reports had begun to suggest a sprawling campaign to destroy the Uyghur people of occupied East Turkistan, including the use of concentration camps to imprison civilians and indoctrinate them into communist atheism, but had yet to fully materialize.

No such arrest occurred and Xi’s body count has grown exponentially since then — as has evidence that the extermination of Uyghurs and other Turkic communities in East Turkistan is both a clear example of genocide and a crime orchestrated by Xi personally.

In 2021, an organization known as the Uyghur Tribunal — a group of independent international legal experts — hosted an investigation into the allegations of genocide against China, listening to eyewitness testimony of what life is like in China’s concentration camps. In 2019, at the peak of the mass arrests of Uyghurs under Xi, the Pentagon revealed evidence that up to 3 million people were forced into concentration camps. The witnesses detailed constant communist indoctrination, brutal torture, mass rape (including with electric batons and other torture devices), forced sterilization, and slavery.

This photo taken on May 31, 2019, shows the outer wall of a complex which includes what is believed to be a re-education camp where mostly Muslim ethnic minorities are detained, on the outskirts of Hotan, in China’s northwestern Xinjiang region. (GREG BAKER/AFP via Getty Images)

Outside of the camps, the Uyghur tribunal documented evidence of children being torn from their families, educated in communist schools, and forced to learn Mandarin, a language native to the Han people of eastern China and not indigenous to East Turkistan. Doctors testified to the mass sterilization of women, including the sterilization of entire villages at once, and forced abortions to keep the population low.

The Uyghur Tribunal found Xi’s regime guilty, “beyond a reasonable doubt,” of genocide, which international law defines as the “intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group.” The definition of genocide includes the forced sterilization of women, mass killings of people of the targeted group, and the abduction of children in the group away from their parents.

In 2022, a massive leak of Communist Party documents published by researcher Adrian Zenz and the Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation, known as the “Xinjiang Police Files,” offered definitive evidence that Xi was personally leading the execution of the Uyghur genocide, rather than looking the other way as his underlings committed heinous crimes. The documents included multiple speeches by high-ranking government officials who repeatedly credited Xi with the idea of exterminating the Uyghur genocide. Chen Quanguo, the Communist Party secretary of occupied East Turkistan at the beginning of the genocide, personally attributed the creation of the concentration camps to Xi in the documents. Other officials attributed to Xi the idea of “breaking lineages, breaking roots, breaking connections, breaking origins” in East Turkistan to destroy the existence of the region’s indigenous culture and people.

Similar programs have been implemented in other territories controlled by the Chinese Communist Party that do not have majority Han populations. In Tibet, the Party has established a similar system of concentration camps and stolen children away from their parents en masse; Tibetan Buddhism is illegal and considered a dangerous separatist movement. A similar, though smaller, program has been implemented in Inner Mongolia to erase the indigenous Mongolian culture, prompting widespread protests against the regime.

Xi Jinping is expected to meet with Joe Biden on Wednesday, CBS News reported on Friday, citing anonymous alleged American officials who say that Biden will prioritize “restoring” friendly ties to China and improved communication with the Communist Party. Human rights groups have begun suggesting to Biden that he raise China’s abuses against its people and those subjugated under communist occupation in that meeting, but at press time have stopped short of demanding a valid arrest under international law.

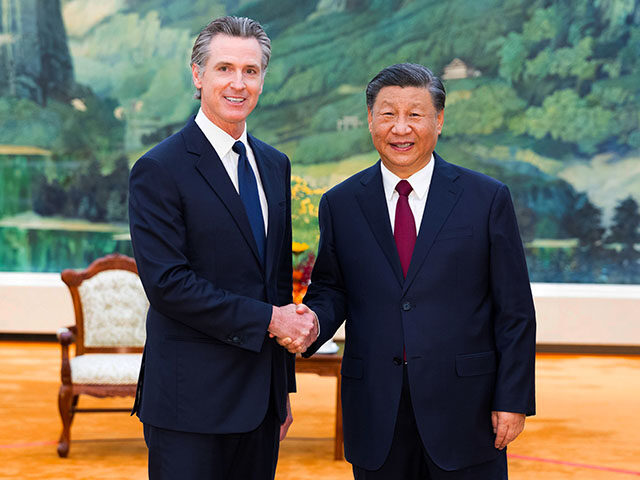

The hesitance to do so is likely fueled by how friendly America’s Democrat Party is to the Communist Party — the governor of the state Xi is visiting next week, Gov. Gavin Newsom, paid his respects to Chairman Xi in Beijing’s “Great Hall of the People” less than a month ago, vowing to turn the state into “China’s long-term, stable, and strong partner.” Xi is unlikely to be met by any sort of justice next week. But his record as a leader and the body of evidence against him for committing crimes universally accepted as among the most egregious violations possible is clear — and the international community, including the American justice system, should recognize it.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.