Union City’s embroidery culture began long before the incorporation of Union City – in Switzerland, with the birth of the Schiffli machine.

Prior to the invention of the Schiffli, embroidery was all but impossible to mass produce. Sewing machines helped, but ultimately still required one person to sew elaborate lace designs alone, one project at a time. Automation revolutionized the industry, allowing embroidery to remain a job skill – running those machines required experience – but making decorated textiles suddenly much more accessible in the Western world to the average citizen.

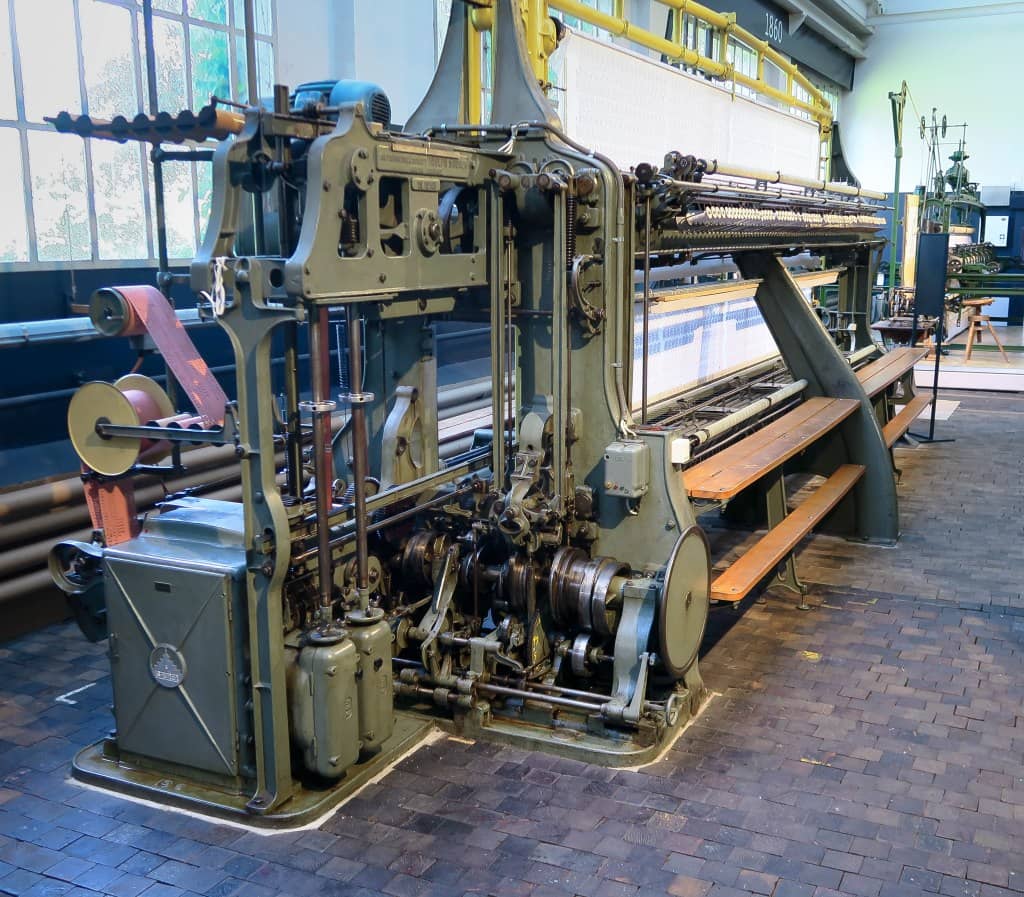

Isaak Gröbli built the first Schiffli embroidery machine in 1863 by essentially making a giant version of the individual-sized sewing machine. The Schiffli monstrosity takes in yards of thread at a time, weaving predetermined designs into the fabric introduced into it. The Schiffli is electric and, according to those who have managed one, does make some errors, requiring an army of “menders” to perfect the designs following the machine’s work. But it allowed for mass production in an unprecedented way and was so ahead of its time that it is still used to this day.

The weaving threads inside of a large, multi-ton husk of machinery made the machine look like a boat, so it was christened the “Schiffli,” or “little boat,” in Swiss German.

The Schiffli was born into a world in which immigrant waves of Europeans were flooding the eastern shores of the United States, in particular the New York Harbor area, so it took very little time for the machine to find its way to New Jersey, where all the immigrants New York’s elite did not want to see on their way to their cocktail parties always seem to end up. New Jersey has had one of highest foreign-born populations in the United States consistently since 1860.

Robert Reiner, a German immigrant, takes the credit for bringing the Schiffli to the North Hudson area, specifically Weekhawken, which borders Union City to the east. Reiner arrived across the Hudson in 1903 looking for ground sturdy enough to support the mammoth invention.

“The machines could weigh up to six or seven tons and they were actually bolted through the factory floors into the granite, into the earth, to keep the buildings from shaking,” Gerald Karabin, Union City’s official historian, tells me. “For this area, that’s what actually put the embroidery machines here. This part of the country, this area was excellent for that set up.”

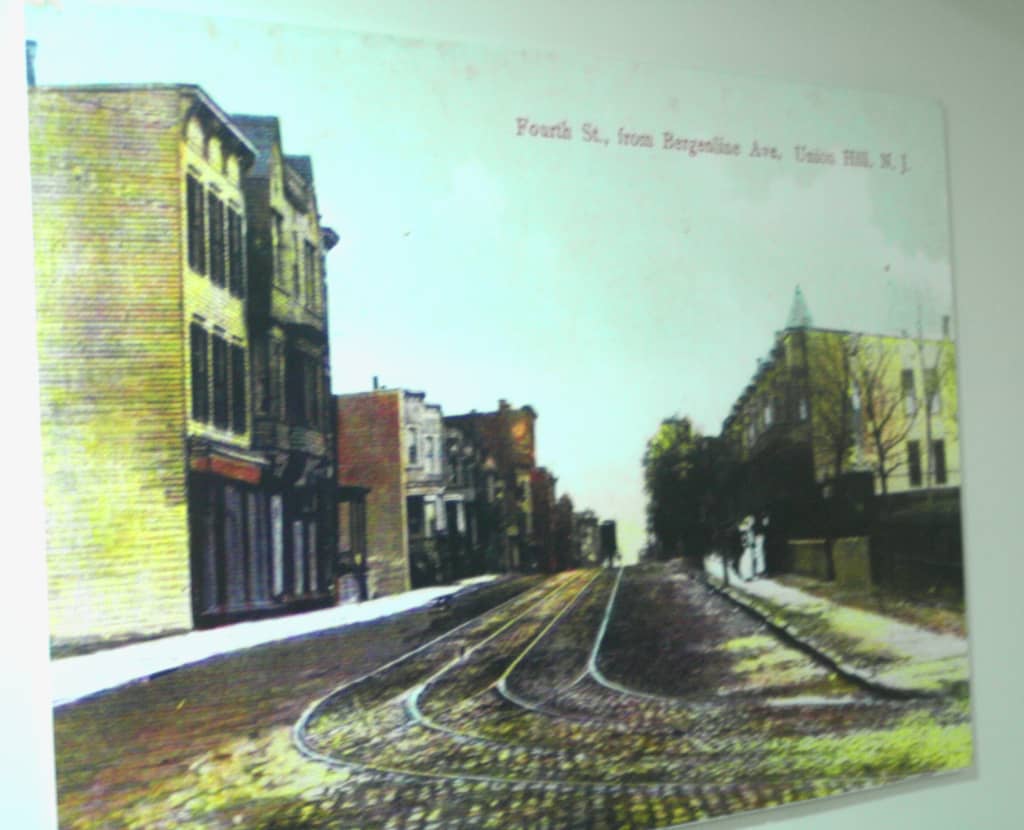

Reiner arrived in a largely German, mostly immigrant North Hudson, one that had been so for a while. Union City would not exist for another 23 years; at the time, the territory covering Union City – all two miles of it – was split into two municipalities, the towns of Union Hill and West Hoboken. Karabin describes the North Hudson of the 1840s as sleepy and sparsely developed, in need of clean water and basic living supplies that later came with the construction of two reservoirs and a water tower in Weehawken.

“When the reservoirs came, there was a big building boom in Union City because now you could build apartment buildings actually, three to four stories high, and supply them with water that supported a larger population,” he explains. Building infrastructure required workers, and keeping the workers as taxpayers required building infrastructure, so the development reinforced population growth. The nature of the work that development requires attracted immigrants.

“German immigrants in the 1850s were looking to get out of crowded New York City or Midtown and, at that time, Union Hill was farmland, basically, so they came over and started their own little businesses,” Karabin explains.

The pre-Union City that welcomed Reiner was diverse and rich in potential labor. The Union Hill and West Hoboken of the 1800s boasted renowned German breweries and smaller textile enterprises of all ethnic backgrounds. Along its commercial districts, streetcars offered access to local shops and restaurants or, further down, the shipping ports of Hoboken. Hoboken, sitting across the Hudson River from Manhattan’s Garment District, offered a door to one of the largest markets for domestic production in the world at the time.

With the exception of New York old money, almost all found a home in Hudson County. According to Karabin, an 1890 local census found as many as 29 different ethnic groups living in a five-block radius in West Hoboken “in relative peace and harmony.” The locals called the neighborhood the Dardanelles, an homage to the strait separating Europe from Asia in Turkey.

Important to the Schiffli narrative is that these immigrants – from Germany, Switzerland, Austria, and other parts of Europe – came recently to America and had experience in textile industries. The first Schiffli machine Reiner imported to the United States set off a market chain of hundreds of imports throughout North Hudson and attracted even more labor.

“Not everybody can get on working those machines and you had immigrants at that time that were from Europe, Germany, Switzerland, France, Italy, that may have been familiar with that process from their home countries, so they had something to offer,” Karabin explained. “As amazing as these Schiffli machines were, it wasn’t as mechanized, like a production line – if you were an employee that could work that machine, you were valued by the owner.”

“A lot of these folks had no education, but even when they had no education they had skills, a lot of them were doing this kind of work in the old country,” Alan Tonelson, founder of the economics and public policy blog RealityChek, told me. I had called Tonelson for help analyzing the global trade deals that ended American manufacturing at the turn of the century but, like so many I reached out to in writing this article, his grandfather had worked in embroidery in New York.

“You had wave after wave of low wage immigrant labor like my grandparents, even if they were skilled,” Tonelson noted. “[My grandfather was a] proud member of the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union and, in fact, he was a plant foreman … these were then very good ways for immigrant families to make their livings.”

Tonelson noted that Union City was far from unique in enjoying a manufacturing boom in the early 20th century that expanded into the modern era.

“You have General Electric making locomotives near Buffalo and all sorts of things like that, and Erie, Pennsylvania, and the whole state of Pennsylvania, was a whole steel making center,” he noted. “And later on you had computer manufacturing, many of it located in the Route 128 corridor located around Boston. So there’s no question that the Northeast has had a very big and long and rich history of manufacturing.”

By the time Union City was founded on June 1, 1925, embroidery had become so integral to the existence of its residents that the “little boat” made its way onto the official seal of the city.

Weaving American Identity

Industry, embroidery in particular, made Union City moderately prosperous. Karabin, the historian, narrated to me that the early German immigrants developed businesses that later provided ample opportunity for other immigrants, particularly Italians and the Irish.

“When they came to America, which already had a German population, you know, of some size, I think they integrated quite rapidly and went to businesses,” he noted. “Many of these embroidery factories were actually investments of some of these earlier settlers … let’s say 3 people put in $10,000, created a company, invested in it.”

The money attracted laborers of other nationalities, who happily coexisted with the Germans and vice versa, as historic documents and narratives relate. Anti-Catholic bigotry targeting Italians and the Irish seeped into bigger neighboring cities like Jersey City[1] – and New Jersey itself did not allow non-Protestants to hold public office until 1844 – but not so much its tiny neighbor, potentially because the “elites” in Union City by the 1930s and ‘40s were Germans and Swiss who came half a century before. Before the German and Swiss, the toxic water in the area simply could not sustain a significant population, so the immigrants never displaced any native-born Americans.

As an immigrant community built from scratch, Union City attracted not just the elite’s undesirables but their “undesirable” culture. Embroidery money empowered the children of the first generation to live in Union City to invest in other types of businesses: local banks, restaurants, shops of all kinds, and leisure spots.

According to the documentary film Union City, U.S.A., directed by local celebrity and Public Affairs Commissioner Lucio Fernandez, the city developed a reputation for performance and entertainment in the 1930s with the construction of the Park Theater, now known for the longest-running Passion Play in the country, a stage play retelling the last days of Jesus Christ hosted every Holy Week leading up to Easter. It also attracted burlesque theater, which found a home close to the entrance to the Lincoln Tunnel, particularly after New York City banned stripping in 1933 and the tunnel opened in 1937.

Placing burlesque venues too hot for New York City in the same two-mile radius as a premier performing arts venue owned by the Archdiocese of Newark sounds like a recipe for disaster, even without taking into consideration at least 29 different ethnicities cohabitating the space. Yet Karabin tells me he has seen no evidence of ethnic or racial conflict in the history of the city.

“For some reason, Union City, I really haven’t seen … anything really like a race riot or something like that,” he notes. “It never really occurred. There were some incidents in the 1920s during the labor movement that involved Italian Americans, you know, but that included a lot of people who were trying to unionize and you were branded a communist [if you did that].”

Karabin notes “there was some action” over Italian workers attempting to unionize, “but it was never setting-your-house-on-fire kind of violence.”

That calm continued into World War II, in part because the war meant the embroideries were too busy working for any conflict.

“Immigrants produced a range of products, from luxury laces to military emblems and insignias during World War II,” author Yolanda Prieto wrote on Union City in the first half of the 20th century. “There were also many silk mills and several beer breweries located throughout the city. In time, Union City thrived on commercial activity, and Bergenline Avenue, a central thoroughfare, was bustling with stores, banks, and other businesses.”

Economic downturn – even during the Great Depression – did little to quell social development in the city. Yet, as it often does, culture succeeded where economics failed. By the end of World War II, the “immigrants” of Europe had largely assimilated into American culture. The men had fought in the war and the women raised their children in American schools, engineered to foster a universal domestic identity. New Jersey has always bred a stubborn regional pride, but not at the expense of patriotism.

“The kids really learned that and they learned it in school,” Tonelson, the economist, tells me, recalling the lessons of his father, who grew up in New York.

“He would say over and over again that even when he was going to Kindergarten on his first day of school in 1929,” Tonelson noted, “from the minute he got into that school building, as much as his little five-year-old brain could wrap itself around it, there was no doubt that one of its main missions was teaching him how to become a little American.”

The little Americans starting school in 1929 had tired of city life by 1950. Soldiers returning home from war wanted to marry and start families outside of tenement buildings. They wanted their children to have lawns and dogs and less-crowded public schools. The government, finding an opportunity to create infrastructure development work for the wave of unemployed men flooding the job market, was happy to oblige.

“After World War II, the search for housing space, intensified by a soaring increase in marriages and births and facilitated by home loan guarantee programs of the Veterans Administration, turned the outward drift into a rush,” W.B. Dickinson wrote in 1960, panicked about the collapse of the modern American city. “By 1950, fewer than one-half of the inhabitants of 40 metropolitan areas lived in the central city.”

“[My father] would say over and over again that even when he was going to Kindergarten on his first day of school in 1929, from the minute he got into that school building, as much as his little five-year-old brain could wrap itself around it, there was no doubt that one of its main missions was teaching him how to become a little American.” Alan Tonelson

He went on to note, by 1960, “72 of the 225 central cities in the 189 metropolitan areas [had] lost population, many of them for the first time. Four of the five cities with a million or more of inhabitants—New York, Chicago, Philadelphia, Detroit—are in this group; Los Angeles, which has annexed additional territory in recent years, was the only one of the five to gain population.”

By the end of the 1940s, Union City “was basically a ghost town,” Karabin told me.

“It really left Union City behind. A lot of men coming home from World War II were veterans and first generation children of immigrants. So, say your parents came from Italy or Germany or whatever in the 1900s,” he explained. “You’re the son or grandson and you’re in your 20s. You’ve got your little money from your G.I. Bill and all the suburbs are being built, all these pre-fab houses, and you’re not satisfied anymore living in an apartment or houses that are so bunched together.”

Union City’s population dropped 1.5 percent from 56,173 to 55,322 by the end of the 1940s. In another decade, that number would fall to 52,180.

[1] Wealthy Jersey City residents created associations to combat what they believed was a Catholic invasion of the country in the 1800s. Jersey City media elites lamented that “no Irishman ever died of hard work in America” and Irish incorporation into “Yankee” culture would erode local work ethic. Jersey City ultimately fell into the hands of its most notorious mayor, Frank Hague, in 1917, after he built a political machine out of the growing, and discriminated against, Catholic immigrant population. Hague ruled for 30 years.

COMMENTS