With the summer sales on Steam and Amazon on hundreds of PC games going on right now, I felt it was a perfect time to highlight a number of the most interesting games available for gamers to enjoy this summer. The first title I wanted to examine was one of the most talked-about releases so far this year: BioShock Infinite.

I really didn’t want to review BioShock Infinite.

I knew, in light of my article about the game’s politics before its release, anything negative I had to say about it would quickly be dismissed by its defenders as outraged griping from the token conservative critic. I put it out of my mind after I finished it, but seeing it pop back up on sale from a number of outlets months after its release, combined with continued questions about why there was never a follow up review to my original story prompted me to finally bite the bullet. The fact is, the politics in Infinite represent the smallest problem I have with Irrational Games’ latest effort. Mediocre gameplay, flawed design, and vapid storytelling are what sink the long-awaited followup from Ken Levine and company.

BioShock Infinite is a first-person shooter in which players assume the role of Booker DeWitt, a private investigator hired to infiltrate a flying city, Columbia, that seceded in an alternate universe of America in 1912. Booker is told, “Bring us the girl and wipe away the debt”; the girl is Elizabeth Comstock, the daughter of Zachary Hale Comstock, the fundamentalist leader and “prophet” of Columbia. In addition to finding a city tearing itself along political, social, racial, and ideological battle lines, Booker finds that Elizabeth and her ability to open inter-dimensional tears in the world around her is the key not only to the future of Columbia but his own fate as well. Booker must find a way to get Elizabeth safely out of Columbia as the Founders, the right-wing religious representatives of the status quo, and the Vox Populi, violent leftists revolutionaries tired of the racial and ideological oppression from the Founders, fight for control of the city.

Let’s start with the good: Infinite is a beautiful game. The graphics and audio work present a fantastical but immersive world that, sadly, the rest of the game’s design just can’t match. From the first moment the player breaks through the clouds and sees Columbia’s grandeur under the unfettered sun, while ragtime piano music trills lazily in the background, Infinite presents a stunning sensory package. The warm color schemes, bright environments, and slightly exaggerated character designs create an almost painterly image of turn-of-the-century America. Barbershop quartet renditions of songs well beyond the time of Columbia combined with earnest hymns convey the religious fervor of the citizens, while also hinting that something is very strange with the reality in which the city exists. Solid voice performances round out the package, particularly the work done by the actors for two quick-witted siblings Booker runs into through the game.

Unfortunately, as I said, the rest of Infinite doesn’t live up to game’s wondrous first impression.

It all starts with the most crucial aspect of the game: how it actually plays. Rather than significantly change the gameplay mechanics from the original BioShock, Irrational has merely iterated on their previous game in the series. That wouldn’t seem like the worst thing in the world on paper, as BioShock was a breath of fresh air in the first-person shooter genre when it was released in 2007, but then you realize that was six years ago, and what worked in Rapture doesn’t necessarily work in Columbia.

The dual-wielding gunplay of the original BioShock returns in Infinite, with players sporting firearms in one hand and Vigors in the other. Vigors function similarly to Plasmids in BioShock, granting players powers like lighting enemies on fire, electrocuting them, or tossing them in the air, to name a few. Both weapons and Vigors can be leveled up to deal more damage or provide other improved effects, but there isn’t much new here, with many of the abilities functioning as direct analogues to the powers in the previous game. Worse, some of the skills in Infinite feel unbalanced and, in some cases, downright worthless.

The Possession tonic, for instance, seems like it would be a useful tool, as it allows the player to cause mechanical enemies to fight for them for a period of time and even causes human opponents to turn on their former comrades. Unfortunately, the mechanical enemies that have no problem ventilating the player character struggle to target other enemy NPCs once under your control. Even when fully upgraded, the time period in which some of the more powerful robotic foes remain under the player’s control is so brief that they won’t even fire a shot at Booker’s opponents before the effect wears off and they turn on the player again, accomplishing nothing while robbing you of some of the precious salts that power your Vigors.

The more conventional weapons don’t fare much better, with you standard assortment of pistols, shotguns, rifles, and explosives. None of the weapons feel all that substantive, with little reaction from enemies when shot and floaty, imprecise aiming. The developers try to introduce a little variety by offering different versions of some of the weapon classes used by the Founders and Vox Populi, but the differences don’t amount to much more than different firing speeds or slight changes in damage dealt. Beyond that, the contrasts between the two factions’ weapons are largely cosmetic.

Not helping the lackluster combat is the largely unimpressive enemy artificial intelligence. Enemies will either hide behind the same piece of cover for the entirety of firefights or run straight at the player with murderous abandon. While the enemy AI in the original BioShock wasn’t exactly groundbreaking, the dark, claustrophobic environments in that game played to the enemies’ strengths. Psychotic Splicers bounced off of walls and ceilings to dodge your gunfire or ran around you in the darkness to fire at you while you tried to figure out where they were hiding. Infinite’s large, open-air plazas and grandiose architecture doesn’t allow the AI to exploit the environment in the same way. The much-hyped skyhooks don’t do much to change the dynamic of combat either, as enemies will either stand stock-still on the ground below shooting at you as you zip overhead or jump on the tracks and harmlessly follow you without attacking until you jump off.

Similarly disappointing is the lack of a signature enemy in Infinite to rival the iconic Big Daddy from its precursor. Among the great strengths of BioShock were the intricate combat sandboxes throughout Rapture in which players could experiment with any number of approaches to tackle the combinations of human enemies, security systems, and environmental features they would encounter. Then, when the player believed they had the situation in hand, the developers would drop a bomb in the middle of the proceedings in the form of the Big Daddy. Hulking, forlorn, and terrifying, these gentle giants would ignore the player so long as their wards, the Little Sisters, were left alone. Tromping through levels without regard to the player, all it would take was one errant bullet from a gunfight with Splicers to send a Big Daddy into a murderous rage, forcing the player to adapt in the resulting chaos to have any hope of survival. Conversely, players could plan out battles with the undersea guardians to exploit the environment and/or the patterns of other AI enemies to reap the rewards from defeating BioShock‘s signature foe.

At the same time, Irrational took the time to shape the Big Daddies as not only central to the mechanics of BioShock‘s gameplay but also to the story of the doomed underwater utopia. The forlorn moan of the reluctant antagonists, followed by the heartbroken crying of the little girls they were dutifully protected was a deeply emotional experience for many players. It gave weight to the violence of the game and served as a symbol of the tragedy that had befallen the citizens of Rapture.

Infinite is never able to replicate the same emergent gameplay with the four promoted categories of “Heavy Hitters” you face, nor do they earn the same emotional reaction as the doomed behemoths of Rapture. Columbia’s Motorized Patriot and Handyman are little more than bullet sponges that charge the player head-on. The only tactics necessary for these fights are to run as far away as possible, fire off as many shots and Vigors as you can before they’re able to attack you again, and repeat until the last of their health bar finally ticks away. The Boys of Silence are nothing more than creepy human versions of a security camera, limited to a single level towards the end of the game. Finally, the Siren isn’t a class of enemy at all but rather an individual character that provided the most frustrating and tedious boss fight in recent memory.

Finally, there’s the character of Elizabeth, and it is only fitting that, as the central device of the game’s plot, she should provide the perfect example of both BioShock Infinite‘s gameplay and narrative failings. Billed as an intelligent companion to complement the player throughout the game, Ken Levine stressed before the game’s release that the developers did not want characters to feel as though the entire game was a protracted escort mission. Unfortunately, what they ended up creating was the human equivalent of a power-up dispenser. In combat, enemies will completely ignore Elizabeth so players aren’t forced to protect her, limiting your interaction to little more than pressing the “Use” button to initiate a pre-canned animation of Elizabeth throwing items to you.

Slightly more interesting is Elizabeth’s ability to open tears in reality to provide you with different advantages in combat, spawning weapons, changes in the level geometry, or even AI allies to fight your foes for you. I found the tears were never essential, however, and they ruined the pacing of the game for me. Entering an area to see the distinctive shimmer of potential tears would telegraph the fact that enemies waited in ambush for me to cross an imaginary line and spawn them around me, ruining any tension in the quieter moments over when the next bout of combat would begin.

Outside of combat, Elizabeth will traipse around the environment with a weirdly whimsical skipping animation while randomly “finding” money and other items for Booker that she’ll dutifully toss to him. She can also pick special locks for Booker, behind which the player will usually find more money or upgrades for their abilities.

So Elizabeth doesn’t offer much in the way of meaningful gameplay or interaction, but surely, as a central focus of the game’s plot, she must be a dynamic and engaging character, right? Again, the appeal here only goes skin deep. The designers obviously paid much attention to her character’s modeling and animation to make her seem human and emotive, but Elizabeth never rises beyond the “damsel in distress” trope that the game’s creators seem so desperate to deny she embodies. Booker must rescue her whenever it’s convenient to the plot; she acts emotionally and irrationally when presented with mortal danger just because Booker says or does something that offends her on a number of occasions; and she is never granted an opportunity by the game’s script to be much more than a source of exposition for the more convoluted and nonsensical elements of the story.

That’s Infinite‘s problem as a whole: it pretends to say and do much more than it ever actually achieves. It wants to examine racial and social issues in America, but the way they’re presented are so over-the-top that it’s impossible to take the game seriously. Towards the beginning of the game, a seemingly idyllic festival celebrating the anniversary of Columbia’s founding turns cartoonish when the player is forced to choose between participating in or intervening in the assault on an interracial couple–the premier event of the festivities. Later, players will make their way through buildings in which signs proclaim, “Protecting Our Race,” and paintings depict Abraham Lincoln as the devil.

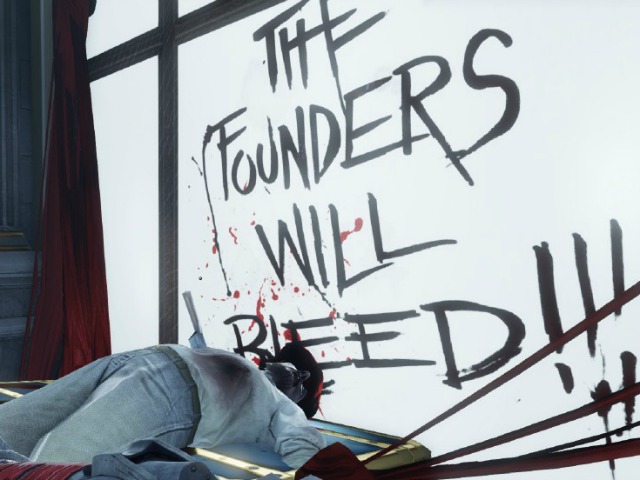

Progressives get much the same outlandish derision heaped their way, with the Vox Populi depicted as murderous Reign of Terror-style revolutionaries who torture and taunt the upper-class Columbians before killing them out of some twisted sense of social justice. It’s all rather silly, and it seems Levine has nothing of substance to say about the competing ideologies of Columbia (and, as a result, America). The only position that he seems to take is that ever taking a stand on an issue means you are or will soon become a dangerous extremist. Hammering that point home is Booker’s refusal to take a side in the conflict, acting as a disinterested interloper between the two factions–only concerned with doing his job and saving his own skin.

So BioShock Inifinite appears to refuse to take a stance on any of the social or political issues it purports to examine–that is, until the last ten minutes of the game. At this time, Ken Levine makes his personal opinion on one issue very clear: religion appeals only to the emotionally scarred and mentally weak and gives them license to commit terrible atrocities in the name of their faith. Moreover, it’s hard to take away anything more from the game’s contrived ending than that Levine is arguing the world would be a better place if followers of any and all faiths didn’t exist at all.

The ending is particularly jarring, as a game whose only discernible message for 99% of the play time is that extremism in all forms is dangerous essentially tells the religious player, “Go kill yourself,” right before the credits roll. This isn’t a serious exchange of ideas; this is 4chan trolling. Worse, it highlights how everything that came before it was absolutely meaningless and served only as a means to pull you along with the hope of some narrative payoff, only for Levine’s bait-and-switch at the end so he can preach to a captive audience that has invested too much time to turn away from his vitriol.

Between the final sucker-punch and the tedious nihilism preceding it, the real travesty of Infinite’s story is the deference it has been afforded since the game’s release. If this is truly the best that game makers can do in terms of storytelling (as many others have claimed), then we still have a long way to go. Infinite is junk philosophy, dressed up in manufactured controversy to sell an ostensibly deeper story to the Call of Duty crowd without possessing the smallest scrap more of narrative maturity.

Unfortunately, much as Activision’s juggernaut shooter series has shaped the rest of the gaming industry, Infinite is sure to spawn a generation of pseudo-philosophers hoping that they too can get away with mediocre game design disguised by faltering pretentions at social commentary. As competitors have attempted to imitate Call of Duty in hopes of garnering the same commercial and critical success, BioShock Infinite‘s shallow, banal storytelling will undoubtedly set the narrative standard for years to come.

If the gaming industry wants to be viewed as a legitimate art form by the outside observer, then the community needs to be unafraid to call out drivel like BioShock Infinite for its glaring missteps. If we continue to prop up games like this simply because we believe it represents the last best hope of convincing the uninformed outsider of the medium’s worth, we’ll never move beyond artistic depth that is only skin deep. Infinite is unquestionably pretty to look at and appears to offer a mature examination of hot-button social and political topics at first blush, but beneath that veneer is a dull core of focus-tested shooter-bro insipidness.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.