Best-selling author Bernard Cornwell, whose Saxon Tales series of historical fiction books was recently made into the BBC’s The Last Kingdom, tells Breitbart News in an exclusive interview “we absolutely can” trace the origins of Anglo-American concepts of constitutional liberty, individual rights, and the rule of law to Alfred the Great’s obsession with justice and the development of a written legal code.

“The big story behind [my Saxon Tales series] is actually the making of England,” Cornwell says.

“I realized a long time ago that I didn’t know where England came from. I had no idea. I mean, I’m an American citizen now. We all know where America came from. We actually have a birth day. We can celebrate it. That’s great. We have parades and balloons and fireworks,” he adds.

“England, the assumption is, has always been there. That’s simply not true,” Cornwell notes.

“When [the Saxon Tales series begins in the 9th century], there’s no such thing as England and then forty years later suddenly there is something called England. The books are telling that story,” he says.

“The war that makes England is partly a tribal war, of course. Us against them, Saxons against the Norsemen. But it is given an added spice by religion. There’s no doubt that Alfred [the Great] (born, 849 A.D., died 899 A.D., King of Wessex 871 to 899) – it was his dream [to create a united England]. He was an extraordinarily pious man,” he notes.

“He’s an incredibly intelligent man. A deep, intelligent man. But he’s also a very, very committed Christian,” Cornwell says of Alfred the Great.

“Alfred took the view that you can kill the pagans, because we’re doing God’s work in driving them from the country, but if, in fact, a Dane converted to Christianity then they immediately ceased to be an enemy,” he notes.

“It seems to me in many ways the religious side triumphs over the political issues. Truth to tell, in that era, religion was political, and stayed so for many, many, many centuries,” Cornwell says.

“And it is an extraordinary story. At one point [during Alfred’s reign], the Saxons are pinned back to the Somerset marshes. The Danes controlled more or less all of what was to become England. And at that point you say, we wouldn’t be having this conversation in English, we would be having it in Danish. I mean, all of history is going to change if it wasn’t for Alfred breaking out and winning the Battle of Ethandun. “

The Germanic tribes that invaded England in the fifth and sixth centuries—the Angles and the Saxons “seemed to have a respect for the individual’s freedom, even though there is slavery and though there is a severe gradation, a hierarchy. Nevertheless, there are witenagemots,” Cornwell observes. The witenagemot was an early ruling council of lords who selected and advised kings, a precursor to the English Parliament.

“I think the New England town meeting is a direct descendant of how the Saxons governed themselves,” says the English born and raised, Cornwell, who now lives part of each year in Cape Cod.

The rule of law is also firmly rooted in these Anglo-Saxon traditions of governance, Cornwell observes, noting that “trial by jury is Saxon.”

“This goes underground in a way once the Normans are in England, but it comes back,” Cornwell says. Concepts of individual liberty and rights that came from the Anglo-Saxon heritage were dramatically diminished when the Normans, led by William the Conqueror, conquered England at the Battle of Hastings in 1066.

“There was really a resurgence of [these Saxon] English institutions during the Hundred Years War,” he adds. The Hundred Years war was a long series of battles been England and France that began in 1337 and ended in 1453. Cornwell has written several historical novels set during that period, the most recent of which is 1356: A Novel.

The phrase “the Norman yoke,” first gained popularity in England in the early 17th century when John Lilburne argued that the tyrannical “absolute monarchy” of the Stuart kings had its origin in royal system imposed by the Normans at the expense of the more limited “pre-constitutional monarchy” of the Anglo-Saxon system.

The same term was used by Thomas Jefferson and James Otis at the dawn of the American Revolution to describe the tyrannical excesses of George III.

Cornwell notes that he is quite familiar with the “Norman yoke” phrase, as were the members of the Continental Congress.

“Yes, I have, indeed [heard of the “Norman yoke”]. And interestingly enough, the very first warship that was commissioned by the Continental Congress was called the Alfred – deliberately,” Cornwell adds, a fact that was recorded by John Adams, “one of the members of the Naval Committee,” in the Diary and Autobiography of John Adams, Volume 3.

The ship, built as a merchant vessel named The Black Prince a few years earlier, was purchased by the Continental Congress in 1774 and in 1775 was “[r]enamed Alfred, after the ninth-century West Saxon king who had founded the English navy,’the finest ship . . . in America’ soon became the first flagship in the United States navy,” as John J. McCusker wrote in his book Alfred: The First Continental Flagship, 1775-1778, published by the Smithsonian Institution Press in 1973.

Cornwell, was born in England in 1944, and came to the United States for love without a job or a work permit when he married his American wife in 1980.

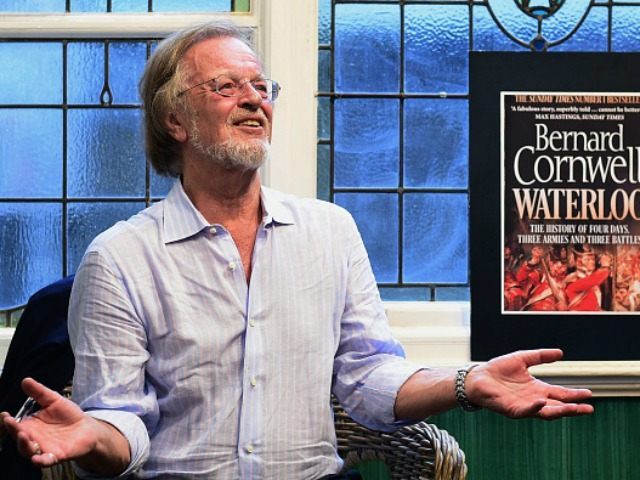

Since then, he has written over 50 books of historical fiction, which have sold an estimated 30 million copies. His only work of non-fiction—Waterloo: The History of Four Days, Three Armies, and Three Battles—was published in 2015 to excellent reviews around the world and number one best-seller status in Britain.

You can read the transcript of the Breitbart News Interview here:

QUESTION: You said in a video interview posted on your website that the key to writing historical fiction is to take a big story that has a little story within it, and then. flip them. Make the little story the one you’re telling, with the big story as the backdrop. You cited Gone With the Wind as an excellent example of that.

In the Saxon Tales series, is Uhtred, the Saxon warrior and protaganist, Scarlett O’Hara with a sword?

CORNWELL: Yes he is. There’s a back story to that, which was that I was adopted. My biological father was a Canadian Airman who served in England during World War II. My biological mother was English.

His name was Oughtred. He was living very happily on Vancouver Island. I met him for the first time when I was 58, and he showed me the family tree. It went all the way back to the 6th century. There were a whole bunch of names U H T R E D. This name has come down through 1400, 1500 years, and it turned into OUGHTRED. The family tree checked out. I suddenly realized that I had this ancestor who lived at Bebbanburg, Bamburgh Castle, all those many years ago. I knew nothing about him because I think there’s one signature on a charter, and I thought, “how the hell did they hang on to that land?” when they were surrounded by Vikings and Danes, and that became the little story.

QUESTION: That was with your biological father?

CORNWELL: Yes, who of course I had never met until that point. I was 58 then I think.

QUESTION: How did that meeting come about?

CORNWELL: I was being interviewed by some very nice man from the Vancouver Sun. It was pretty obvious that his editor had said there’s this author and I want you to go interview him, and he was plainly bored to death. I had always known my real father’s name and I had known he had come from somewhere in the Vancouver region. He had been in the Royal Canadian Air Force in Britain in the second World War. I proceeded to tell the reporter the story. I didn’t give him the full name, I just gave him the surname. Two days later a young woman came up and said “I think I’m one of your cousins.”

And she gave me William’s, my father’s address. So I wrote him. He’s dead now, sadly, but we had many happy meetings after that.

QUESTION: I imagine that personally you had some very mixed emotions about that.

CORNWELL: Not particularly. I got to the point where I was curious about him, obviously, but I didn’t need a father…Obviously I was terribly curious, and he was the only person who could tell me anything about my mother. As it turned out it was a very happy meeting, and we became fast friends of the family, and I found I had two half-brothers and a half-sister, who are all still living in Vancouver or Vancouver Island.

QUESTION: Did the nature of your birth and adoption color your writing in the Saxon tales a bit? I see a lot of illegitimate children or half brothers half sisters and you seem to write those characters with a great deal of empathy

CORNWELL: I’m not aware of it. I think probably the biggest effect it had on me is I was adopted by a rather strange family, who belonged to a sect called the Peculiar People. And they were, by God. I think probably that adoption had a huge effect on my life in the end, not necessarily a particularly good one.

QUESTION: Were they fundamentalist Christians?

CORNWELL: Fundamentalist, evangelical with an enormous list of things that were forbidden, of which among were novels, which I now write, television, which I joined happily, military service, cosmetics, alcohol, Roman Catholics, films, cinema, theater. I think it was Mencken who gave his definition of a Puritan as someone who is haunted by the fear that someone somewhere might be happy.

QUESTION: I notice in your writing how Uhtred views Christianity.

CORNWELL: He has fun with it, doesn’t he?

Yes, it is definitely part of that story. The war that makes England is partly a tribal war, of course. Us agains them, Saxons against the Norsemen. But it is given an added spice by religion. There’s no doubt that Alfred [the Great] (born, 849 A.D., died 899 A.D., King of Wessex 871 to 899) – it was his dream [to create a united England]. He was an extraordinarily pious man. We know that from his own writings. We know that from Bishop Asser’s biography of him.

He’s an incredibly intelligent man. A deep, intelligent man. But he’s also a very, very commited Christian.

That also applies to his daughter Aethelflaed (circa 870 to 918, ruler of Mercia, 911 to 918) , though I stress it less with her, and certainly to his grandson Athelstan ( circa 894 to 939, King of Wessex 924 to 927, King of the English from 927 to 939, and the first king of all England, 934 to 939).

Alfred took the view that you can kill the pagans, because we’re doing God’s work in driving them from the country, but if, in fact, a Dane converted to Christianity then they immediately ceased to be an enemy.

It seems to me in many ways the religious side triumphs over the political issues. Truth to tell, in that era, religion was political, and stayed so for many many many centuries.

QUESTION: It’s ironic you ended up living in Cape Cod [Massachusetts].

CORNWELL: We live there in the summer. The rest of the time we live in Charleston, [South Carolina].

QUESTION: What a great combination. What a great place Charleston is. Have you visited the grave of John C. Calhoun yet?

CORNWELL: I have. I love Charleston. I really love it. I’ve lived here in America now for 36 years. I never felt wholly home until I found Charleston.

QUESTION: Ironically, Cape Code [where you first lived full time when you came to America] was part of the old Plymouth Colony [from 1620 to 1693, when it became part of the Massachusetts Bay Colony]. Not exactly Puritan, but pretty darn close.

CORNWELL: Oh it’s still there. I’ve lived in countries … one of the great blessings about England is it was never Presbyterian. I spent three and a half years living in Northern Ireland among the Presbyterians, and now on Cape Cod [and Charleston].

QUESTION: Your personal story is very interesting. You came to the United States in 1980 for love, you married an American woman.

CORNWELL: Still married to her.

QUESTION: So you left your job at the BBC, you moved to Cape Cod, and you said you began writing novels because the American government would not give you a work permit.

CORNWELL: It’s true.

QUESTION: Can you describe that time for us, particularly your decision to move to the U.S., your realization you wouldn’t get a work permit, and I’m guessing you said to yourself the only thing I could really do here is write novels. When did that become successful enough for you that you could make a living it it?

CORNWELL: I was terribly lucky. What you described is exactly what happened.

I always had a big ambition to be a novelist, and also thought that would be that would be [ a natural] as a journalist, at least I worked in news and current affairs for the BBC and The Thames Television ( a regional franchise of the Independent Television Network in the United Kingdom that operated from 1968 to 1992).

I’m sure you find this true. Lots of journalists think they want to be a novelist. And I was just one of them.

But I never tried it. I never tried to write a novel. It was just one of those very dreams that you hold in your head.

Only when I met Judy and couldn’t get a work permit I thought, well, what the hell can I do?

And I thought, well, why don’t we try?

And it really was just that. I look back on it and it was a crazy decision. I remember saying to her, “Don’t worry darling, I’m going to write a novel.”

I was incredibly lucky. I found an agent very quickly and he found me a publisher. I still have the same agent, same wife, and the same publisher.

I think within a year of making that decision I had a seven book contract.

QUESTION: Was this the Richard Sharpe series, based on the career of a fictional British Army officer during the Napoleonic Wars?

CORNWELL: Yes.

I’m with Harper Collins, who’ve stayed my publisher ever since.

I’ve only written one non-fiction book.

QUESTION: Waterloo: The History of Four Days, Three Armies, and Three Battles, which received extraordinary reviews.

CORNWELL: It did extraordinarily well. It was a best selling history book in Britain last year:

QUESTION: I gather that may be the only non-fiction book you intend to write.

CORNWELL: It’s the only one I really wanted to write, so I suspect it is the only one.

I always wanted to write that one, because it’s such a compelling story. And with the bicentenarry coming up, it seemed an obvious thing to do.

But it was so different than writing fiction. It is with great relief that I’ve gone back to writing fiction.

QUESTION: And the Richard Sharpe series is set in that time period, so you’re familiar with it.

CORNWELL: I thought I was very familiar with it, and I was entirely shocked in writing it — and I enjoyed writing it – was to find out how much I didn’t know, and how much more research was needed.

I think that’s probably the right reaction to have.

Yes, I knew a helluva lot about the Peninsula War, about Waterloo, about Wellington, about Napoleon. Then you actually come to write the book and you realize you don’t know nearly enough.

QUESTION: How did that June 2015 New York Times Op-ed , “The Waterloo They Remembered,” come about?

CORNWELL: I got phoned up by someone at the New York Times, a rather charming man. I had forgotten about that entirely. They asked me.

QUESTION: It struck me as interesting because — and maybe I read it wrong — it came out in the last paragraph that you had a wistful hope for peace instead of war. That seems a little different from the themes of the Saxon Tales.

CORNWELL: It probably is. I had completely forgotten that piece. I think there was a felling, certainly in London – we went to London for the commemoration service for Waterloo — that it was the time for reconciliation, not for gloating or triumphalism, so I’m sure I was slightly effected by that.

QUESTION: Uhtred’s voice [in the Saxon Tales], a very strong voice, clearly was involved in non-stop war. His view might be seen as generally, the old Roman maxim, if you want peace, prepare for war. Be ready to conduct war. That seems to be Uhtred’s overall view.

CORNWELL: Yes, and Uhtred lives in an incredibly violent age. One of the most surprising things, if you grow up in England as I did, you tend to think of it as rather a peaceful country. The last battle, the Battle of Sedgemore, in what, 1674 or something, not counting the Battle of Britain [during World War II where Germans bombed England] or something. [Sedgemore was ] the last actual battle on English soil. that was fought on English soil.

It is a peaceful countryside. You drive out in the countryside and it looks peaceful. The very first big country houses that were not crenelated (built with battlements that contain merlons–upright sections–separated by crenels, or open spaces, where defenders could position themselves) and built for defense were built in England because on the whole it was a very peaceful society.

Then when you read the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle and the other chronicles, you see, my God, there were battles in Surrey. I mean, they don’t have battles in Surrey!

And it is an extraordinary story. At one point [during Alfred’s reign], the Saxons are pinned back to the Somerset marshes. The Danes controlled more or less all of what was to become England. And at that point you say, we wouldn’t be having this conversation in English, we would be having it in Danish. I mean, all of history is going to change if it wasn’t for Alfred. If it wasn’t for Alfred breaking out and winning the Battle of Ethandon.

It is an extraordinary story, but it’s an incredibly bloody story.

If you read their poetry, you realize that what they celebrate is two things. They celebrate Christianity, which is the dream at the root, and they celebrate battle.

Alfred recognized that he needed people like Uhtred. He needed these linebackers in mail and steel who would go and fight the Vikings and fight the Danes.

If you’re in that situation, like Uhtred is, then yes, you’re going to be beligerent, you’re going to be good at war.

QUESTION: There’s so much blood and gore, how do you write that in a way that it doesn’t become repetitive?

CORNWELL: I wish I knew. [laughter] I suppose that it’s the context of each fight is important, very important. And what’s at stake. Each one has slightly different characters.

QUESTION: I have a question about the Saxon Tales. I’m looking at history, and it seems to me you can take these tales all the way up to and a little bit past the near 20 year reign of King Canute (1016-1035) ?

CORNWELL: I could. I think the big story behind this is actually the making of England. I realized a long time ago that I didn’t know where the hell England came from. I had no idea. I mean, I’m an American citizen now. We all know where America came from. We actually have a birth day. We can celebrate it. That’s great. We have parades and balloons and fireworks.

England, the assumption is, has always been there. That’s simply not true.

When [the series begins], there’s no such thing as England and then forty years later suddenly there is something called England.

The books are telling that story.

For me, the final point – the trouble is that Uhtred is going to be so damn old I’m not quite sure how I’m going to cope with it — is a thing called the Battle of Brunanburh (934). Brunanburh is where King Athelstan (Alfred’s grandson) defeats the Scots, the Kingdom of York, the Norsemen from Ireland, the whole damn lot that gang up against him.

It was obviously an enormous victory. One of the strange things is we still don’t know where exactly it happened.

The Chronicles tell us some stuff about it. Some hint that it was a siege, though that seems unlikely but it might have been. One says seven kings died on that battlefield. Whatever it was, it was a huge victory. At the end of it, Athelstan is acknowledged as King of all England, or “Englaland.”

They were actually to lose some territory later on, and it was the Danes, eventually, under Canute, who were going to take the whole thing back [temporarily], but that’s the moment when England becomes one country.

Whatever happened to it afterwards, doesn’t matter. It is now established, and it’s there. It will recover and it will go on.

So for me, Brunanburh is really the making of England, and the whole series leads up, eventually, to that battle.

QUESTION: By that time, Uhtred will be about 78-years-old I think.

CORNWELL: Don’t tell me, I know!

QUESTION: I don’t know if a 78-year-old guy can fight these kind of battles.

CORNWELL: But he can be there, but not fight.

I’m sort of writing up Athelstan in more recent books. I’m not sure whether I will change to his voice, whether I’ll use Uhtred sans voice, whether I’ll keep Uhtred’s voice. The book I’m writing right now is where Uhtred recaptures Bebbanburg, which is one of the major stories in the whole thing. And it’s going to be interesting to see what happens when you’ve done that, whether he and me lose enthusiasm.

I think not, because actually Athelstan’s story becomes so compelling. I might make up a new character altogether but still keep Uhtred in the background.

QUESTION: You certainly have done a terrific job of connecting Uhtred to Athelstan.

CORNWELL: I can imagine him [Uhtred] at Brunanburh as a rather grumpy old man on horseback giving advice.

QUESTION: What’s your writing process?

CORNWELL: I would like to say wonderfully organized, but it’s probably rather haphazard. I get up in the morning early and I sit at the desk here and I keep going, and then I take the dog for a walk and I read the newspaper and I do whatever. But it gets done somehow.

There is no other way except to sit down and do it. I’ve never believed in writer’s block.

Maybe if you’re a genius and writing novels of the human soul, which are incredibly tricky and difficult.

The only people other than that who are allowed to have writer’s block are brand new writers who have never written before, who lack the confidence, and that will certainly block you.

But the day that a nurse can phone the hospital and say “I can’t come to nurse, I’ve got nurse’s block,” and they say “oh no dear, you mustn’t come in, you must stay at home,” is the day I’ll believe in writer’s block.

QUESTION: You’ve written, I think it is, I counted over 50 books.

CORNWELL: It is. I’ve lost count,too. It’s like 52 or 53.

QUESTION: How many books have you sold?

CORNWELL: Millions. I don’t know what the figure is. My agent claims 30 million. I have no idea if that’s true.

I’ve been very, very fortunate. I’ve been a regular best-seller in Britain. Germany, Brazil, for some reason. I don’t know why, but I love them. Scandinavia. Done less well in the USA, but that’s fine. Judy and I are not suffering.

QUESTION: I think that as Americans come to learn of your work, your sales will increasingly increase here.

CORNWELL: Well, why should you? It’s not your history.

QUESTION: I beg to differ. It absolutely is our history.

CORNWELL: I actually agree with you. It is your history. It’s one root of the tree, it’s not the tap root.

QUESTION: I’m not quite so sure about that. I think it’s a continuum.

CORNWELL: We probably agree on that, but I’m trying to find good reason why people [in the US) shouldn’t …it’s not compulsory they should read me.

QUESTION: That’s a good segue to the political questions. You can put your dancing shoes on now. These are questions that reflect my personal world view and I think would be the world view of many of our Breitbart readers. I’m trying to give our readers a connection between the world view we have and the books you’re writing.

CORNWELL: Right

QUESTION: First question: Would you agree with my view that you can trace the origins of Anglo-American concepts of constitutional liberty, individual rights, and the rule of law, to Alfred the Great’s obsession with justice and the development of a written legal code?

CORNWELL: Yes, I think you can. I think you can certainly trace it beyond that even, to the Germanic tribes [that invaded England in the 4th through 6th centuries]. They seemed to have a respect for the individual’s freedom, even though there is slavery and though there is a severe gradation, a hierarchy. Nevertheless, there are witanagemoots (early versions of ruling councils that evolved into Parliament centuries later), there are … I think the New England town meeting is a direct descendant of how the Saxons governed themselves.

This goes underground in a way once the Normans are in England (after the Battle of Hastings in 1066), but it comes back.

Trial by jury is Saxon.

QUESTION: What first clued me in to this was the use of the phrase “the Norman yoke” by Jefferson and others. Have you heard that phrase before?

CORNWELL: Yes, I have, indeed. And interestingly enough, the very first warship that was commissioned by the Continental Congress was called the Alfred — deliberately.

QUESTION: All of these concepts of individual liberty and rights that came from the Anglo-Saxon side of things were really diminished when William the Conqueror and the Normans won in 1066.

CORNWELL: There was really a resurgence of English institutions during the Hundred Years War.

QUESTION: Second question: My view is that much of the population and leadership of England and the United Kingdom have lost an understanding of their own heritage. In particular, their long tradition of sovereignty, constitutional liberty, and the rule of law. This seems most notable since the departure of Margaret Thatcher from the political scene.

CORNWELL: Listen to G.K. Chesterton. “We are the people of England, and we have not spoken yet.”

I’m not sure you’re right. I would agree that maybe that concept is misted, by all sorts of things.

I think the English have a very good sense of who they are.

I haven’t lived there for thirty-something years, but obviously I take a big big interest.

They don’t shout about it very loudly.

But I actually think they do have it, they know who they are.

This leads on to a whole wealth of other areas which I suspect you might be going to. . .

I can go further.

QUESTION: Yes, sure.

CORNWELL: Am I worried about Islamic extremism? Yes. Like hell I am.

And you can take these even broader because one of the things Uhtred, God bless him, dislikes about Christianity [of his era] is that it is monotheism. One of the distinguishing things of monotheism is it says I’m right and you’re wrong. And there’s absolutely no compromise.

Christianity in many ways has moved way, way, way beyond that.

My wife is an Episcopalian. I speak with knowledge.

But Islam hasn’t.

And it is this rigidity of any fundamentalist belief which is so worrying.

I find it worrying that anybody says “I am 100 percent right, and anyone who disagrees with me is 100 percent wrong.”

What was it that Cromwell said? “I beseech you, in the bowels of Christ, think it possible you may be mistaken.” [In a letter written in 1650 to the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland.]

I think whatever opinions we have, and I hold many opinions very firmly, I like to think I am always at the ready at least to examine them and see well, am I right, am I wrong?

I think once you inject this kind of fundamentalism into the body politic, it makes life very difficult, because it’s so difficult to reach a compromise, reach an agreement.

I think there is a way out of it.

I was in Manchester a couple of years back and went out of the restaurant to have a smoke, I’m a sinner.

A double decker bus went past. This was about 10 o clock at night.

I was this lone male standing on the pavement.

It was absolutely full of chicks, who all cheered me like crazy.

The lights were on in the bus. It was a private bus, a pre-wedding thing.

And what I noticed was that it was almost 50-50, Asian and white.

And they were having a terrific time.

They gave me a terrific time. They gave me a terrific time, gave my ego a huge boost.

I thought, ok. Assimilation is happening.

I have great faith in Western Civilization, in the attractions of Western Civilization, in the liberties that we have, in the freedoms that we have.

Which isn’t to say that there are not going to be defective people, who are going to hate us for that. Who are going to feel left out. Who are going to try and hurt us and do incredibly evil things.

I do think that the second and third generation of these people going out in Western society, more than we know will in fact be drawn to our way of life rather than their own.

I could be entirely wrong. I have no sociological data to back that up, I just have a glimpse of a bus full of very pretty young girls.

QUESTION: Richard Koch, an entrepreneur from the UK who lives in Gibraltar, or somewhere nearby in Portugal, says there are six reasons for the rise of Western Civilization. One of those six has been the spread of Christianity.

CORNWELL: I wouldn’t disagree.

QUESTION: Clearly, Uhtred almost has a begrudgingly similar view. At least in his admiration for Alfred (whom he does not like) for his devotion to the rule of law. Looking at England now, it appears to me that the Anglican Church is in utter decline,

CORNWELL: I suspect you’re right, but again, I don’t know anything about it. It is presumably a decline from a very high point. I guess it’s been in decline ever since Charles II came back probably (after Cromwell, during the restoration of 1661). There’s a good man. The only decent Stuart.

What did Voltaire call England, “the land without God?”

I don’t think religion … Brits aren’t terribly religious, to be honest.

QUESTION: It strikes me that the Christians, like Cromwell, make a huge mistake when they put the church and state together and develop a theocracy.

CORNWELL: Well, the church and state were together already, remember, under the Henriquian settlement. My heroine is Elizabeth I, who started by saying I don’t want windows into men’s souls. She was a very tolerant woman. But she was forced into an extreme anti-Catholic stance, really by the pope, who issued a bull that any Catholic who killed her would be spared purgatory, and by various Catholic conspiracies.

Cromwell, I think what was interesting there is the English Parliament needed the help of the Scots. The Scottish demand then was Presbyterianism. They’re kill joys. They’re terrible kill joys. And the fun prevention league took over for 15 years. I have an ancestor, another of the Oughtreds, they say he invented the slide rule. I have no idea if it’s true, but he was a professor of mathematics at Cambridge University, which is a gene that hasn’t come down to me.

It’s said that he died of joy at the restoration of Charles II.

There was this enormous sense of relief. We get the restoration drama. Indeed, the next amount of sinful corruption, which in turn leads very much to the American Revolution–one strand that leads to it.

Undoubtedly, the English experience of having Presbyterians rule them –when the theaters are closed and the maypole is banished–and people look back and said that a “Merry England” is dead, that has had an effect on the English soul.

QUESTION: During that period, the one character that I found most compelling was John Lilburne. I don’t know if you’ve followed Lilburne and the Levellers during that period.

CORNWELL: I did follow the Levellers. I don’t know that much about Lilburne, but the Levellers I’m more than familiar with. I’ve been to Putney Church, where they were shot.

They’re an interesting group. My view on this, incredibly, we have a neighbor here who’s terribly proud of the fact that she’s descended from people who came over on the Mayflower. I said I’m proud of the fact I’m descended from the people who threw them out.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.