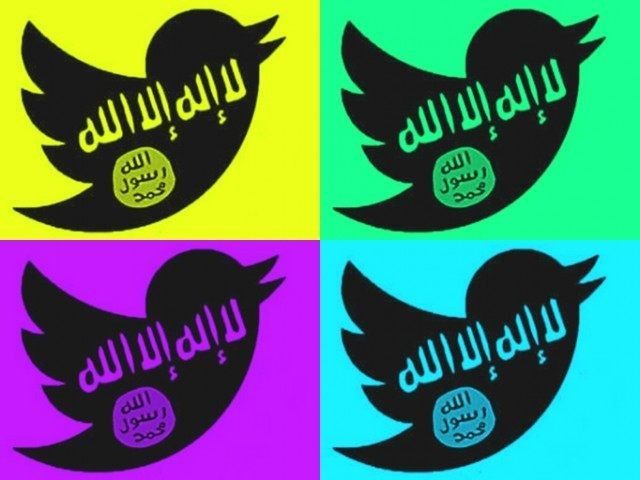

Twitter has struggled to shut down accounts expressing support for Islamic State and other terrorist groups, relying on internet vigilantes like Anonymous to report ISIS-affiliated accounts for suspension. Yet when it comes to suspending critics of feminists and progressives, the social media company has been remarkably proactive.

Over the past few years, the suspensions of critics of feminism and progressivism on Twitter has become increasingly egregious. Janet Bloomfield, the founder of the #WomenAgainstFeminism hashtag, was banned for repeating the words of Guardian columnist Jessica Valenti back to her.

GotNews founder Chuck C. Johnson, who relied on Twitter for his crowdfunded model of journalism, was permanently banned for promising to “take out” Black Lives Matter activist Deray Mckesson with an investigative report. Twitter seized on the ambiguous metaphor as an excuse to ban the polarizing journalist, accepting Mckesson’s spurious claim that it was a violent threat. Even Slate’s Amanda Hess expressed concern at Twitter’s double standards.

Twitter even institutionalised its political favoritism. In late 2014, Twitter announced a months-long partnership with the left-wing feminist group Women, Action and the Media (WAM) to investigate “gender-based harassment” on the platform. The group, which publishes complaints about the media being “very white, very male, very straight” was given clearance to “escalate reports to Twitter.” Politically moderate observers such as Andrew Sullivan drew attention to the brazen ideological bias, but there was no response from Twitter.

Twitter’s behaviour makes more sense when placed in the context of the times. These suspensions occurred at a time when moral panic about trolls, cyberbullying, and the “online harassment of women” was high on the media and political agenda. The British Prime Minister was calling for boycotts against websites that enabled cyberbullying, people were being arrested for sending fake threats to feminists, and the online mockery of feminist vloggers attracted coverage in the national media.

But Twitter is selective about the political firestorms it bends to. Public concern about Islamic State is considerably higher than public concern about the trolling of feminists ever was, yet Twitter’s response to the presence of ISIS sympathizers on the platform has been markedly less enthusiastic.

Twitter cannot plead ignorance about the presence of ISIS on its platform. In March, a report from the Brookings Institution estimated that there were close to 50,000 pro-ISIS accounts on Twitter, with an upper estimate of 90,000. Nor can it say that ISIS is not making effective use of its platform: a more recent report has highlighted in great detail how the terrorist group uses Twitter to radicalize and recruit new members.

Twitter has gone as far as to develop “troll filters” to protect verified users from having their feelings hurt, yet when it comes to tackling the presence of ISIS on its platform, it’s outside groups like Anonymous that have taken up the task of tracking down and reporting ISIS-affiliated accounts.

Twitter says it is making an effort. A spokesman told the Daily Dot that the company has been “working to eliminate any ISIS support on its network.” But their efforts are not paying off: further research from Brookings found that by March 2015, Twitter had only succeeded in suspending a few thousand accounts.

Tellingly, the Twitter spokesman also revealed that the company is still relying on outside reports to decide who to suspend. There was no mention of proactive attempts to detect ISIS on their platform. Twitter will develop a filter to detect and hide mean words, but there are no signs of similar measures to detect ISIS. Instead, it’s unpaid members of Anonymous, working on their own time, who are developing tools to track and report ISIS.

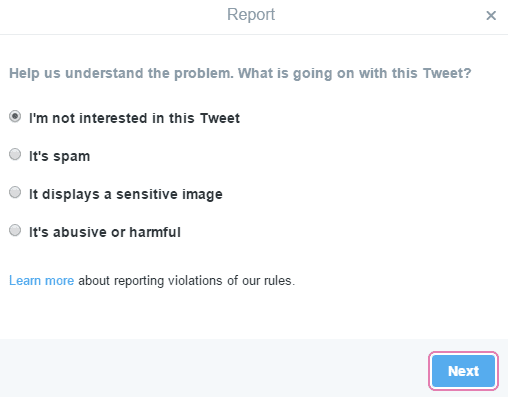

Twitter isn’t even making an effort to make it easier for users to report ISIS accounts. The site has an option for reporting “uninteresting” tweets. “Abusive and harmful” posts can now also be reported, thanks to feminist pressure. But there’s no standalone option for reporting terrorist recruitment. It speaks volumes about Twitter’s priorities.

The double standards aren’t just political. They’re commercial as well. Twitter has suspended accounts at the mere hint of copyright infringement. Gawker’s old sports blog was suspended after it posted animated GIFs from an NFL programme. Absurdly, there have even been reports of Twitter suspending users for repeating comedians’ jokes without crediting them. Twitter has also reportedly considered a “purge” of over 10 million accounts posting adult content to satisfy advertisers.

Twitter also cooperates with the Turkish government to shut down accounts that accuse the government of corruption. In the UK, it shut down an account dedicated to archiving deleted tweets from politicians.

Meanwhile, it took public outcry and an appeal from a victim’s family before Twitter removed the Islamic State’s propaganda execution videos.

There is a case to be made that social media platforms should be neutral communications platforms, that take no position on the content posted by their users and allow individuals to choose their own level of blocking and filtering. But that is not Twitter’s position. The company is perfectly willing to aggressively track down and suspend accounts when it wants to.

And when does it want to? When influential and fashionable political movements have to deal with troublesome critics. When comedians and sports channels with large followings see a glimmer of copyright infringement. When governments and politicians are unhappy with their critics. Meanwhile, tens of thousands of terrorists and terrorist supporters tweet freely.

Follow Allum Bokhari @LibertarianBlue on Twitter, and download Milo Alert! for Android to be kept up to date on his latest articles.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.