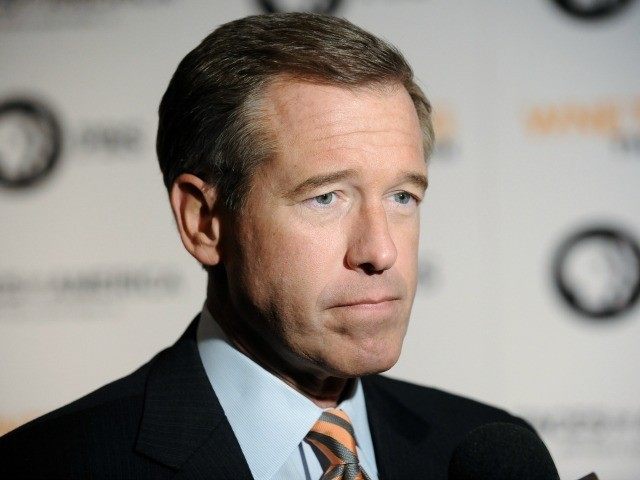

The flaw of Brian Williams, and of most of the press that “gets ahead” in their profession, is that they see gut wrenching, often heroic, activity, and they want to be heroes going through sacrifices in the story as well, but without actually getting involved. But by attempting this action, they alter the real story.

As one sees all of the clips from Williams reporting on himself as a teenage fireman, being shot at in war zones, and in the midst of Hurricane Katrina, he wanted show how he was affected, more so than those truly at risk. When it became about him, and not about what he was reporting, he was lost, and this behavior, like most tragedies, would only increase until he was caught. If the press weren’t like this as well, he would have been caught sooner, but as this was considered almost natural puffery, until someone with real moral authority outside the profession objected, he got a pass.

In this substitution, the press wants to be the heroes, and the real heroes shift to backdrop—supporting actors. Williams wanted us to see him looking down the barrel of some gang member’s gun, the barrel of an RPG launcher (a comedic visual), and have us know he sacrificed by getting physically sick in New Orleans. This obvious common thread — that he is a hero too — pushes out and changes the real story. This effect of making himself the news rather than the news itself is a variation of the “observer effect,” often confused with the Heisenberg uncertainty principle in science, whereby observing some phenomenon, one alters what he is trying to observe. In science there is an attempt to minimize this effect; in the press, it often appears to be the reverse. Thus it is not surprising that Brian Williams occurred and why so many in the press lament his falling, as their path to celebrity status might be at risk if they put themselves in the background to the real news—as they should.

And yet when the press is needed to truly step up and be heroic or courageous, the majority often sidesteps the risk. This was shown after the Charlie Hebdo shooting when the majority of press outlets were cowed into not showing the cartoons that caused the Islamic terror in France. If they had all shown these cartoons, they would have demonstrated a common courage to not be pushed around.

Instead they blinked.

We also see this when the press won’t be truly courageous, and tackle the real injustices because it goes against the status quo. This is where the press could be hugely heroic: exposing wrongs of those entrenched in power.

But they blink.

Instead they go after easier prey.

There is another reason why the press or anyone else inserting themselves into the forefront is dangerous. It was observed and avoided by a famous South Pacific WWII combat fleet commander Admiral Raymond Spruance.

Spruance was an entirely different personality from Halsey, for example; and although on the surface he seemed to be much more like Nimitz; he was sterner, more intellectual perhaps, and far more introverted. If he had his way, the correspondents would not have been allowed hammock room on his ships, and he very seldom would meet with the press. Spruance expressed his attitude:

Personal publicity in a war can be a drawback because it may affect a man’s thinking. A commander may not have sought it; it may have been forced upon him by zealous subordinates or imaginative war correspondents. Once started, however, it is hard to keep in check. In the early days of a war when little about the various commanders is known to the public, and some Admiral or General does a good and perhaps spectacular job, he gets a head start in publicity. Anything he does thereafter tends towards greater headline value than the same thing done by others, following the journalistic rule that “names make news.” Thus his reputation snowballs, and soon, probably against his will, he has become a colorful figure, credited with fabulous characteristics over and above the competence in war command for which he has been conditioning himself all his life.

His fame may not have gone to his head, but there is nevertheless danger in this. Should he get to identifying himself with the figure as publicized, he may subconsciously start thinking in terms of what his reputation calls for, rather than of how best to meet the actual problem confronting him. A man’s judgment is best when he can forget himself and any reputation he may have acquired, and can concentrate wholly on making the right decisions. Hence, if he seems to give interviewers and publicity men the brushoff, it is not through ungraciousness, but rather to keep his thinking impersonal and realistic.

(Source: Pp 240 How They Won the War in the Pacific Nimitz and His Admirals By Edwin P. Hoyt)

Had Brian Williams read this, from a humble, taciturn Admiral, who deserved and could have had all the good press he wanted, Williams might have taken pause. The demise of Brian Williams, despite the protestations of many of those in the press, will be a very positive event if the press relearns its proper place, and refocuses itself on its own form of heroism that only it can do if it has true moral courage.

It certainly is needed.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.