In his March 20 speech in Louisville, Kentucky, President Trump sounded many familiar and important themes, including the importance of jobs, manufacturing, trade, and the need to revive the coal industry. And yet he also added a new and larger “meta-theme,” namely, the urgency of building up our industrial strength for the sake of economic and national security. That meta-theme, we might observe, is the essence of the “American System” of Henry Clay.

Henry who? Let’s let Trump, speaking on the 20th, describe him: “Henry Clay was the legendary Kentucky politician who became the eighth Speaker of the House in 1811.” The President continued, “Clay was a fierce advocate for American manufacturing. He wanted it badly.”

Then Trump pivoted from manufacturing to another favorite subject, trade— specifically, fair trade. He quoted Clay speaking of trade, back in 1832: “To be fair, it should be fair, equal, and reciprocal.”

Trump added that Clay always warned against trade that was not, in fact, reciprocal. Nearly two centuries ago, the Kentuckian railed against fake free trade, which “would throw wide open our ports to foreign production without duties, while theirs remains closed to us.”

To these words, Virgil can only add: The more things change, the more they stay the same. Yes, then and now, America must be wary of playing the sucker’s game of opening up our markets to imports, while other countries close down their markets to our exports.

And yet as we know, in many cases, it’s already too late: We’ve been suckered in our trade dealings with Japan, Mexico, China, and many other countries. Indeed, in 2016, Trump was fully alert to that reality when other politicians weren’t, and that’s a big reason why he’s in the White House today.

Indeed, Trump had a strong message last year, and now, in 2017, he is strengthening it by making a connection to the taproot of American economic nationalism—the “American System.” In fact, the 45th President name-checked Clay no less than seven times, and used the phrase “American System” three times.

This is big. This is historic. Why? Because it indicates that the platform of “Trumpism”—which elitist critics have dismissed as populist pandering and rank demagoguery—is in fact, an agenda deeply informed by the best traditions of American history. It was the American System that built up this country, giving us widespread prosperity and also, crucially, the material muscle we needed to win the wars we had to fight. The factories envisioned by Clay were, truly, the “arsenals of democracy,” to cite the famous phrase of Franklin D. Roosevelt that Trump, too, has proudly used.

In fact, it’s fair to say that the American System was the dominant economic school of thought in the US until the 1970s. Then, over the next few decades, it was disastrously pulled down, and today, we see the consequences all around us.

And yet now, thanks to Trump, the American System is showing signs of a comeback. Admittedly, the administration must put meat on the bones of Clay’s memory, but at least it has made a start.

One might think, incidentally, that reporters would take at least a bit of notice.

Yet the MSM never fails to surprise—and disappoint. Journalists, slavering after every last piece of scandal and gossip, almost entirely ignored Trump’s citing of Clay and his System in that Kentucky speech. There was no mention of it in Politico, nor in The Washington Post, nor in The New York Times, nor on CNN. Not even the The Louisville Courier-Journal took note. In fact, about the only reporting on it that Virgil could find came from Breitbart News’ Charlie Spiering.

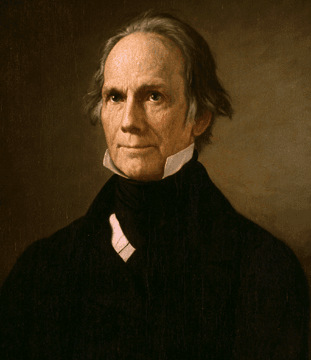

Okay, so let’s talk more about Clay (1777-1852). As Trump said, he was elected Speaker of the House in 1811, and yet in fact, his political career stretched over the first half of the 19th century. He was also a US Senator, Secretary of State, and a major party’s nominee for president in three national elections. (In one of those races, Clay was up against another Trump favorite, Andrew Jackson—but that’s a tale for another time.)

Henry Clay, 1777-1852 (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Yet it’s his American System that puts Clay permanently in the pantheon. And one fan of Clay’s, we might note, is another pantheon-dweller, Abraham Lincoln. Upon hearing the news of Clay’s death, Lincoln delivered a 5400-word eulogy for the leader that he described as “the beau ideal of a statesman.” And late in his life, the 16th President said of himself, “I have always been an old-line Henry Clay Whig” (the Whig Party being the predecessor to the Republican Party).

And so Virgil was intrigued when he heard Trump, in his earlier March 15 speech at Willow Run, Michigan, use the words “American Model” in the context of industrial renaissance. As this author observed two days later, Trump was hitting all the right Clay notes.

Okay, so what, exactly, is the “American System”? As the economic historian Michael Lind argued in his 2012 volume, Land of Promise: An Economic History of the United States, the three keys to a Clay-type American System are, first, a protective tariff against unfair trade practices; second, a pro-industry system of banking; and third, a steady stimulus for technological innovation.

We can look at each in turn.

First, fair trade. Clay’s argument, echoing that of his illustrious forerunner, Alexander Hamilton, was that American jobs and wealth depended on robust manufacturing capacity here at home, and if that required a protective tariff, so be it. We might note that another great American firmly in the Clay tradition was Theodore Roosevelt. Indeed, in 1895 TR declared:

Thank God I am not a free-trader. In this country, pernicious indulgence in the doctrine of free trade seems inevitably to produce a fatty degeneration of the moral fiber.

As we all know, the Trump administration has already scored successes in its bid to revive the Hamilton-Clay-Lincoln-Roosevelt line of thinking. The Trans Pacific Partnership is dead, as is the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership. Indeed, the Trumpians have forced other changes, too. Hence this encouraging March 19 CNN headline: “Trump 1, free trade 0: G20 drops pledge to fight protectionism.” Moreover, on March 20, Politico headlined, “White House prepares sweeping review of trade deals.”

Second, a pro-industry banking system. In a nutshell, America needs banks that focus on lending to industry, not speculating in high finance.

And so for the Trump administration, a key test will be its willingness to go toe to toe with Wall Street on the reimposition of Glass-Steagall-type banking regulation. That 1933 law, we can recall, simultaneously protected small depositors and restricted speculative, casino-style banking. Unwisely, Glass-Steagall was repealed in 1999, during the Clinton administration—and we all remember the speculation-driven financial meltdown of less than a decade later.

During the 2016 campaign, Trump called for a “21st century” version of Glass-Steagall. So now, in 2017, we will have to see what pro-industry reforms might emerge.

Third, stimulus for innovation. It is, after all, technological innovation, and the accompanying productivity increases, that generates wealth. Way back in 1776, Adam Smith pointed out this reality in his classic, The Wealth of Nations. In a revealing illustration, Smith cited improvements in pin manufacturing. As he noted, a single worker, working by himself, might be able to make one pin a day. And yet, he continued, if the work was done by a team in a factory, such that the production was specialized and divided—in the 18th-century anticipation of the modern assembly line—then ten workers might produce 48,000 pins in day. That’s a 480,000-percent increase in per-worker productivity. It’s from such quantum leaps in industrial output, of course, that our prosperity was built.

So now to the obvious question: How to get more such productivity increases? One answer, of course, is free enterprise. The study of history, as well as common-sense observation, tells us that competition in the marketplace has a way of bringing out the best performance in people. And thus it was, as Adam Smith so famously wrote, that an “invisible hand” increases aggregate well-being.

And yet we need more than that. We also need a systemic plan for improving technology. And here again, we can be guided by our own history.

We can start by thinking about Henry Ford, creator of the modern assembly line, whose company operated the B-24 plant at Willow Run.

Without a doubt, Ford was a genius who flourished in economic freedom. Yet the infant Ford Motor Company, founded in 1903, had a lot of help: Like every other American company back then, it was shielded by a tariff, and it had plenty of access to capital from local banks; those were the days before seemingly every bank was headquartered in New York City or Charlotte.

Yet there was another critical element in Ford’s success that’s needed just as much today: incentives for new technology.

And why is that? Because the free market does not always spur technological leaps, of the sort that Adam Smith noted in the late 18th century and that Ford engineered in the early 20th century. In fact, as often than not, the free market incentivizes cutting prices—and costs. And that’s because of the nature of competition. That is, one lemonade stand on the street, competing with all the other lemonade stands, tends to focuses on selling lemonade cheaper; there simply isn’t the time, or the money, to plan some outside-of-the-box boost in lemonade productivity. We can step back and observe: Cut-throat competition doesn’t necessarily build things—it cuts throats.

Is the reader perhaps wondering about this point about the way capitalism operates? Well, there’s no need to take Virgil’s word for it; we can get it from a capitalist. Here’s what the pro-Trump Silicon Valley investor Peter Thiel wrote in his 2014 book, Zero to One: Notes on Startups, or How to Build the Future:

Americans mythologize competition and credit it with saving us from socialist bread lines. Actually, capitalism and competition are opposites. Capitalism is premised on the accumulation of capital, but under perfect competition all profits get competed away.

In other words, if everyone’s competing, they’re not likely innovating. And that suggests that the font of innovation needs to come from somewhere other than the competitive entity itself, such as, for example, a university, a research institute, or some lone tinkerer.

Virgil can quickly note: This is not an argument against free-market capitalism. Instead, it’s an argument for the sort of rich economic “ecosystem” described by Michael E. Porter of the Harvard Business School, in hundreds of books and articles.

And to that point, it’s worth recalling that back in the 19th century, the government played a constructive role, starting with free public education—of the sort that young Henry Ford received.

Moreover, in those days, the federal government played a positive role, and not just on trade; most notably, Uncle Sam’s military spending was crucial to the industrial economy.

In the early 1800s, federal armories, then government-owned, began experimenting with the idea of interchangeable parts as a way of speeding up production. (Interestingly, this superior approach to making things was also known as the American System.)

Such Yankee ingenuity soon radiated through the entire economy, gaining momentum thanks to the huge industrial purchases of the Civil War—not just rifles and bullets, but also everything from railroad locomotives to the newfangled thing called the telegraph.

(As an aside, Virgil would say that the epic conflict between Blue and Grey can be seen as, in the final analysis, a fight in which Northern manufacturing buried Southern gallantry under an avalanche of steel. Thus we can conclude: In a battle between the daring cavalier and the well-equipped artilleryman, it’s best to bet on the fellow with the bigger cannonballs.)

In the wake of all this Civil War mass production, new factories, and new habits of thinking, were vastly encouraged. And so, by the beginning of the 20th century, Henry Ford could reap the benefits of this pro-business technological incentivization—and then, of course, thanks to his individual genius, greatly expand upon those benefits.

Still, if we think about the major technological leaps of the 20th century—including aviation, electronics, antibiotics, synthetic rubber, nuclear power, the Internet, and GPS—we see that the military, and war needs, were behind all of them. Yes, it was private enterprise that commercialized these gains, but it was not entrepreneurs that originated them. This phenomenon of war-led innovation caused the University of Minnesota historian Vernon W. Ruttan to ask, “Is War Necessary for Economic Growth?” His tentative answer was darn close to, Well, it sure seems that way.

Yet from Virgil’s perspective, we don’t need to start a war to enjoy economic growth; we just need to think about the next potential conflict, and diligently cultivate the economic strength we would require.

In fact, we need, as the philosopher William James argued more than a century ago, “The Moral Equivalent of War.” That is, if we think about what Ford Motor Company, working with the federal government—and 42,000 Michigan workers, including Rosie the Riveter—accomplished at Willow Run during World War Two, we can draw all the economic inspiration we need to be rich—without dropping a single bomb.

With those winning precedents in mind, we can close by outlining an economic opportunity—and a political necessity. Namely: the full use of our abundant reserves of coal.

Once again, we can return to Trump’s speech in Louisville. As everyone knows, coal is a major industry in Kentucky—or at least it was. So it must have been heartening to Kentuckians to hear Trump say:

We are going to put our coal miners back to work. They have not been treated well, but they’re going to be treated well now. Clean coal, right? Clean coal.

Yes, just as Trump said, coal must be clean. And in its natural state, it’s true that coal contains toxic elements—including cadmium, chromium, and mercury—that are released into the atmosphere upon burning. Fortunately, thanks to technology, it’s possible to “scrub” coal. And if coal needs still more scrubbing to even cleaner? Very well, it needs more scrubbing; that’s a further mission for patriotic science, serving the public interest.

However, as we know, the environmentalists choose to say that none of this is possible, that coal is irredeemably dirty. And so, the greens continue, we must stop mining coal altogether—their favored phrase is “leave it in the ground.” Indeed, green activists, financed by billionaires such as Michael Bloomberg, have been litigating and regulating to shut the coal industry down, leaving thousands of workers, and their communities and states, stranded.

And sadly, they’ve been effective. We might consider this March 21 headline in Axios, a buzzy new Beltway publication: “The coal industry is sick—and it’s terminal.” As the accompanying chart shows, coal production nationwide has fallen by about a third in the last decade, and coal-mine employment has fallen by two-thirds in the last three decades.

Surveying the dire situation, we might make three points:

First, the Beltway seems weirdly eager to see the coal industry, and its workers, wiped out. Virgil wonders if it has something to do with anti-Red State prejudice. He even wonders if it’s a kind of slow-motion economic hate crime.

Second, a shutdown of coal would be a huge economic loss to the US. After all, according to Department of Energy, the total amount of coal underground in the US is 3.9 trillion tons. At the current price of around $50 a ton, that’s about $200 trillion dollars. Bloomberg and his hirelings might not need any of that money, but millions of Americans do, and so does the nation as a whole.

Third, we must be mindful of political reality—that is, the power relationships involved in mining and burning coal, as well as other fossil fuels. Virgil admits that he himself is not worried about global warming, but nevertheless, he believes that we all would do better if we acknowledge the likelihood that some sort of compromise between Big Green and Big Coal—make that, now, Little Coal—will be needed if miners are to keep their jobs, let alone have new jobs.

As Trump said in Louisville, we can have clean coal if we want it, and so let’s get it. Fortunately, the American System was designed to foster exactly that sort of technical evolution. Indeed, as we think about cleaning up coal, we must also think about dealing with carbon dioxide, aka, greenhouse gas. And so Virgil admired a recent article making the case for a crash national program of carbon capture.

Yes, Virgil was thrilled to see Trump talking about the American System of conscious economic development. It was a good idea then, and it’s a good idea now. So let’s put this new/old system through its paces!

And there’s no better American project than reviving the coal industry, and putting our miners back to work.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.