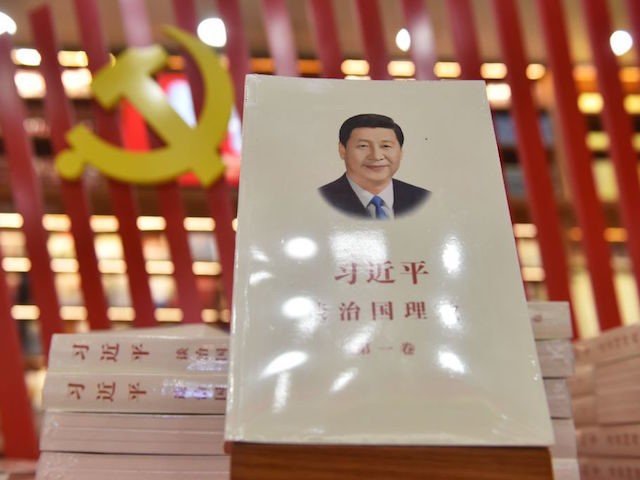

At the tail end of 2017, Chinese Communist Party leader Xi Jinping delivered a 3.5-hour speech appointing himself the head of a “new era” of Chinese global hegemony, the indisputable leader of world communism.

Jiang Zemin yawned. And checked his watch. And read the newspaper. It was a long speech.

Jiang, once held the position Xi was then abusing to harangue his peers. He was notably at the helm of the country during the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre, “correcting” reporters who referred to the killings as a “tragedy” and insisting that the killings were necessary, as “what actually happened was a counterrevolutionary rebellion aimed at opposing the leadership of the Communist Party and overthrowing the socialist system.” Jiang Zemin is part of the Communist Party old guard, a ruthless killer considered the hardest of the Party’s hard line.

Yet as Xi proclaimed China would now “take center stage in the world” at America’s expense, Jiang, 91 at the time, could not stop yawning. His disinterest in China’s dictator du jour became an internet meme, stealing headlines from the most important speech of Xi Jinping’s career.

Most dismissed it as the intransigent behavior of a nonagenarian with nothing to lose, but it would prove to foreshadow an unexpected turn in Xi’s legacy: the chairman, already dealing with widespread revolts from human rights activists, lawyers, Christians, Muslims, Tibetans, and anyone else inconvenient to his ambitions, would spend much of 2018 violently cracking down on fellow communists.

Labor rights activists and Maoist student groups who had previously expressed reservations about Xi’s move to enshrine his name into the nation’s constitution, joining Mao Zedong and Deng Xiaoping grew more vocal as the months passed in 2018, protesting to Xi’s tight-fisted control of labor unions, permissive attitude towards the violation of workers’ rights, and coziness with multinational corporations and the Davos set. By the end of the year, police were beating up and “disappearing” Maoist college students for attempting to celebrate the communist icon’s birthday.

There is no indication that China’s most stalwart Marxists have reconsidered their ideal political system, or that they will pose a threat to the Communist Party whenever Xi’s tenure ends, but their rejection of Xi weakens a leader who has spent most of his political capital attempting to impose his will on the outside world – colonizing by land and sea – and neglected his domestic duties.

The first half of 2018 featured much of the repression typical to Xi’s regime: the shutdown of human rights law firms, suspicious disappearances of those publicly critical of Xi, even the establishment of internment camps for Muslim Uighurs, which Xi has long considered enemies of the state. By August, however, new foes had appeared on the scene: Maoist organizations, which hoped to assemble to urge Xi to stop embracing what they considered capitalism.

Agitating Maoist websites and publications were the first to go. According to Radio Free Asia (RFA), Chinese police spent much of August raiding the headquarters of a variety of Maoist websites, arresting their editors and accusing them of counterrevolutionary activity. In the last week of August, “more than 20 people, mostly from Guangdong, came to our offices … armed with a search warrant and a notice of criminal detention made out for [fellow editor] Shang Kai,” the editor-in-chief of “Red Reference,” Chen Hongtao, told RFA. “They searched every corner of our offices, and even smashed a cupboard, and took our computers, our books away in a bunch of boxes.”

That same week, police “disappeared” seven of the editors producing the “Epoch Pioneer,” another Maoist publication.

Elsewhere, in front of the Jasic Technology factory in Shenzhen, dozens of Maoist activists clashed with police after attempting to peacefully protest what they believed were violations of laborers’ rights at the factory. Those arrested, believed to total at around 50, included both workers at the factory and students from a nearby university who stood in solidarity with the workers.

The Chinese regime never bothered to explain the shutdown of the Maoist websites, but the outcry and confusion following the Jasic factory incident did prompt an explanation from the Global Times, a state media outlet.

“Police recently issued a preliminary report on a series of worker-related incidents at the Jasic Technology Co Ltd,” the newspaper reported. “Police investigators say that an unregistered, foreign-funded illegal organization named ‘dagongzhe zhongxin’ (center for migrant workers) incited the workers and hyped the incident on the internet.”

The Global Times insisted in its report that “a trade union without government involvement is not in accordance with Chinese characteristics,” citing an unnamed “expert,” who questioned the legitimacy of the arrested’s Marxist beliefs.

Three months later, police once again targeted the protesters, now organized into an association called the Jasic Workers Support Group (JWSG). Over a dozen activists, most young students, “disappeared” in November throughout some of China’s biggest cities. Their social media accounts ceased to exist after their disappearance. At Peking University, where the most violent arrests occurred, police said what had occurred was merely the “police department lawfully taking into custody a criminal suspect,” without elaborating. The Marxist students left behind, outraged, asked, “What have we been doing in the Marxism Research Club? We only read Marxist works. What is wrong about that?”

Chinese authorities were not able to blame foreign actors for the next crackdown on communists.

On Mao’s birthday, December 26, Chinese ununiformed police “disappeared” the head of the Marxist Society of Peking University. Qiu Zhanxuan was reportedly whisked into a car and driven away under suspicions of wanting to organize events celebrating Mao, perhaps due to concerns that the events would eclipse those for Xi. Qiu resurfaced a day later, but by then the government had begun replacing the leadership of the student Marxist society with known allies of Xi Jinping.

University professors announced that the group would be “restructured” with no room for Qiu or any of the leaders of the groups.

The students fought back, triggering a brawl with police and yet more arrests.

“This was, plain and simple, a plan to restrict my personal freedom and to use these inhuman and illegal means to stop me from going to commemorate Chairman Mao,” Qiu said following the incident.

Xi not only lost the support of radical leftist students and low-level workers in 2018, but some of the most highly respected members of Chinese communist society: the veterans of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA). In October, PLA veterans staged a protest so large in the city of Pingdu, northern China, that police were ordered to block the city off. The protests demanded the rightful pensions of the workers in question and an end to police beatings, which had become increasingly common as the veterans grew impatient and desperate to receive their salaries.

Entering 2018, Xi appeared to have successfully stifled opposition from the usual anti-communist sectors. In Jiang Zemin’s day, the solution to such a problem was easy: death and torture to the few who dared revolt. On the eve of 2019, however, it is difficult to find any sector of Chinese society that vocally supports Xi, leaving dangerously unanswered who would remain alive if Xi used the same tactics to subdue all those opposed to him.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.