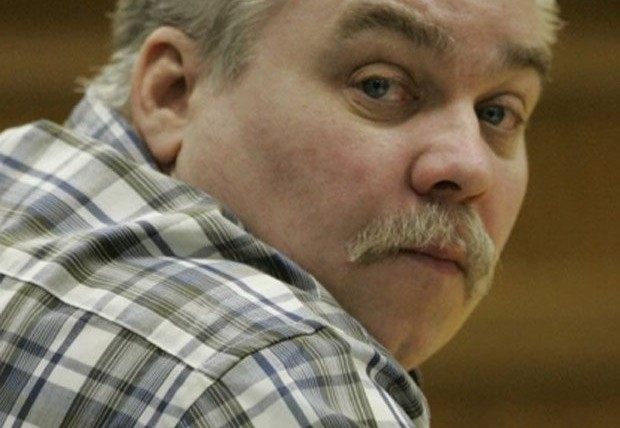

Like many over the holidays, I was enthralled by the Netflix 10-part true crime documentary series “Making a Murderer.” Over just two days, I gobbled the whole thing up and repeatedly tweeted out praise for what is objectively a remarkable achievement. Over the course of 10 years, documentarians Laura Ricciardi and Moira Demos whittled down hundreds of hours of footage into a fraction of that to present the case of Steven Avery, a working class Wisconsin man convicted of a brutal murder just two years after serving 18 years for a rape he didn’t commit.

Also convicted was Brendan Dassey, Avery’s learning-disabled 16 year-old nephew, who repeatedly confessed and recanted his role in aiding his uncle in the brutal rape, torture, murder, and mutilation (the corpse was burned in a fire pit) of the victim, 25 year-old Autotrader photographer Teresa Halbach. Both received life sentences without any chance of parole.

What surprised me is that afterwards I appeared to be the only person who was still sure Avery and Dassey were guilty. That doesn’t mean that the Manitowoc Country justice system covered itself in all kinds of glory. It did not. There are a number of legitimate questions that add up to an over-zealous prosecution and investigation, up to and including the planting of evidence. This is known as “framing a guilty man,” and regardless of one’s intent, it is not okay.

Nevertheless, the forensic and circumstantial case presented against Avery left no room in my mind for reasonable doubt of his guilt. Avery was the last person to see Teresa Halbach alive. Her charred remains were found in his fire pit. His hand was freshly cut, and his blood found in her vehicle. Her vehicle was found hidden on his property. Avery and Dassey both admitted to using the burn pit the afternoon and evening of her murder.

Who else could have possibly murdered this young woman?

The turning point for me came with the blood evidence. Avery’s extremely able defense attorneys (paid for by the suit Avery filed against the state for his wrongful conviction) suggested the blood had been planted by police. Police had in their possession a vial of Avery’s blood. However, a preservative is added to blood samples and after conducting a test, no less than the F.B.I. concluded there was no preservative in the blood taken from the vehicle.

Unless you want to believe the same F.B.I. that loves to embarrass locals was in on the conspiracy, that is forensic evidence no defense attorney can talk around.

On the issue of the nephew, if you believe Avery is guilty, you have to believe Dassey is guilty and that they burned the body together. I’m also not as horrified as others over the way in which the police got Dassey to confess. Sure, they pushed him but he was never threatened. The investigating officers never even raised their voices (that I recall). And even if you have a 70 IQ, you don’t confess to something you didn’t do, much less rape and murder.

At the risk of digressing too much, let me further explain my belief in Avery and Dassey’s guilt:

When it comes to America’s criminal justice system, I am a small “l” liberal, a true believer in an adversarial process that places all of the burden on the State; a true believer in the rights of the accused and an advocate for the checks and balances of our appeals process, especially when it comes to the death penalty. When you give the State the power to strip an individual of his freedom or life, that power must be continually tested, prodded, and challenged.

At the same time, I am not a cynic. This is primarily because of my faith in American juries. I am a firm believer in the common sense and decency of the everyday American, the people plucked from their lives and handed the awesome responsibility of being the ultimate deciders in a criminal case. Who better? People who work within the system can be easily corrupted. A “professional jury” could easily be corrupted. Our jury process is how we avoid Star Chambers. As it stands now, the only responsibility and obligation a juror has is making a decision he or she can live with.

In short, while I naively believed the “Making a Murderer” filmmakers had told the full truth, in the end I sided with the evidence and those 12 everyday people who came together in unison to convict. It is also no small thing that Avery could afford top-notch attorneys. This was the opposite of a “poor man” against the criminal justice system.

But back to our story…

As most of you know, “Making a Murderer” quickly became something of a phenomenon, and as a result, a thousand editorials were launched proclaiming the innocence of the accused and a demand for a retrial. Except for a few tweets, I remained silent through all of this. While I disagree on the point of the duo’s guilt, I did agree that they deserve a retrial.

Now, however, and to my great disappointment, the worm has turned with the revelation of the full case against Avery and Dassey. There is just no question that this documentary is pure propaganda — both misleading and corrupted. What Ricciardi and Demos chose not to tell the viewers is moral malpractice, and now that the full truth is coming out, a well-deserved backlash is in full force.

This is what the documentarians did not want us to know:

- The bullet found in Avery’s garage came from Avery’s .22 rifle and contained Halbach’s DNA.

- Handcuffs and leg irons were found in Avery’s home (a trailer), and Steven Avery admitted to purchasing them (for his girlfriend).

- The mysterious key to Halbach’s car, the key that seemed to appear out of nowhere, has DNA from Avery’s sweat on it. You can plant blood, hair, and fibers. You cannot plant sweat.

- Avery’s sweat DNA was also found on Halbach’s vehicle.

- Using a false name, Avery specifically requested Halbach take the photographs of the vehicle he wanted to sell.

- On three different occasions, on the day she was murdered, Avery not only called Halbach, he twice attempted to hide his identity using a *67 feature.

- Brendan Dassey’s mother reported that, per her son, the large bleach stains she saw on his jeans on the night of the murder came from helping his uncle clean the garage floor, where the .22 bullet was found. The documentary makes a very big deal out of the lack of forensic evidence at the murder scene (the garage) but tells us nothing about the bleach stains.

- Halbach’s cell phone was found in the burn pit. Slate explains why it matters that this crucial piece of evidence was left out by the filmmakers:

The issue of the cellphone is especially problematic. The series implies that whoever accessed Teresa Halbach’s phone on the day she died (which both Halbach’s brother and her ex-boyfriend admit to doing) might have been involved in her murder. But anyone with physical access to Halbach’s phone would have also been able to access her voice mail. Is that why this piece of evidence was left out?

- Per a cellmate, while in prison, Avery openly fantasized about building a torture chamber for women.

- Avery has a very troubling history of sexual violence. Slate again:

What’s more, at the time of Halbach’s disappearance, Steven Avery was being investigated for the alleged 2004 sexual assault of a teenage female relative, who claimed that Avery threatened to “kill her family” if she told anyone about it. Worse, Dassey alleged in a phone call to his mother that in the past Avery had touched him in places that made him “uncomfortable.” Stachowski claims that Avery beat her repeatedly, and Penny Beerntsen, who mistakenly identified Avery as her attacker in the 1985 rape, says that Avery called her up shortly after his exoneration, asking for money to “buy a house.”

- Teresa Halbach had been out to Avery’s place in the past to take photographs and didn’t want to go back that day because he had once answered the door wearing only a towel.

Crucial Reading: David Harsanyi’s “Steven Avery is Guilty as Hell” and The New Yorker’s “How ‘Making a Murderer’ Went Wrong.”

When you are producing a 10-part docu-series, “time constraint” is not a valid excuse for leaving out all of this vitally important and relevant information. Moreover, Ricciardi and Demos cannot even argue that they left out Avery’s alleged assault against his own relative for fear the sensationalist nature of the charges would prejudice viewers against Avery. The filmmakers had no problem reporting sexual harassment charges leveled at Avery’s prosecutor, which were irrelevant to Avery’s prosecution.

Because I have always found fact much more intriguing and compelling than fiction, for decades I’ve been a true crime addict. As long as the presentation isn’t meant to titillate or exploit, whether it is documentaries, books, or a brilliant television series like “Forensic Files,” these dual examinations of the human condition and the American judicial system endlessly fascinate, especially when they serve as an invaluable court of last resort.

“Making of a Murderer” does not belong in this genre.

As well-made and addicting as “Making a Murderer” is, it is itself a moral crime, a piece of manipulative propaganda.

And we the viewers are merely collateral damage in this unforgivable injustice perpetrated directly against the family of Teresa Halbach.

Follow John Nolte on Twitter @NolteNC

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.