In Part One of this series, we saw how, back in 1941, President Franklin D. Roosevelt chose to look past the serious flaws in the Russian regime of Josef Stalin in order to isolate, and confront, the mortal threat from the German regime of Adolf Hitler.

And we compared the choices FDR made—and Winston Churchill, too—to the situation confronting another New York-born President, Donald Trump, as he now considers working with Russia to deal more effectively with China.

So in this Part Two, it’s worth taking a closer look at American thinking back then—as seen in the Congressional debates of 1941—as America sided with Russia in a world struggle. At the time, Hitler was the cruel master of Western and Central Europe, and Stalin was the cruel master to the east. So to many observers, the two men, and their regimes, were little different. Yet to FDR, and to Churchill, it was obvious: Hitler was the real menace. As we shall see, the opponents of FDR’s Russia policy often made valid points; yet still, the greater wisdom was with the proponents.

On December 29, 1940, in his “arsenal of democracy” speech, Roosevelt made the case for sending weapons to anti-Nazi fighters, notably, the British: “The people of Europe who are defending themselves do not ask us to do their fighting. They ask us for the implements of war, the planes, the tanks, the guns, the freighters which will enable them to fight for their liberty and for our security.”

Inhabitants of the former Soviet-occupied Polish city of Lwow wave at a passing truckload of German soldiers as Nazi troops take over the city on July 2, 1941, according to the caption passed through German government censors. The city is now known as Lviv in Ukraine. (AP Photo)

The Great Debates of 1941

In January of the new year, FDR formally requested that the 77th Congress enact a Lend-Lease program, so that American aid could flow.

The Congressional debate was stormy; perhaps the most virulent opponent of Lend Lease was a four-term Democratic Senator from Montana, Burton K. Wheeler. As he said on the Senate floor, “Never before has a Congress coldly and flatly been asked to abdicate.” Addressing his fellow Democrat, the man in the White House, Wheeler continued, “If the American people want a dictatorship—if they want a totalitarian form of government and if they want war—this bill should be steamrollered through Congress, as is the wont of President Roosevelt. Approval of this legislation means war, open and complete warfare.” And such a war, Wheeler added starkly, “would plow under every fourth American boy.”

Yet at the same time, most Americans felt admiration for Churchill, and there was, of course, a deep reservoir of support for Britain—to say nothing of growing revulsion toward the Nazis, who were ever more brutal in their occupation of Europe. So in March 1941, Congress passed Lend-Lease.

Then, just three months later, history took another surprising, and epic, turn. On June 22, 1941, Hitler broke yet another agreement, attacking, this time, the Soviet Union. Operation Barbarossa was the greatest invasion in history; some 3.8 million Axis soldiers, spearheaded by thousands of airplanes and tanks, blitzed their way across the Russian frontier. In other words, less than two years after it was made, the evil alliance between the bad guys was undone—much to the relief of the good guys.

Operation Barbarossa, Two Wehrmacht soldiers are holding a Swastika flag to protect against friendly fire. 1942. Fighting is going on nearby on the Eastern Front in Russia, Soviet Union. (Photo by Galerie Bilderwelt/Getty Images)

As Sir John Colville, Churchill’s private secretary, recorded, the Prime Minister’s instant response, on hearing the news, was a “smile of satisfaction.” In a radio address to the British people that evening, Churchill laid out the changing war situation: First, he recalled, with gratitude, the generosity of the U.S. Lend-Lease program; second, he reiterated his view of Hitler: “a monster of wickedness, insatiable in his lust for blood and plunder”; and third, he welcomed the Russians into the anti-Hitler camp, albeit with caveats. As he said, “No one has been a more consistent opponent of Communism for the last twenty-five years. I will unsay no word I have spoken about it. But all this fades away before the spectacle which is now unfolding.”

Churchill’s point was that it was now time to look forward: “The Russian danger is therefore our danger, and the danger of the United States, just as the cause of any Russian fighting for hearth and house is the cause of free men and free peoples in every quarter of the globe.” Churchill, as well as Roosevelt, albeit more quietly, could see that they’d been given a gift—the gift of an ally against Hitler.

As a gesture of good faith, the British immediately launched a modest aid program to the Soviets; that is, they sent cargo ships into the U-boat-infested waters of the North Sea, heading toward the Arctic Circle and thence to the Russian port of Murmansk.

Yet everyone knew that if major aid was to be delivered to the Soviets, it would have to come from the United States. Thus in November 1941 began another debate in Congress over Lend Lease—whether or not to extend it to the newly beleaguered Russians. (Actually, in point of fact, FDR had already started delivering aid to Moscow; the specific question on the floor was whether to revise the Neutrality Act to allow more effective U.S. shipping of such aid.)

Some Members of Congress were flatly opposed. One such was Rep. Martin L. Sweeney (D-OH); as he said of Hitler and Stalin, they were “two diabolical dictators”—and he didn’t want Uncle Sam to have anything go do with either of them. (The preceding quote, and all succeeding quotes from lawmakers, can be found in the 1941 Congressional Record.)

Some lawmakers even argued that the Soviets were worse than the Nazis. In the words of Rep. Clare Hoffman (R-MI), “Let the President clean his own house; quit issuing half-truths . . . Let him quit telling us such fairy tales as the one that there is freedom of worship, religious freedom, in communistic Russia where the Government creed is the denial of the existence of a Deity.” And Rep. E. Harold Cluett (R-NY) recalled that the Russians had never repaid their war debts from World War One, further recalling also the Soviet attacks on Finland, Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. Rep. Gordon Canfield, (R-NJ) was more personal; he told his colleagues the story of a Polish-American doctor from his district, who had gone to help his mother country in 1939, only to disappear within Soviet-occupied Poland.

Rep. Compton I. White (D-ID) worried that the debate over aid to Russia was in and of itself harmful; he sighed that it was “sowing the seeds of strife and dissension.”

Others were more direct in their warning, saying that aid to Russia was a prelude to war. As Rep. William T. Pheiffer, (R-NY) declared, “The argument that permitting our merchant ships, flying the American flag, laden with war materials for England and Russia, convoyed by American warships, to sail into the ports of England and Russia will not involve us in total war is so tenuous as to be almost absurd. It would not be given credence by a boy in the kindergarten of a school for the feeble-minded.”

Sen. Robert Taft (R-OH) was less politically incorrect and more succinct: “In my opinion, the passage of the joint resolution would mean war.” And another Republican Senator, Hiram Johnson of California, dilated on that theme: “Senators, it is war, war . . . that none of us as Americans can afford.” He added, “I care not for Germany and Hitler’s crimes. I care not for Russia and Russia’s greed. I care not for any of those countries. . . Do not declare war. Do not plunge this country into that sort of holocaust.”

Thus those against helping Russia made a strong case. And yet those in favor made the stronger case; the crux of their argument was that it was best to get as many other countries as possible fighting against Hitler.

One such was Rep. Charles Eaton (R-NJ), who declared, “I believe with all my heart that it is better for us to have Mr. Stalin standing up to the Germans now than it would be, later on, even on our own soil or elsewhere, for us to stand up to him alone.” Rep. Pete Jarman (D-AL), added, “Russia, whether we admire her form of government or Stalin or not, is fighting the fight we want to see won.”

Sen. Ellison D. Smith (D-SC) echoed Churchill’s quip about Hitler and hell, chortling, “I would ride the devil as long as he was going toward heaven, but when he turned off I would get down. I would use Mr. Stalin to help annihilate Mr. Hitler.”

FDR’s legislation passed, and American aid to the Russians accelerated. Indeed, on December 5, 1941, as the Nazis came within a dozen miles of Moscow, the Russians counter-attacked, grinding the German offensive to a halt. It was a partial victory, for sure, as the Germans were still deep inside Russia. And yet even so, it was a victory; Roosevelt’s help-the-Russians strategy had been vindicated.

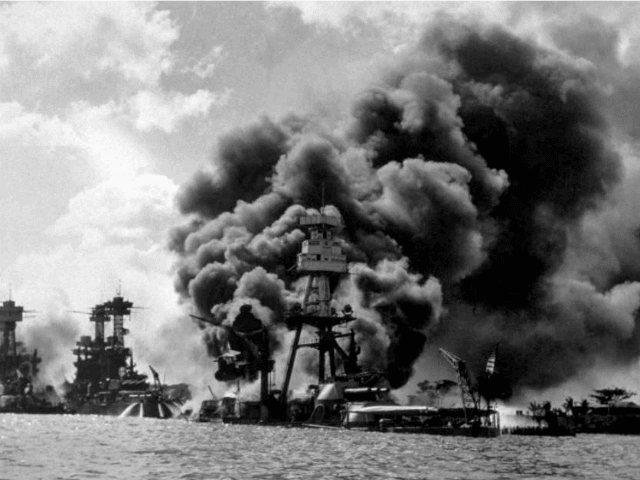

Then, just two days later, on December 7, 1941—the date that will live in infamy–the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor.

Now everything had changed. American isolationist sentiment evaporated, and support for the U.S.S.R. in its fight against Germany was seen as desirable; after all, every other anti-Nazi combatant in the war was, in effect, saving American lives. During World War Two, adjusting for today’s dollars, Lend Lease delivered $43 billion to the Russians.

For their part, at least in their candid moments, the Russkies acknowledged the benefits they had received. As Stalin himself said during the fighting, “The United States is a country of machines. Without the use of these machines through Lend-Lease, we would lose this war.” And in 1963, Gen. Georgy Zhukov, the top Soviet commander, remembered Lend-Lease well: “You cannot deny that Americans drove many materials, without which we would not be able to form our reserves and could not continue the war.”

Yet still, the U.S. received the even greater benefit. In World War Two, it’s been estimated that up to 80 percent of German casualties were inflicted by the Red Army.

The Lessons of 1941 for 2018

As we have seen, because of his desire to help the Russians, Roosevelt was called just about every name imaginable: dictator, warmonger, holocaust-bringer. To be sure, thoughtful criticisms were raised, too, and that’s why small “d” democratic debate is so valuable—at its best, argumentation is a learning process. And yet in the end, the 32nd President’s argument was stronger, and his strategy was vindicated.

So now today, what is to be made of the 45th President? We know that Trump, too, is being labeled in the most savage possible terms—dupe, traitor, and on and on. And yet as we saw in Part One, Trump’s ability to work with Putin is already paying dividends, in terms of the recent agreement on Syria that puts the squeeze on Iran.

So what will come next? The short answer, of course, is that the future is unknowable. As the events of 1941 remind us, the next Barbarossa, or Pearl Harbor, will hit us by surprise, thus upending even the most carefully crafted plans.

In the meantime, the only thing we can be sure about is that it helps to have strong allies, or at least strong contacts, because strength matters when the going gets rough—and the last thing we want is for strong players to be on the side of our opponents. That is, were Russia to ever make an alliance with China, well, that would be truly ominous.

Perhaps Virgil should give the last word to another old-timer, Henry Kissinger. In a recent interview with The Financial Times, the former Secretary of State was asked if Trump might already be performing “the unacknowledged service of calming the Russian bear.”

Kissinger answered: “I think Trump may be one of those figures in history who appears from time to time to mark the end of an era and to force it to give up its old pretenses.”

Kissinger was hardly unstinting in his praise for Trump, and yet still, the wily old man, born in 1923, is old enough to remember the watershed year of 1941—and he himself served in the U.S. Army in World War Two. So Kissinger, both a survivor and a scholar, knows full well that having the Russians on our side back then made a huge, and life-saving, difference.

So is the situation of 2018 anything like that of 1941? That’s the essence of Trump’s big bet. Recalling the great alliance of World War Two, Trump told Fox News’ Tucker Carlson last week, “Russia . . . helped us win the war . . . Russia really helped us . . . I’m not pro-Russia . . . I just want to have this country be safe.”

If Trump, as well as others on his side—including former Breitbart chief Stephen K. Bannon—are correct about China, then it’s obvious: This country will need the cooperation of Russia to be safe.

This is the secon of three parts. Next: The President and China

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.