This story originally appeared at Vox.

Before this year, Ebola was a disease relegated to remote villages in Africa. Even public health officials didn’t worry about it spreading very far. Until recently, they would probably tell you that the virus typically burned out after ravaging only a handful of people.

But then came 2014.

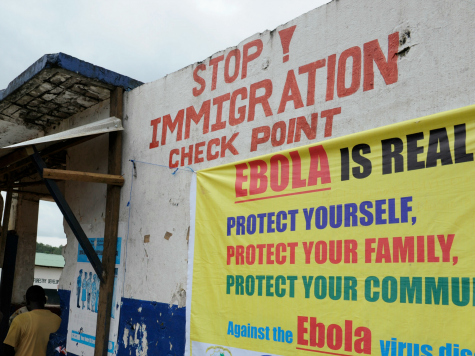

This year has, in many ways, rewritten the Ebola rulebook. We’re in the middle of an unprecedented, nightmarish epidemic that has spread from a rural rainforest region in West Africa to large urban centers. The World Health Organization’s director has called it “the greatest peacetime challenge” the world has ever faced, with the number of cases doubling each week.

Now, health care officials are starting to talk about a worst-case scenario for Ebola. The World Health Organization projects that 20,000 people will be infected in November. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, meanwhile, projects 1.4 million people could be infected by January, assuming that Ebola cases continue to increase exponentially and are underreported by a factor of 2.5.

1) The best methods we have to contain Ebola are failing

Public health officials are terrified that one of the cornerstones of an Ebola response — tracing the contacts of those infected — can’t keep pace with the epidemic.

In the past, trusty volunteers and public-health workers would follow all the people who had come into contact with an Ebola patient for 21 days (the virus’ incubation period) to make sure that those people didn’t develop any of the early flu-like symptoms of the disease. If anyone did, they would be put in quarantine to be monitored further and to ensure they didn’t give the virus to anyone else.

This method worked extremely well. It helped to curb every previous known Ebola outbreak in history — and it even seems to have worked in the small outbreaks this year in Senegal and Nigeria, which have just reported zero suspected cases.

But in Liberia, Sierra Leone, and Guinea, which each have thousands of infected people, contact tracing becomes impossible. Consider this: the WHO estimates that every person in this region has at least ten contacts. Liberia already has over 3,000 cases of Ebola. That would be 30,000 potential contacts to follow-up. Imagine, if by the year’s end, we see nearly 300,000 cases.

So the best method to curtail this untreatable disease is useless at the scale of the outbreak before us. And this keeps health professionals familiar with the disease up at night.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.