Ottawa (AFP) – More than 600,000 Metis and non-status Indians are “aboriginal” under Canadian law, the Supreme Court said Thursday in a landmark decision hailed as righting a historical wrong.

The Metis are descendants of French fur traders and North American Indian women who settled in western Canadian provinces in the early days of European colonization, including a large community in Manitoba province’s Red River Valley.

Long referred to as “half-breeds” by the British Crown and later by the Canadian government, their status as indigenous people had never been fully recognized.

There’s a total of 1.4 million indigenous people in Canada, representing 4.3 percent of the population, based on a 2011 survey by the government statistical agency.

The court ruling — which ends a 17-year legal saga started by former Metis leader Harry Daniels, who died in 2004 before the case went to trial — means the Metis can now collectively negotiate treaties and rights with the government, including access to federal health, education, language and cultural programs.

It also paves the way for Metis land claims and self-governance.

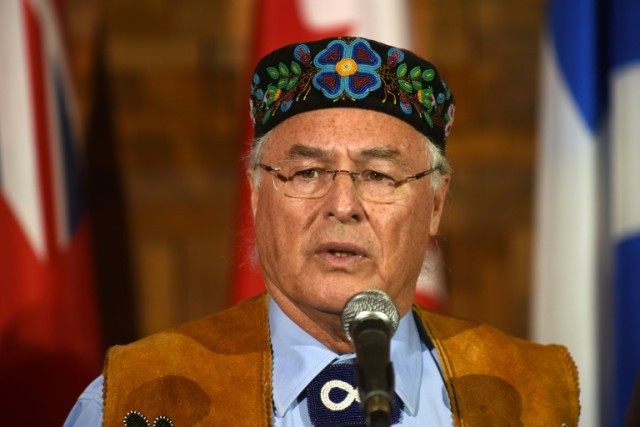

“When you’re ‘non,’” said chief Dwight Dorey of the Congress of Aboriginal Peoples, referring to non-status Indians or natives living off reservations, “you don’t exist.”

“That term should be gone forever from the English language in Canada. We are all status now,” he said.

“We’ve been fighting for so long to get justice for our people in this country,” added Gerald Morin of the Metis Nation of Saskatchewan, speaking outside the courthouse.

“Today our people are a landless people living in poverty in the margins of society… And now, for the first time in our history, we’re hopeful.”

– ‘Righting a wrong’ –

Metis suffered discrimination under the colonial system just like their “Indian” peers and at times were lumped in with them if it was convenient or expedient for Ottawa, for example, in negotiations to ensure that natives did not block the construction of a pan-Canadian railway in the late 1800s.

Consecutive federal and provincial governments steadfastly refused to officially acknowledge jurisdiction over the Metis, leaving “no one to hold accountable for (their) inadequate status quo,” the court said.

“The historical, philosophical and linguistic contexts establish that ‘Indians’ includes all aboriginal peoples, including non-status Indians and Metis,” the Supreme Court justices concluded in their unanimous decision.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has made reconciliation with Canada’s indigenous peoples a key policy of his administration.

“We’ll be engaging with indigenous leadership to figure out the path forward, but I can guarantee you one thing: the path forward will be together,” he said in reaction to the decision.

Jacqueline Romanow, a professor at the University of Winnipeg who is coincidentally also Metis, told AFP the decision “is part of Canada coming to terms with its indigenous identity and giving recognition and respect to First Peoples of this country.”

“For the longest time, Metis struggled to fit in in both Indian or mainstream societies, so this is recognition of some of the wrongs against the Metis people, and a step toward addressing those wrongs,” she said.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.