A story in the Washington Times last week brought the issue of reparations front and center into Louisiana’s upcoming gubernatorial election, in which the state’s incumbent Democrat Gov. John Bel Edwards is seeking a second term in office.

Edwards faces two Republican opponents, Rep. Ralph Abraham (R-LA) and businessman Eddie Rispone, in the October 12 “jungle primary.” Should no candidate secure 50 percent of the vote, the top two finishers will face off in a runoff election in November.

Many prominent Democrats are on record calling for the payment of financial reparations, either directly by the descendants of slave holders, or indirectly by the federal government or state governments, to the descendants of those slaves for the economic and legal harm done to them.

At a forum for the three top gubernatorial candidates held at the Baton Rouge Press Club on September 23, Edwards said that reparations is “not something I have studied or am considering,” a surprising comment, given his party affiliation and his family’s history of slave owning.

“I am focused, however, on making sure that we have increased access to opportunity and prosperity,” Edwards added.

While Edwards refused to make a comment either for or against reparations, Abraham addressed the issue head on.

“I’ll answer this question that the other two gentlemen have not. I am against reparations,” Abraham said at the event.

Gov. Edwards’ unwillingness to address the issue of reparations stands in stark contrast to his previous statements and political advertisements that tout his family’s strong Louisiana heritage, one which is deeply tied to slavery.

“In the case of Mr. Edwards, slave labor appears to have been instrumental in the family’s rise to affluence. Records show that spacious family homes, such as Edwards Manor near Wilmer, were built by slaves who used timber they cut and hued from the family’s extensive land holdings,” the Washington Times reported:

Conveyance records in the St. Tammany Parish Courthouse show Daniel Edwards, a friend of Andrew Jackson’s and the family patriarch who first held elected office in Louisiana, buying and selling slaves.

The governor’s great-great-grandfather, Nicholas Stone Edwards, then became a member of the exclusive “planter” class, which historians generally describe as people who owned more than 20 slaves.

Census records show Nicholas Stone Edwards expanded the family’s slave ownership. In 1830, he owned 35 slaves. By 1860, on the eve of the Civil War — in which he fought on the Confederate side leading what was known as the “Edwards Guards” — the family’s slave holdings had swelled to 57 people.

Breitbart News has confirmed the basics of the Edwards family history outlined in the Times article, though it appears the slave holdings of Gov. Edwards’ ancestors were more extensive than initially reported.

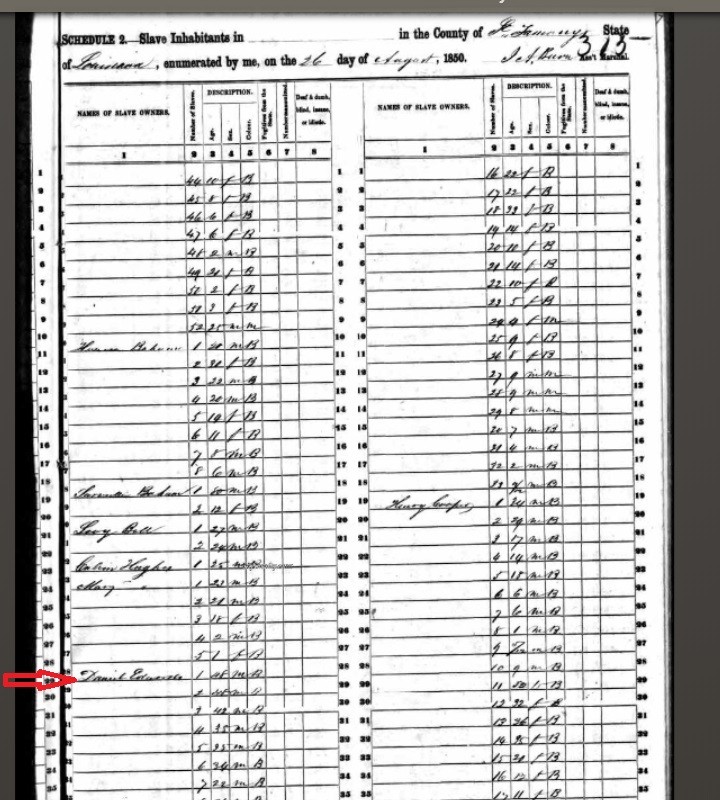

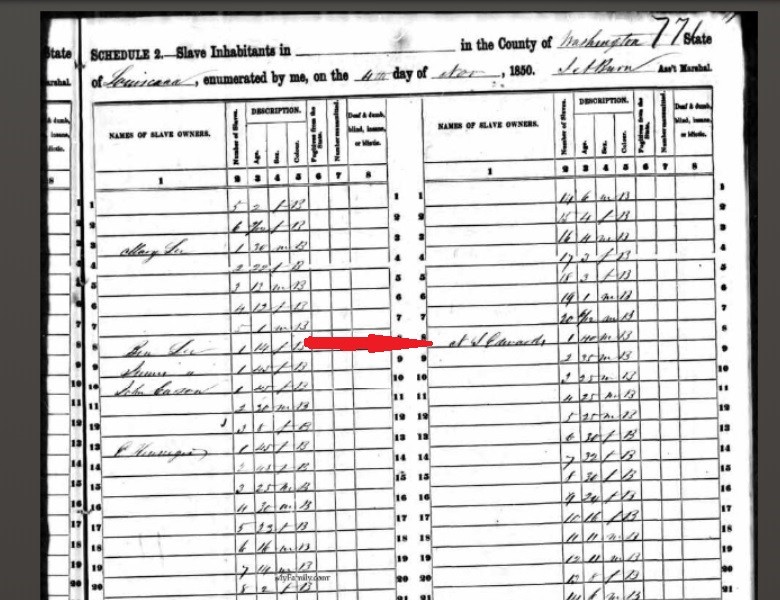

The 1850 U.S. Federal Census – Slave Schedule shows that Edwards’ great-great-great grandfather Daniel Edwards, a resident of St. Tammany Parish, Louisiana, owned 26 slaves. That same census showed that Daniel Edwards’ son, Gov. Edwards’ great-great grandfather Nicholas Stone Edwards, a resident of nearby Washington Parish, Louisiana, owned 33 slaves. Daniel Edwards and his son Nicholas Stone Edwards owned a combined 59 slaves in 1850.

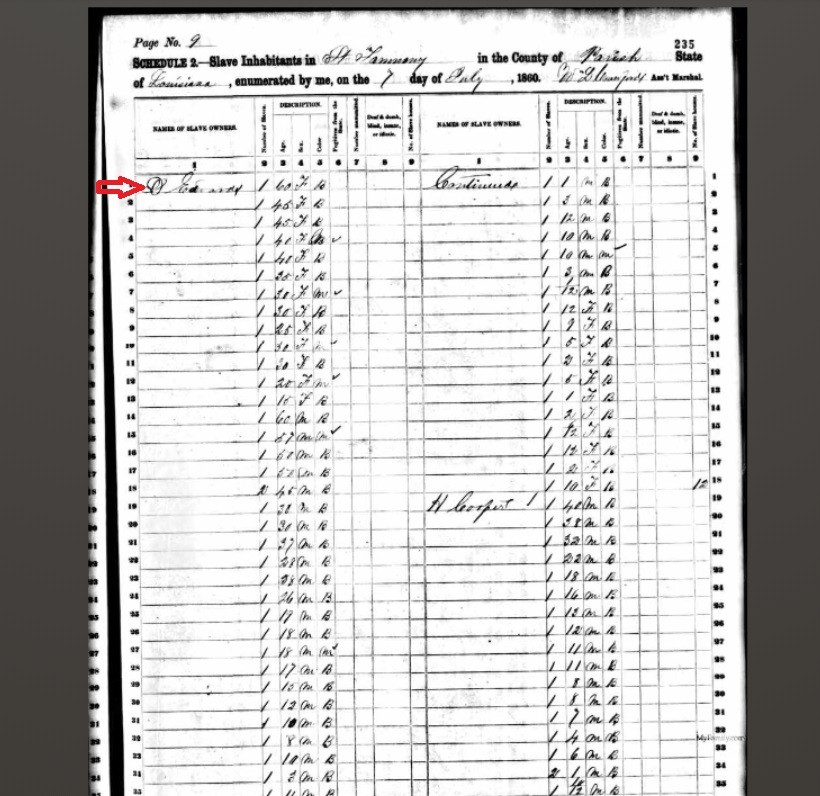

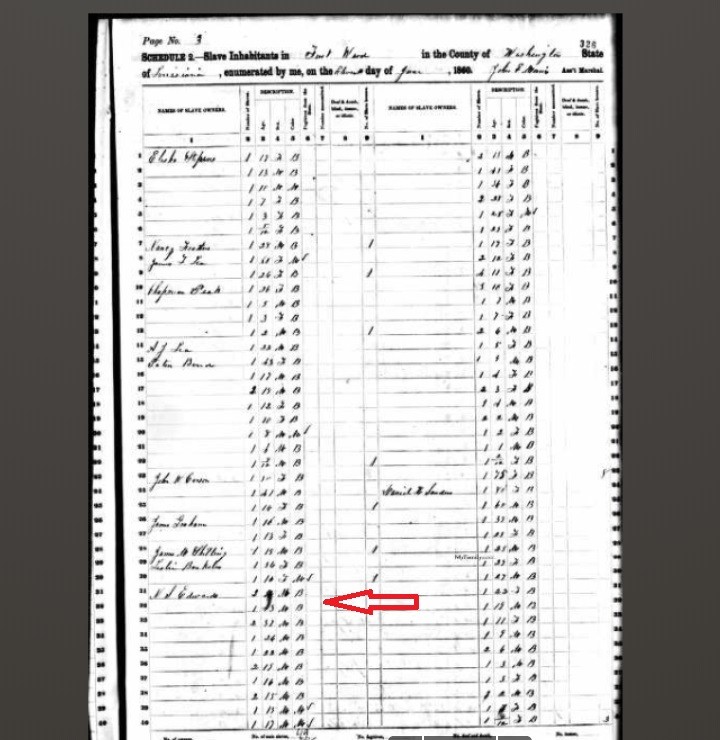

The 1860 U.S. Federal Census – Slave Schedules shows that Edwards’ great-great-great grandfather Daniel Edwards, a resident of St. Tammany Parish, Louisiana, owned 57 slaves. That same census showed that Daniel Edwards’ son, Gov. Edwards’ great-great grandfather Nicholas Stone Edwards, a resident of nearby Ward 1 in Washington Parish, Louisiana, owned 33 slaves. Daniel Edwards and his son Nicholas Stone Edwards owned a combined 90 slaves in 1860.

The Edwards family was one of the largest slave holding families in Louisiana in 1860, and was near the top one percent of slave holding families in the entire country at that time, according to data provided by the U.S. Bureau of the Census, Historical Statistics of the United States, 1970.

In 1860, there were about 22,000 slave holders in Louisiana. Only 547 owned more than 100 slaves. There were about 390,000 slave holders in the country, of which about 2,300 owned more than 100 slaves.

In 1869, during the Reconstruction period, a new parish, Tangipahoa Parish was organized from parts of St. Tammany Parish, where Gov. Edwards’ great-great-great grandfather Daniel Edwards lived at the time, and Washington Parish, where the governor’s great-great grandfather Nicholas Stone Edwards lived.

The Edwards family has played a prominent role in the politics of Tangipahoa Parish ever since.

In 1898, Millard Fillmore Edwards, the son of Nicholas Stone Edwards and great-grandfather of John Bel Edwards, served as Sheriff of Tangipahoa Parish.

From 1928 to 1948, Frank Millard Edwards, Sr., the son of Millard Fillmore Edwards and grandfather of John Bel Edwards, also served as Sheriff of Tangipahoa Parish. From 1956 to 1960 he served in the Louisiana State Senate.

The governor’s father, Frank Millard Edwards, Jr., served as Sheriff of Tangipahoa Parish from 1968 to 1980.

During the era of racial segregation in Louisiana, Edwards’ father, grandfather, and great-grandfather were key political players in Tangipahoa Parish, as the Times noted:

While in Baton Rouge, in 1956, Frank Millard Edwards voted for legislation that would have kept state schools segregated in violation of the Supreme Court’s landmark Brown v. Board of Education decision, which mandated segregation at all athletic and “public” events such as dances, and required white teachers for white students.

Another bill that earned Frank Millard Edwards’ approval would have classified donated blood. In July 1958, records show, the governor’s grandfather voted for legislation that would have required donated blood to be labeled “Caucasian,” “Negroid” or “Mongoloid” to indicate the race of the donor and require blood recipients to be informed of its origin except in emergencies.

While Gov. Edwards is accountable for his own actions, and not those of his ancestors, it is clear that his “family tradition” is different than the philosophy of hope, opportunity, and prosperity he continues to articulate as one of his key campaign themes.

Democrats, whether they support or oppose reparations, appear to be willing to give Edwards a pass on the issue.

What remains to be seen is whether or not Edwards’ family tradition will have an impact on the outcome of the October 12 “jungle primary” gubernatorial election.

Recent polls indicate that Edwards remains just shy of the magic 50 percent needed to avoid a runoff, while his two Republican opponents are vying to see which will make it into second place and a potential runoff election.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.