Democrats Talk Tough

Rep. Joe Kennedy III, Democrat of Massachusetts, got right to the point when he tweeted on September 19, “If he holds a vote in 2020, we pack the court in 2021. It’s that simple.”

Kennedy was saying that if Donald Trump nominates a candidate for the Supreme Court vacancy left by the death of Ruth Bader Ginsburg this year, then next year the Democrats will expand the court and pack it with liberals and progressives—if, of course, they get back in charge.

“Packing the court” is a loaded phrase, reaching back to a failed Democratic effort to expand the court in the 1930s. Indeed, that experience nine decades ago was so disastrous for the Democrats that, if they knew their own history, they would be fleeing from the phrase “court-packing,” not embracing it.

Yet, in fact, even before Ginsburg’s death, many leading Democrats, including Pete Buttigieg, spoke loudly in favor of packing the court, and Kamala Harris, when she was running on her own for the White House, said that she was at least “open” to the idea. Indeed, today, the Democratic Party’s top leaders, including Nancy Pelosi and Chuck Schumer, have indicated that “nothing is off the table” if Trump moves ahead to replace Ginsburg.

In other words, the Democrats could be on the cusp of another court-packing debacle, akin to that of the 30s. So maybe we, too, should know more.

Hubris and Nemesis

As is so often the case, disastrous failure comes after enormous success, as reckless arrogance overtakes prudential judgment.

That’s what happened to Franklin D. Roosevelt in his second term in the White House. On November 3, 1936, the 32nd president won a smashing reelection victory, defeating Republican challenger Alf Landon by more than 24 points in the popular vote, carrying 46 of 48 states; it was the biggest electoral landslide since 1820. In addition, FDR had long “coattails” to help down-ballot candidates; when the 75th Congress convened in January 1937, Democrats boasted a whopping 333 seats in the House and an even more whopping 76 seats in the Senate.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt, accompanied by his son, Franklin Jr., casting his vote at the Town Hall, at Hyde Park in New York, during the presidential election on November 3, 1936. (AP Photo)

Thus it’s easy to see how such a victory could go to one’s head. As John T. Flynn, a contemporary—and fierce—critic of FDR, wrote of the reelected president:

He was in a gay and triumphant mood. A naturally vain man, the tremendous victory at the polls had swollen his ego enormously. Few men in public life have ever received such thunderous applause or been surrounded by so many flatterers.

It was in this flattered-up state of mind that Roosevelt set about settling some scores. Most notably, he knew that the U.S. Supreme Court had been an obstacle to his agenda; in his first term, the high court had invalidated several New Deal laws. In fact, FDR had used the court as a foil during his reelection campaign, inveighing against “nine old men” blocking progress—and the tactic had worked.

So now, as he looked forward to pushing further to the left in his second term, Roosevelt and his aides hatched a plan for fixing the Supreme Court—starting with changing that long-standing number of justices, nine. As Flynn wrote, “He became more cocky and . . . decided that he was going to punish certain powerful enemies who had defied him. To begin with, he was going to bring the Supreme Court to its knees.” Thus the court-packing scheme was drafted inside the White House, neglecting any advance consultation with the Congress that would have to approve it.

Then on February 4, 1937, just two weeks after he had been inaugurated for a second term, FDR summoned the Democratic congressional leadership to the White House and unveiled his plan: For each judge over the age of 70—on the Supreme Court or for any other federal court—the president would be empowered to name an additional judge. In the case of the Supreme Court, that would mean that the membership would grow to a maximum of 15.

This was a sweeping proposal, completely overturning 150 years of precedent. Indeed, the reaction among Roosevelt’s fellow Democrats was instantly negative. Rep. Hatton Sumners of Texas, chairman of the House Judiciary Committee, declared immediately afterward, “This is where I cash in my chips.” That is, he was a firm “nay.”

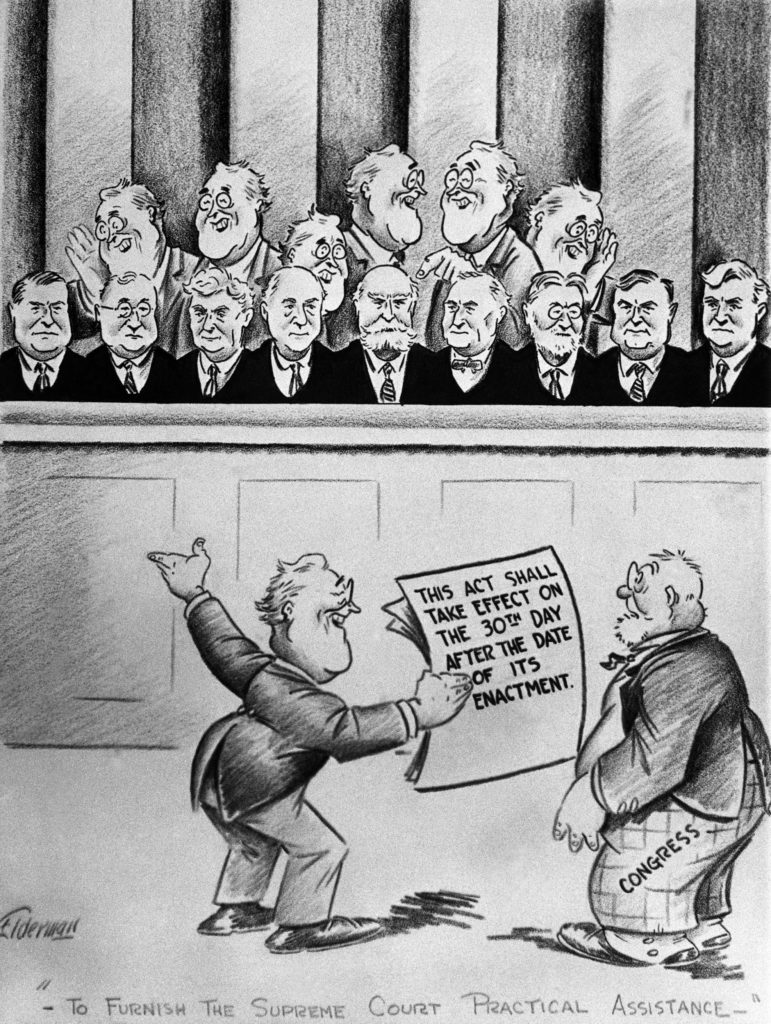

This February 6, 1937, editorial cartoon depicts President Franklin D. Roosevelt and the Supreme Court. (AP Photo)

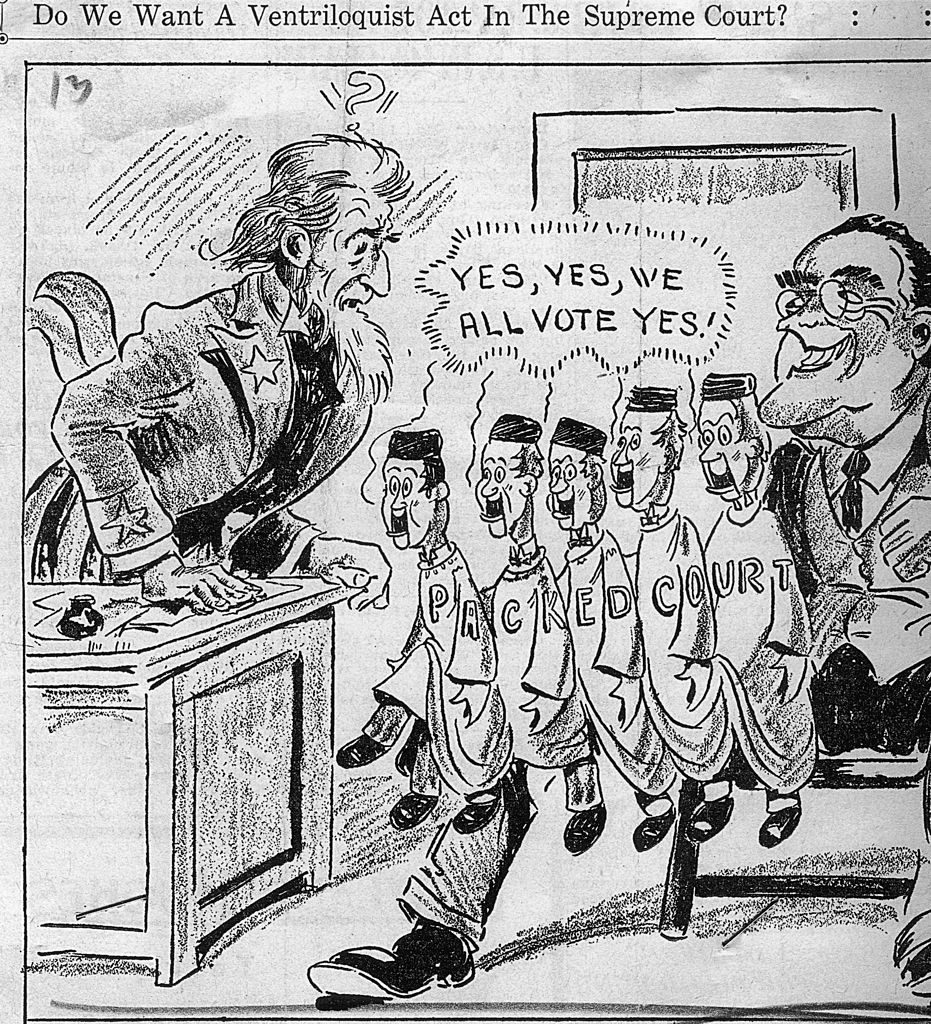

Editorial cartoon with the caption “Do We Want A Ventriloquist Act In The Supreme Court?” The cartoon, a criticism of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal, depicts the president with six new judges likely to be FDR puppets. February 14, 1937. (Fotosearch/Getty Images).

As a sympathetic political biographer of Roosevelt, James MacGregor Burns wrote later, “The proposal at the outset split the American people neatly in half.” Sharp-penned newspaper editorialists immediately labeled the plan “court-packing,” an ugly image somewhat akin to ballot-box stuffing. In fact, one of those editorialists, William Allen White, wrote that for the first time in his presidency, opposition to Roosevelt was coming “not from the [top] hat section but from the grass roots.”

Intriguingly, biographer Burns noted that FDR’s court-packing plan came at a time when even many Democrats who had voted for the president were now growing fearful that the Roosevelt administration was becoming too radical. In those days of energetic labor-union organizing, noisy and sometimes violent sit-down strikes were becoming common on factory floors; as Burns put it, the resulting unrest was “disturbing to people who wanted law and order.” (Yes, it’s interesting to see how that powerful phrase, “law and order,” keeps popping up across the decades.)

So we can see: FDR’s court-packing plan was losing altitude from its very launch.

Moreover, the president made matters worse with ill-chosen arguments, bespeaking a dismissive attitude toward hallowed constitutional traditions. For instance, during a “fireside chat” on national radio, broadcast March 9, 1937, Roosevelt described the executive, legislative, and judicial branches of the federal government as a “three-horse team,” arguing that all three horses should be “pulling in unison’’—and lamenting that one of them, the judiciary, was not pulling in unison.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt speaks into four radio microphones that sit on his desk during one of his live nationwide “fireside chat” broadcasts, circa 1935. (Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

Surely James Madison, principal author of the Constitution, would have been horrified to hear this out-of-left-field profaning of the careful checks-and-balances mechanism that he had included in our guiding national document.

In fact, hearing such unconstitutional argle-bargle coming out of the Oval Office, even Democrats normally supportive of Roosevelt and the New Deal grew alarmed. For instance, Sen. Carter Glass of Virginia—coauthor of the landmark Glass-Steagall banking-reform legislation that the president had happily signed into law just four years earlier—said that the court-packing plan was “completely destitute of all moral understanding.” And Jim Farley, then simultaneously the postmaster general and chairman of the Democratic National Committee—such “dual-hatting” was possible in those days—recorded that he was “amazed at the amount of bitterness engendered by the Court issue.”

In the meantime, Sen. Henry Ashurst of Arizona, chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee, used his convening authority to hold a Capitol Hill hearing on the court-packing proposal; Ashurst’s goal was to give a forum to the bill’s foes.

Indeed, Ashurst even went so far as to invite a non-member of the committee, the eloquent Sen. Burton K. Wheeler of Montana, to join the proceedings. Wheeler was normally a strong ally of FDR on domestic issues, and yet he was sufficiently alarmed at the prospect of “Caesarism”—that is, of a single man taking over too much power, as had Julius Caesar long before—that he rose in strenuous opposition to Roosevelt’s plan.

By July 1937, the court-packing plan was dead. It was a stunning defeat for the man who less than a year before had won such a resounding victory. Once again we are reminded of the wisdom of the ancient Greeks: Hubris begets nemesis.

However, FDR’s hubris wasn’t quite yet quelled. Angry over the failure of his court-packing plan, the president attempted to defeat, in Democratic primaries, some of his leading opponents—and once again, alert editorialists leaped to give this latest Rooseveltian stratagem a nasty name: They called it a “purge.” We might note that in those days, “purge” was a particularly fraught word, since over in the Soviet Union, Josef Stalin was overseeing a purge of his government, removing and executing thousands of fellow communists.

To be sure, it wasn’t fair to equate FDR’s attempt to defeat Democrats to Stalin’s decision to murder opponents—but nobody ever said politics had to be fair. The “p”-word, purge, stuck, and it further imprinted the fear that the Democrats were moving too far toward left-wing authoritarianism.

In other words, Roosevelt compounded a bad idea, the court-packing plan, with an even worse idea, an attempted intra-party purge. Interestingly, of the dozen candidates that FDR targeted, only one, Rep. John O’Connor of Manhattan, was actually defeated. All the rest—mostly in the South—survived, and they were now, unsurprisingly, not fans of FDR. Indeed, when one of the intended targets, Sen. Walter George of Georgia, heard the president joshingly described as “his own worst enemy,” George shot back, “Now while I am alive!”

For these and other reasons, the 1938 midterm elections were a disaster for the Democrats. The GOP gained a massive 81 seats in the House, as well as eight in the Senate. Indeed, beginning with the 76th Congress, Republicans and anti-Roosevelt Democrats joined together to create what became known as the “conservative coalition,” dominating Capitol Hill for the next quarter-century.

Roosevelt himself, of course, was reelected in 1940 and again in 1944. And yet the 1937 court-packing fiasco was a hinge in his presidency; he and the Democrats never again held sway as they had before.

So now, if we step back, we can see the potential parallels to our own time: If the Democrats win this year—and the RealClearPolitics polling average shows Biden in the lead—then the temptation to do everything possible to undo Trump’s presidency will be strong. And if Trump’s legacy were to include a replacement for Ginsburg on SCOTUS, well, the Democrats’ desire to pack the court to undo that “damage” could be overwhelming.

Yet if all that were to happen, the Democrats would be at great risk of overplaying their hand. Indeed, as the history of 1937 reminds us, many Democrats in Congress might not feel comfortable endorsing a blank check for the president—even a fellow partisan—to transform the judiciary. After all, if the president feels emboldened to transform the Supreme Court, what else might he seek to transform?

Wise heads in both parties know that our Constitution can be compared to a clock: A tinkerer might be able to remove a small piece or two with no harm done to the mechanism, but if too many pieces are removed, the whole thing breaks down—and it can’t be fixed.

Court-Packing Today

Interestingly, one Democrat who opposed court-packing was . . . Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

In an interview with NPR on July 24, 2019, Ginsburg was asked about the various proposals circulating, even then, about packing the court. She answered, “Nine seems to be a good number. . . . I think it was a bad idea when President Franklin Roosevelt tried . . . I am not at all in favor of that.”

She continued, “If anything would make the court look partisan, it would be that—one side saying, ‘When we’re in power, we’re going to enlarge the number of judges, so we would have more people who would vote the way we want them to.’”

Ginsburg’s caution notwithstanding, some Democrats, such as Joe Kennedy III, insist that the “crisis” of Trump’s judges—especially if he gets a third nominee on the court, in addition to Neil Gorsuch and Brett Kavanaugh—requires immediate and abrupt action in response. Speaking for his party on September 21, CNN’s Don Lemon was doing just that, when he said, as caught by Breitbart News’s John Nolte, “If Joe Biden wins, Democrats can stack the [Supreme] Court.” In the meantime, other elements of the Main Stream Media are filling heads with pure partisan vitriol, indistinguishable from that which comes from the Democratic National Committee, such as this Washington Post headline from September 22: “Democrats, it’s time to get mad—and even.” Out of such amped-up urgency, rash and foolish decisions are often made.

In fact, warning sirens are already being sounded on the left. For instance, Sen. Dianne Feinstein (D-CA), says that she opposes expanding the Supreme Court; interestingly, if the Democrats win the Senate this year, she’ll be the chair of the Judiciary Committee next year—and that’s the exact same post that Sen. Ashurst of Arizona used to block FDR’s court-packing plan back in 1937.

And on September 22, The Daily Beast reported that while Senate Democrats were feeling “acute pressure” to embrace court-packing, a grand total of one Democratic senator (out of 47) supports court-packing. Moreover, the article explains, such embracing “backs Democrats into the fight that Republicans want to have.” That is, the Democrats are at risk of extending themselves into avant-garde ideological territory they can’t defend—and leaving themselves open to a Republican ambush.

Moreover, independent journalist Michael Tracey, a gutsy left-winger aligned with Bernie Sanders, tweeted that would-be court-packers were undermining one of their favored criticisms of Trump, namely, that he is violating “norms”:

Court-packing would indisputably violate a key “norm” of American governance, with “norm violations” supposedly having been the main existential threat of the Trump presidency. Perhaps the whole “preserving norms” rhetoric was just a cover to make anti-Trumpism seem extra noble.

In other words, even if the Democrats like to say that Trump is abnormal, Tracey counsels them that it’s a mistake for them to be abnormal, too—and court-packing is abnormal. And we might note that in reality, Trump picking a conservative judge is, in fact, perfectly normal; that’s what conservative do.

So we might consider Tracey’s tweet to be a distant early warning for the Dems; that is, if they are fighting what they perceive as Trump’s abnormality—what others would, in fact, call normality–with their own abnormality, that could could be a huge mistake.

Why? Because in 2020, as in 1937—as in any year—most people in this country prize normalcy. And so as to court-packing, a Rasmussen poll from March 2019 found that by a nearly 2:1 majority, Americans opposed court-packing. Those numbers might have changed in the fever pitch of this moment, but it’s likely that if the Democrats were to win this November and were actually to propose a court-packing bill, they would, soon enough, suffer the same sort of cold reaction that FDR’s bill suffered back in 1937. Once again, it’s the reassertion of normalcy: Normal people want normal.

Even so, it’s possible that the Democrats are so revved up that they won’t be able to stop themselves from making a mistake—and that could even hurt Joe Biden’s prospects this November.

For instance, on September 21, Breitbart News reported that Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez declared that if the Democrats truly wish to stop Trump’s Supreme Court appointment, they should consider impeaching him (again), along with Attorney General William Barr.

Okay, so maybe we’re used to AOC saying fringe-y things, but in this case, she was speaking at a joint press conference with Senate Minority Leader Schumer. We can observe that while Schumer didn’t endorse what AOC said, he also didn’t un-endorse her words. And as we have seen, Schumer has asserted, “nothing is off the table.”

So do Democratic leaders really want to go through another impeachment? Of course not—that’s why you never hear Joe Biden talking about impeachment, nor does he wish to talk about court-packing.

Still, the party’s leaders, egged on by the base, might yet have their hand forced; that is, the activists could get so carried away with their own Trump-phobia that they provoke the party to do something stupid. They could impeach Trump, or Barr—some have even suggested impeaching Brett Kavanaugh!—and they might endorse court-packing as well. The possibilities for misplays, even before the election, are endless.

We began by recalling the swelled head that Franklin D. Roosevelt suffered in the wake of his monster reelection victory in 1936. There’s no way that Joe Biden could win that big in 2020—if he wins at all.

Yet as Mark Twain said, history might not repeat itself, but it often rhymes. And so that sound we hear all around us today could be the rhyming of Democrats as they take up an idea—court-packing—that even their secular saint, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, strongly opposed. That might seem to be a strange way to honor Ginsburg’s memory, but as we know, these days, many Democrats are acting strangely, as if they have forgotten their own history.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.