Most native-born American photojournalists have been elbowed out of the Hollywood paparazzi business by an immigration wave of lower-wage, lower-status, illegal-immigrant photojournalists, according to a California academic and media reports.

The native-born Americans were largely replaced because of “the willingness of these Latino laborers to work around the clock in a line of work that is publicly denigrated,” said Vanessa Díaz, an anthropologist at the University of California. She estimates that only about 4 percent of paparazzi are “white,” but did not say what percentage are American, according to the Fusion news site.

Díaz did not respond to emails from Breitbart News.

The inflow of illegal immigrants eager to pursue celebrities for candid street photographs was so great that they cut their own paparazzi wages, according to a Fusion report, which summarized the trend:

Now, when the photographers are waiting for celebrities to make an appearance, they’re almost always speaking in Spanish. Or Portuguese, according to Galo Ramirez, who started working in the industry at 24 and was a full-time celebrity photographer for more than a decade. “I was pretty young when I got the job and there was a certain kind of excitement,” Ramirez, who was born in El Salvador and moved to California when he was six years old, told Fusion.

When Ramirez, who is now 36 and a U.S. citizen, started working as a paparazzo, photographers could make anywhere from $10,000 to $20,000 a month. That’s huge, especially considering that the average Latinx who attended some college make about $2,756 per month working full-time, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.…

Ramirez says the pay isn’t as significant these days, which is why he is no longer working in the industry. He wouldn’t say what he’s doing for work now, but said being a paparazzo was not a good living.

The article also quotes freelancer Jose Gonzalez, who “came to the U.S. in 1987 from El Salvador and now lives in Los Angeles with his two children.”

The rarity of native-born Americans in the business is unusual. In nearly all job sectors tracked by the federal government, native-born Americans outnumber immigrants, even in lower-status jobs such as maids, janitors, and taxi drivers. The only sector where native are outnumbered by immigrants is in agricultural manual labor, where immigrants comprised just 50.7 percent of the workforce in 2014, according to the Center for Immigration Studies.

Still, immigrants — both legal or illegal — do hold large shares of several white-collar job sectors, including 26 percent of computer programmers, 19 percent architects and engineers, 27 percent of doctors and surgeons, and almost 5 percent or reporters [including this reporter]. Many of these U.S.-based foreign professionals arrived via legal contract-worker programs, such as the H-1B visa program.

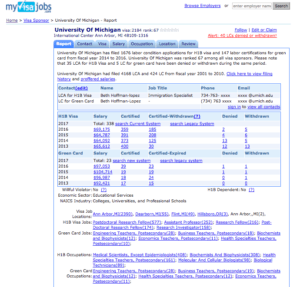

Diaz, the academic, is facing the same outsourcing pressures because many universities are importing cheap-H-1Bs instead of hiring Americans. Those outsourcing universities include her alma mater, the University of Michigan, and her current employer, UCLA. The two universities have requested visas for more than 1,500 foreign professionals since 2013.

Journalists are also facing the same outsourcing pressure amid a huge job-loss in the print sector and industry-wide salary declines.

In 2016, companies used the H-1B program to seek visas for 254 foreigners to work as reporters and 551 foreigners for “editor” jobs, according to MyVisaJobs.com. Additional media employees – including reporters, camera operators, and graphics designers — can be hired or imported via the L visa and the Optional Practical Training programs.

Immigrant numbers will likely accelerate in some white-collar job sectors because fewer Americans seek employment in job sectors dominated locally by immigrants. Incumbent managers, such as hiring managers at firms which use many H-1B workers, tend to hire their peers, exclude native-born Americans, speak foreign languages and also to lower the social status of their jobs among native-born Americans.

Those pressures accelerate the changeover in the Hollywood paparazzi business, where the estimated 500 paparazzi recruit their peers, said Díaz. “The jobs that Americans don’t want are not just those that are too menial, but also jobs that are too stigmatized,” she told Fusion.

Díaz’s research on the numbers, wages, and status of illegal-immigrant Hollywood paparazzi are backed up by comments from employers. In 2008, after almost eight years of lax immigration-enforcement by President George W. Bush, the Associated Press reported:

“There’s a lot of illegals out there, and X17 has a lot of them,” said [Gary] Morgan of Splash [News]. Francois Navarre [co-founder of X17] has said that many paparazzi are in the process of becoming legal immigrants. “It used to be all white guys,” [JFX co-founder Arnold] Cousart said. “Now it’s like ‘We Are The World’ out there.”

Veteran paparazzi like Frank Griffin, who runs the Bauer-Griffin agency, complain that the new LA shooters know nothing about their cameras or subjects. “I call them knuckle-scraping mouth breathers,” Griffin said. “They can either make $1,500 a month running around with cameras, or they can go rob a 7-Eleven.”

“We see them as the scourge of the problem,” Cousart said in one breath, before acknowledging in the next that his guys join in the scrum: “We’ve got to play or we’re going to starve.”

One of the remaining native-born Americans in the business is 10-year veteran Rick Mendoza. In 2015, he described his career to Los Angeles Magazine:

I was born in El Sereno, which is recorded as the oldest community in L.A. I’m a true Angeleno. I lived there until I was seven or eight. The San Fernando earthquake happens in 1971, and my mother says, “I don’t like L.A. anymore.” Her family is in Arizona, and she thinks it’s a lot wiser to be closer to my grandmother instead of earthquakes, so we’re on our way to Tucson. I took photography classes in high school. Mr. Montgomery at Pueblo High taught media communication. He opened my eyes to video and media; I loved it. I thought, “Hey, maybe one day I could do weddings, you know, proms—anything that had a celebration that people wanted memories of.”

… I love L.A. Besides it being my home, my birthplace, it’s the entertainment capital of the world. I’m a “candid street celebrity photographer.” I have a 5D Mark III Canon, a 7D Canon, and a 40D Canon. My work goes to legit sources—magazines like Cosmopolitan and New York, Web sites, blogs, and entertainment shows. I’ve been interviewed on Katie Couric. I’m published almost on a daily basis—more than most writers.

There’s no steady income in the business, partly because there are so many photographers vying for valuable pictures, Mendoza said.

In L.A. there could be as many as 500 paparazzi. We have no union, no hours, nothing that helps us in any way. Nothing. No one has our back. You get the shot or you don’t eat. You have to be creative and aggressive and think two steps ahead of the celebrity, think five steps ahead of your fellow paparazzi and whoever else is in the area. There’s the general public, who all have their little smartphones, and there are the looky-loos, who just want to see what’s going on—they’re all in the way. There’s no street justice. If you don’t think fast, someone is gonna be in your way and you won’t get the shot. Someone else is gonna shoot it. I made $8,500 last month. Some guy made $700. Some guy even lost money.

Diaz began her research when she was working as a reporter in Los Angeles for People magazine, she said in an interview.

As a celebrity reporter, I always noticed that most of the reporters were women, but then I also noticed most photographers—both red carpet and [street] paparazzi—were men. This dichotomy of demographics within the production of celebrity also sparked my interest. I also began wondering why the paparazzi were predominantly Latino, and how this demographic fact might affect the ways in which the profession is treated.

Diaz talked about her research at an April 18 event at UCLA. According to the invite, which was headlined “The Latino paparazzi of Los Angeles: Life, death and labor in the celebrity industrial complex”:

Join the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center for a special research presentation by UCLA Institute of American Cultures visiting researcher and Ford fellow Vanessa Díaz, who will explore the racial politics of representation and division of labor among paparazzi from 4 p.m. to 6 p.m. on Tuesday, April 18, in Haines Hall, room 144.

In the last fifteen years, the demographics of the Los Angeles paparazzi transitioned from a labor force of predominantly white men to one of predominantly Latino men, including individuals born in the U.S. and Latin America.

Read the Fusion article here.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.