By the time 1942 rolled around, three things had happened that would result in one of the greatest runs of horror films in Hollywood history. The first was that thanks to “boy genius” Orson Welles, RKO was staring into the abyss of bankruptcy. Today, Citizen Kane (1941) and The Magnificent Ambersons (1942) are rightly regarded as masterpieces. But, at the time, RKO saw them as expensive financial failures that came with a side order of PR headaches.

Second, across town at Universal Studios, fortunes were being made from modestly-budgeted horror films with titles like The Wolf Man (1941), The Mummy’s Hand (1940), and Son of Frankenstein (1939).

Third, a talented and driven man grew tired of working for his own “boy genius.” After nine years of long hours with independent producer David O. Selznick, longer reading assignments (the length of Selznick’s memos remain legendary), and not enough credit or opportunity for advancement, story editor Val Lewton was ready to produce his own films.

Lewton was born Vladimir Ivanovich Hofschneider in 1904 in what is now called Ukraine. His family came to America in 1909 and converted from Judaism to Christianity. Although Lewton would not become a naturalized American citizen until 1941, by that time, he had already written successful pulp novels, worked in MGM’s publicity department, and come to the attention of Selznick. Sadly for Lewton, although he was a very good story editor (you had to be to remain employed by a tireless perfectionist), his legend during those years is remembered as The Man Who Told Selznick Making Gone with the Wind Was a Mistake.

And so, in 1942, Lewton moved to RKO for $250 a week as a full-fledged producer. The studio said his budgets would have to come in under $150,000, his runtime would have to come in under 75 minutes, and he must use titles such as Cat People, and I Walked with a Zombie.

Oh, and he had better make money, or else.

Other than that, RKO left Lewton alone to make his movies, and the results saved the studio from bankruptcy and resulted in a run of timeless films that still entertain, provoke, and chill.

The first, Cat People, would set the stage for eight more Lewton B-films written, directed, scored, and shot by A-list talent. These classics employed noir (two years before anyone else in Hollywood), understatement, sound design, and complicated themes to crawl under our skin.

Here’s a rundown in the order they were released:

—

Cat People (1942)

Imagine you’re a producer with a $150,000 budget (about $2.75 million today) and stuck with a title like Cat People. A terrible producer would try something like this. Lewton immediately understood that actors running around in cheap cat costumes would not only fail at the box office but kill his chances at someday producing A-pictures.

What to do? What to do?

Well, what he did would set a template for his next eight movies and psychological thrillers straight through to today: he let the audience do the work. We never see the doomed Irena (Simone Simon) change into a black panther. Instead, we see shadows, hear growls, and watch the face of the person being stalked. We fill in the blanks in our minds, which saved RKO thousands in special effects.

But Lewton also tells a grown-up story. Cat People is about sex. The kids will never pick this up. The adults, however, understand that passion turns Irena into a deadly panther, and nothing rouses her passion like jealousy. So you can imagine what happens when Irena’s sex-starved husband (Kent Smith) falls in love with another woman.

With genius director Jacques Tourneur at the helm, Nicholas Musuraca’s breathtaking black and white photography, the RKO backlot, and RKO’s talented contract players, Lewton was a true maestro delivering a tense story filled with thematic depth and atmosphere to spare.

Cat People saved RKO with its eventual gross of over $4 million.

Paul Schrader’s 1982 remake had plenty of money, explicit sex, and big stars — including a stunning Nastassja Kinski. It stinks.

Highlight: The swimming pool scene is still a classic.

—

I Walked with a Zombie (1943)

Before Cat People had hit theaters, Lewton and Tourneur were creating a miracle turning the RKO backlot into the Caribbean island of San Sebastian, a place filled with history, foreboding, death … and zombies!

I Walked with a Zombie is my second favorite Lewton film. It tells the story of Betsy Connell (Frances Dee), a beautiful young nurse sent to a Caribbean island to care for the wife of the brooding and fatalistic Paul Holland (Lewton regular Tom Conway; brother of George Sanders). Holland’s wife suffered an accident that gave her a zombie-like quality. She looks perfectly healthy but exists like a sleepwalker.

What makes this story work is the extraordinary ambiance and heavy (but not heavy-handed) themes about adultery and the legacy of slavery. This is one of those movies that offers something new with each viewing.

Highlight: That moonlit walk through the sugar cane fields.

—

The Leopard Man (1943)

Another ridiculous title foisted on Lewton and Tourneur that they turned into near-gold. My least favorite of the Lewton Nine is still pretty great.

Thanks to a desperate public relations stunt, a black leopard is released into a small town in New Mexico. People start to die, and the couple responsible for the leopard’s escape — nightclub promoter Jerry Manning (Dennis O’Keefe) and his singer/girlfriend Kiki Walker (Jean Brooks) — are forced into a terrible position. The first is the guilt they feel over all those deaths. The second is the sense that the leopard might not be responsible.

Leopard Man is one of the first movies to examine the psychology of a serial killer.

Highlight: The scene under the bridge.

—

The Seventh Victim (1943)

After editing the previous three, Mark Robson was brought on as full-fledged director for this stunning tale of a beautiful woman caught in the grips of an urbane group of Satan worshippers.

The first half is somewhat marred by several scenes that were inexplicably cut. The result is a choppy plot where the viewer is asked to fill in too much. However, the way this sucker wraps up is a true jaw-dropper that stays with you for days.

In her screen debut, Kim Hunter is Mary Gibson, an innocent young woman whose older sister Jacqueline (doomed, alcoholic actress Jean Brooks) has gone missing. Frantic, she returns to New York. There she discovers her sister sold a successful cosmetics company, employed a psychiatrist (Tom Conway again), and secretly married Gregory Ward (Beaver’s dad Hugh Beaumont). Things get really weird when Mary opens the door to Jacqueline’s rented room to find only a noose hanging from the ceiling.

Once again, Lewton dabbles in big themes, especially nihilism’s corrosive and tragic effects on the human spirit and the existential dread of death that haunts narcissists and shallow pleasure seekers.

He also gave Hitchcock a pretty good idea about how vulnerable we are in the shower.

Highlight: The closing moment. Wow. How Lewton got that past the Production Code is beyond me.

—

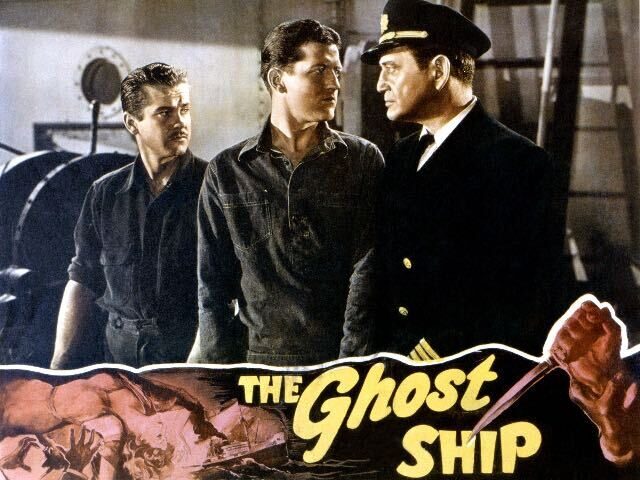

The Ghost Ship (1943)

Lewton’s fourth — fourth! — movie of that year is a true stunner. Mark Robson returns to direct, and Nicholas Musuraca delivers an Oscar-worthy piece of black-and-white cinematography that only ever utilizes a single light source. This genius effect crawls right under your skin.

The monster in Ghost Ship is Richard Dix, a former A-list star dulled by middle age and drink. He plays Will Stone, the captain of a merchant vessel who takes on a new third officer, Tom Merriam (Russell Wade).

At first, Tom admires his captain, who takes the young man under his wing, trusts him with authority, and mentors him with philosophical discussions. Then Tom realizes Stone is a murdering sociopath, but no one else will believe him.

Atmospheric from top to bottom, suspenseful, and beautifully acted by Dix.

Highlight: That massive hook.

—

Curse of the Cat People (1944)

A fascinating sequel, primarily because it’s so different from the original.

Cat Person Irena died in the first film but returns here as the “imaginary friend” of Amy, the six-year-old daughter of Irena’s widowed husband and his new wife.

As Amy, Ann Carter is a child-acting wonder, utterly believable and natural in every scene, without any of those annoying affectations too many child actors deliver today. Amy is not an adult in a child’s body. Instead, she’s all six-year-old, and that is what makes the story work.

This movie is about alienation, the poison of holding grudges, and the miracle that comes with offering another grace. Much of it is set during Christmas, and the atmosphere created with no budget on a backlot is unforgettable.

Highlight: Amy embraces a bitter woman with murder in her eyes.

—

The Body Snatcher (1945)

My favorite of the nine.

Fate, again, was kind to the movie gods. 1) RKO decided a horror star would boost profits. 2) The Mighty Boris Karloff was tired of being layered in makeup. 3) Val Lewton had no desire to make monster movies.

Both men were initially wary of the other, but what followed was a lifelong friendship and three terrific movies, starting with the Body Snatcher, which is not only a horror masterpiece and Lewon’s best film, it gives us Karloff’s greatest performance.

Lewton promoted future two-time Oscar Winner Robert Wise from the editing room to make his directorial debut with Curse of the Cat People and wisely brought him back for this deliciously nasty story of a doctor with a past and the man who blackmails him.

Set in 1831, Dr. Wolfe “Toddy” MacFarlane (a never better Henry Daniell) is an esteemed spine surgeon who also runs a surgical school. MacFarlane takes Donald Fettes (Russell Wade), his most promising pupil, under his wing. But surgical skill is only part of that mentorship. There’s also reality, which means sometimes bending the rules to ensure the cause of medicine advances.

Enter John Gray (Karloff), the body snatcher in question. To keep the school in cadavers, Gray robs fresh graves. Once this becomes too difficult, he launches a killing spree.

MacFarlane is horrified by Gray’s murders but can do nothing. Gray knows all of MacFarlane’s secrets and shamelessly and gleefully blackmails him.

Karloff delivers what I would call a Movie Star Performance. He is stunning as the oily, charming, sinister, funny, menacing, likable Gray. His every scene is a dazzler, especially his showdowns with Daniell.

Bela Lugosi, whose career was going downhill fast, creeps around in the background and has a fantastic scene with Karloff in their seventh and final time together as co-stars.

Highlight: The murder of the blind street singer.

—

Isle of the Dead (1945)

Mark Robson returns as director in this chiller about a group of strangers forced to wait out a plague on an island that serves primarily as a graveyard.

Karloff enjoys the juicy role of a hardened general open to superstition. It’s his job to ensure no one leaves the island and infects the general population. But he is also taken in by an old woman who believes a young woman is a Vrykolaka, something close to a vampire.

People begin to die off, one is buried alive, and tensions explode as the plague runs its course.

Highlight: Did I mention someone is buried alive?

—

Bedlam (1946)

The year is 1761, and Karloff once again steals the show as Sims, the sadistic administrator of an insane asylum pitted against Nell Bowen (Anna Lee), a willful woman committed to reforming that asylum.

Here the horror comes from the terrifying reality of how the mentally ill were mistreated and exploited (including sexually) in these institutions.

As Nell, Anna Lee is utterly believable as a high-class prostitute who grows a social conscience against her will. She’d like nothing more than to go on with a life filled with pretty things and fine dining. But she can’t unsee what she saw and then there’s the Quaker Hannay (Richard Fraser), who refuses to let her off the hook. Without being off-putting or smug, Nell becomes determined to reform, even if it costs her everything — and it does.

A remarkable movie filled with effortless plotting and thematic depth.

Highlight: That first look at the asylum.

—

When you’re talking about Hollywood some 80 years ago, you’re talking about an industry that portrayed racial minorities in a demeaning, condescending, and stereotypical way. There are exceptions, and Lewton was a notable one. Today’s fascist woketards might still find a reason to nitpick, but knowing how black and Hispanic characters were treated on film in those days and watching how Lewton portrayed them is startling in its contrasts.

In The Cat People, a black woman owns a café frequented by a young couple. She’s not only a business owner but there are no yessums or sassy mammy talk. Instead, she sounds like what she is, an educated and accomplished woman, an equal to her customers.

The Leopard Man spends most of its focus on the Hispanic population of New Mexico. Non-whites, including the Mexican actress Margo, play most of those roles and the culture is in no way demeaned with the era’s stereotypes: lazy drunkenness, etc.

I Walked with a Zombie is ripe for stereotypical exploitation. The entire story revolves around the island’s black population and voodoo. Lewton not only treats his black characters with dignity, but voodoo itself is portrayed thoughtfully and realistically, as opposed to dark-skinned savages menacing virginal white women. This includes Carre-Four (Darby Jones), the terrifying black zombie who eventually is seen as a symbol of pity.

Additionally, the horror of slavery is Zombie’s thematic undertow. In an early scene, a black cab driver tells our heroine about the island’s history, how African slaves were brought to San Sebastian in chains. Her flippant response — “They certainly brought you to a beautiful place” — might sound like 1940s Hollywood wrist-flicking slavery. The truth is that she and we are about to get a lesson, but not a smug lecture like we would today. Instead, it’s all in the haunting subtext, which will make you want to immediately rewatch this classic.

The Trinidad-born Sir Lancelot (real name Lancelot Victor Edward Pinard) appeared in three Lewton films, notably The Ghost Ship, as one of the sailors. Despite his dark skin, he’s never treated any different and joins in on the non-stop teasing and needling between the men. Later, he’s seen punching out a white man, a German “heine” no less. Imagine what it meant to have a brown-skinned man punch out a German in the early days of WWII.

—

Despite his artistic and box office success, studio politics cost Lewton his job at RKO. After that, he found sporadic employment, but a heart attack and other health issues meant he would never produce another film. He died in 1951 at age 46.

The following year, Kirk Douglas would immortalize Lewton in The Bad and the Beautiful (1952), playing a lowly producer who takes over the town after producing a series of low-budget horror films decades ahead of their time.

Follow John Nolte on Twitter @NolteNC. Follow his Facebook Page here.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.