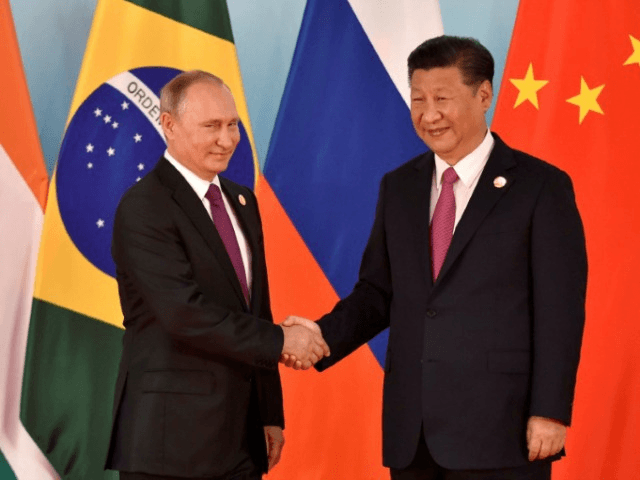

China’s state-run Xinhua news service reports that Chinese President Xi Jinping and Russian President Vladimir Putin met at the BRICS economic summit on Sunday and “agreed to appropriately deal with the latest nuclear test conducted by the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea.”

For the moment, the nature of that appropriate response can only be left to the imagination.

Xinhua portrays Xi and Putin agreeing to “consolidate the high-level mutual political trust, firmly strengthen mutual support and enhance strategic coordination,” with Xi throwing in a plug for Russian participation in China’s “One Belt, One Road” trade route mega-project. There was talk of cultural exchange and enhanced military cooperation.

However, aside from Xinhua making two broad assertions that Xi and Putin agreed to “deal appropriately” with North Korea and stay the course on denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula, there is little acknowledgement that Pyongyang is on the verge of starting either a cold or hot war that could ruin all of China and Russia’s regional ambitions. “One Belt, One Road” could quickly disappear into One Unholy Nuclear Mess.

It is rather fanciful for Xinhua to chatter about “denuclearization” when the entire point of Kim Jong-un’s latest nuclear test, besides cleaning up a few nuclear warhead research details, might have been formally notifying China that North Korea is now a permanent nuclear power, with the ability to strike on a regional or global scale. The fact that North Korea’s nuclear test was held during the BRICS summit, which is quite important to China, has been taken by some observers as a deliberate insult.

The BRICS nations—Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa—expressed “deep concern over the ongoing tension and prolonged nuclear issue on the Korean peninsula” in a draft communique on Monday, and are expected to repeat that call in a formal statement later. However, that is only one of several items on their joint agenda; they put equal emphasis on climate change. There is not much to indicate these nations collectively view North Korea as the defining crisis of the moment.

If U.S. President Donald Trump is serious about pursuing a trade embargo against every nation that does business with North Korea, all of the BRICS nations would be directly affected in a major way, except for South Africa. Africa in general has played a significant role in helping North Korea escape the effects of trade sanctions, and South Africa has some unpleasant political ties to the Kim regime going back for decades, so it would hardly be unaffected. It is hard to imagine anything that should be higher on the BRICS agenda than resolving the North Korea crisis.

That crisis developed in large part because Western politicians thought they could kick the proverbial can down the road for decades on end, collecting political points and quick hits of positive media coverage by announcing a series of landmark agreements that did exactly nothing to slow Pyongyang’s relentless march to nuclear missiles.

But it also developed because malevolent powers like China and North Korea were pleased to indulge the psychoses of the Kim dynasty, making use of North Korea as a mad-dog threat they could sell themselves as the only solution to, running what amounted to a geostrategic protection racket for three decades.

Both China and Russia liked the idea of their Pacific competitors diverting military and diplomatic resources into dealing with the constant North Korean threat. They also liked the way Pyongyang defied Western demands and made the American hyperpower appear impotent. It helped China and Russia sell their very different ideas of global stability to a market hungry for rational order.

It is vitally important for Beijing and Moscow to understand that those games are over now, forever. As U.S. Ambassador Nikki Haley put it to the U.N. Security Council on Monday, “We have kicked the can down the road long enough. There’s no more road left.”

“Enough is enough,” said Haley. “We have taken an incremental approach, and despite the best of intentions, it has not worked. … I think that North Korea has basically slapped everyone in the face in the international community that has asked them to stop.”

Haley took aim at China and Russia, without calling them out by name, when she said demands for the U.S. and South Korea to halt joint military exercises were an “insulting” attempt to shift blame for instability on the Korean Peninsula to Washington and Seoul.

China and Russia are keeping up their usual calls for “cool heads” and de-escalation, but they have already taken irrevocable steps to escalate the situation to its current boiling point. The world should have learned by now that economic warfare is the only substitute for military action when it comes to restraining rogue states with nuclear ambitions. By sabotaging the economic war against North Korea, Russia and China made military action more likely.

The surest sign both nations disagree with Ambassador Haley’s assessment of the shortage of road for further can-kicking is that Russia and China are basically competing for influence with Pyongyang, as part of their competing bids for hyperpower status.

They remain partners in the effort to end the American century and create the global power vacuum both aspire to fill. China seems a bit more irked with Kim Jong-un’s latest nuclear antics than Russia, but so far there is little sign either of North Korea’s major patrons is willing to employ the ultimate economic leverage that might actually adjust Kim’s attitude. For now, China and Russia still seem to view North Korea as an American problem, which means they still see it as a Chinese and Russian opportunity. Convincing them otherwise is both a tall order, and urgently necessary, for the Trump administration.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.