The simple truth of the opioid crisis is that prescription drugs have been blamed for a deadly crisis that is far more attributable to street drugs smuggled across the porous U.S. border.

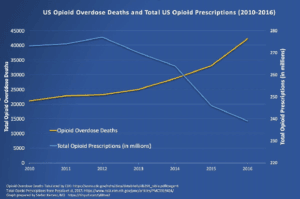

It’s blindingly obvious from the latest Centers for Disease Control data that opioid prescriptions have declined to levels from before the overdose crisis, while the death rate continues to climb. Congress and federal officials nevertheless proceed as if cracking down even further on prescriptions will solve the problem.

The CDC reports opioid prescriptions began increasing in 2006, peaked in 2012, and then began declining until it hit “the lowest it had been in more than 10 years.”

The CDC adds that prescription rates vary a great deal in different parts of the country, with some areas boasting rates seven times higher than the national average. “In 16 percent of U.S. counties, enough opioid prescriptions were dispensed for every person to have one.”

The timeline is especially clear when looking at a graph of overdose deaths versus prescription rates, a relationship that is now the reverse of where it stood at the beginning of the decade:

It should be noted that even those figures understate the degree to which street drugs have overtaken prescription medications as overdose killers because the CDC counts any death involving a user of prescription medications as prescription drug related, even if street drugs like heroin and fentanyl were also consumed by the victim.

Some of the confusion in our national drug policy stems from politicians lagging behind and focusing on a problem that was much more severe a decade ago. They are also basing national policy on an overprescription issue that is only a serious problem in certain cities and counties.

Unfortunately, politicians are also reluctant to tackle the real drug crisis because it makes the dangers of illegal immigration and weak border security painfully clear. They do want to go after prescription drugs because the companies that make them, and the doctors who prescribe them, have a great deal of money.

Betsy McCaughey of the London Center for Policy Research denounced the wave of lawsuits against the painkiller industry nothing less than a “shakedown” by “money-grubbing politicians” in an August op-ed at the New York Post:

Pinning the entire overdose crisis on drug companies is scapegoating. It ignores scientific evidence showing that the biggest cause of opioid deaths is illegal drugs like fentanyl and heroin trafficked to young people. Prescriptions for high doses of opioids needed for chronic pain are down 41 percent since 2010. Yet overdose deaths are higher than ever. Medical users aren’t the ones overdosing.

Harvard and Johns Hopkins researchers find a miniscule six-tenths of 1 percent of patients prescribed opioids after surgery misuse them.

Of the overdose victims who land in an emergency room, 89 percent aren’t pain patients, according to JAMA – Internal Medicine. They’re younger than typical pain patients, and they’re overdosing on stolen pills and street opiates. Blame pushers, not doctors and drug companies.

McCaughey described the jihad against prescription drugs as similar to the anti-tobacco crusade, with some of the same lawyers seeking big paydays:

For politicians, the lawsuits are about publicity for themselves and filling the public trough. For their accomplices, the trial lawyers, it’s personal gain. Politicians are selecting private law firms to handle these suits. If these lawyers win, they’ll become wildly rich, taking home 25-33 percent of every payout.

Several lead lawyers are veterans of the 1990s anti-tobacco litigation. The big difference this time is that opioid medications aren’t, by definition, coffin nails. Nine million Americans with chronic pain need these drugs to get through their days.

As to the actual problem, the political pressure is all moving in the wrong direction: weakening border security, stubbornly refusing to build a security barrier, backing away from stiff penalties for drug traffickers, letting drug offenders out of prison. The actions taken by America’s political class against the drug crisis is almost a perfect mirror image of what it should be doing.

Daniel Horowitz at Conservative Review noted on Monday that opioid legislation is almost entirely premised on prescription drug abuse as the major problem, while Congress refuses to acknowledge the drop in prescription rates or hold hearings about Central American drug cartels using gangs like MS-13 to distribute their deadly products in the United States. Even at that, a bill beginning with the assumption that pharmaceuticals are the problem ends up giving huge grants to Big Pharma for developing addiction-resistant medications, which keeps the industry quiet.

Of course, our politicized media isn’t making things any better. Reporters have settled on a narrative of prescription drug patients getting hooked and turning into hardcore drug abusers, actively seeking out such stories while downplaying information to the contrary. Journalists explicitly tell activists and doctors they are only interested in stories about drug abuse that began with prescription drugs. They downplay street drug abuse by individual subjects to portray them as victims of painkiller abuse.

Maria Szalavitz explains how the media narrative factory works at the Columbia Journalism Review:

Often, stories focus exclusively on people whose use started with a prescription; take this, from CNN (“It all started with pain killers after a dentist appointment.”), and this, from New York’s NBC affiliate (“He started taking Oxycontin after a crash.”)

Alternatively, reporters downplay their subjects’ earlier drug misuse to emphasize the role of the medical system, as seen in this piece from the Kansas City Star. The story, headlined “Prescription pills; addiction ‘hell,’” features a woman whose addiction supposedly started after surgery, but only later mentions that she’d previously used crystal meth for six months.

The “relatable” story journalists and editors tend to seek—of a good girl or guy (usually, in this crisis, white) gone bad because pharma greed led to overprescribing—does not accurately characterize the most common story of opioid addiction. Most opioid patients never get addicted and most people who do get addicted didn’t start their opioid addiction with a doctor’s prescription.

The result of this skewed public conversation around opioids has been policies focused relentlessly on cutting prescriptions, without regard for providing alternative treatment for either pain or addiction.

In truth, as Szalavitz pointed out, 80 percent of opioid addicts begin by taking street drugs or stealing prescription pills from friends and family members. The addiction rate for chronic pain patients stands at less than 8 percent overall and is even lower for the middle-aged and older patients who suffer from the majority of chronic pain issues. Unfortunately, the politicians and government officials entrusted with battling the opioid crisis are still prone to making blatantly false assertions that the majority of opioid addicts began with prescription drugs.

Those who seek to correct the record on the opioid crisis are careful not to absolve pharmaceutical companies and doctors of all liability. There certainly have been dubious advertising campaigns and overprescriptions. There are still people dealing with addiction to prescription medications, and that problem was much worse in the previous decade. The error made today is underestimating the effectiveness of measures undertaken to control prescription drug abuse and the role of street drugs as a far deadlier problem today.

Even the street drug crisis keeps mutating, as USA Today noted in September that heroin use is declining among middle-aged addicts as they turn to methamphetamine and marijuana. Unfortunately, younger addicts are still hungry for heroin and often end up dining on deadly fentanyl served by their suppliers. The one positive change among 18-to-25-year-olds is a very substantial decline in the abuse of prescription opioids in 2017.

Caught in the political crossfire are chronic pain patients, who strongly object to being viewed as incipient drug addicts, and even more strongly object to the loss of vitally needed pain medication. These patients have taken to holding public rallies to draw attention to their plight. Unfortunately, they face the grim irony that some patients are in too much pain to attend rallies now that they cannot obtain the medications they need.

“The CDC has never seen my medical records, they have never examined me. They have no right to change my prescription. I have to be drug tested every month to prove that I’m not taking heroin, ecstasy and all these other drugs I’ve never even heard of,” complained Micki Forrester of Washington state at one such rally on Tuesday.

Forrester suffers from a debilitating nervous system disorder that leaves her in constant pain and occasionally confines her to a wheelchair. She said she can no longer travel because the new CDC guidelines require her to constantly renew her prescriptions every month, and she worries about being tagged as a doctor-shopping drug abuser if she tries to fill her prescription out of state.

“We are not criminals. We’re just in pain,” Forrester said. Unfortunately for chronic pain patients, they’re also politically invisible, and going after the actual criminals responsible for all this would be hard work with no political or financial payoff for the Beltway elite.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.