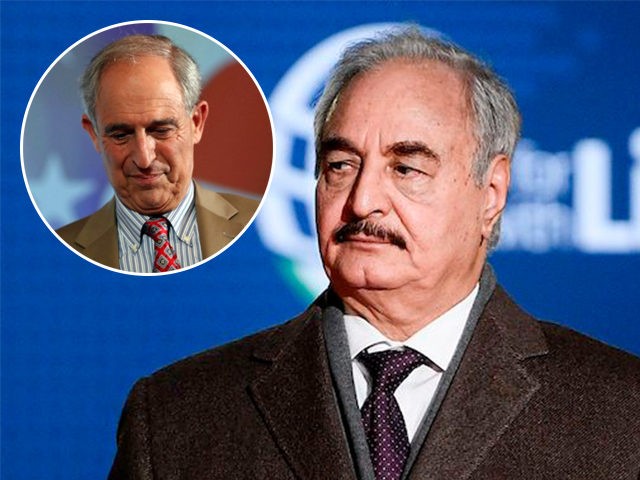

Libyan warlord Khalifa Haftar, who laid siege to the capital city of Tripoli for 14 months until Turkish military intervention pushed his forces back in June 2020, has hired former Bill Clinton senior aide Lanny Davis and former Republican congressman Bob Livingston of Louisiana as lobbyists. Haftar is apparently trying to exert some influence over the next Libyan election, or possibly run for the presidency himself.

The Wall Street Journal (WSJ) on Wednesday quoted papers filed with the U.S. Justice Department (DOJ) that indicated Davis and Livingston were hired to help Haftar secure meetings with the Biden White House, State Department, and Congress in advance of Libya’s December elections.

Davis and Livingston were more specifically hired to express “Field Marshal Khalifa Haftar’s support of free and fair, UN-supervised elections on December 24 – to facilitate a peaceful, stable, unified, democratic Libya, under the rule of law.”

Michael Cohen (L), US President Donald Trump’s former personal attorney, and his lawyer Lanny Davis arrive in the Hart Senate Office Building in Washington, DC, on February 26, 2019. (Mandel Ngan/AFP via Getty Images)

The WSJ suggested this might be a delicate task, as Haftar is currently being sued in U.S. courts for war crimes and human rights violations. Quizzed on the subject by the WSJ, Davis and Livingston responded that Haftar denies all of the charges. They insisted they would not have worked for him otherwise.

Then-Speaker of the House of Representatives Robert Livingston (R-LA), speaks to the media after a meeting of the House Republican leadership on the hearings on the impeachment of US President Bill Clinton, December 17, 1998. (Paul Richards/AFP via Getty Images)

Turkey’s Daily Sabah, which unflatteringly refers to Haftar as a “putschist,” said on Wednesday that Haftar unsuccessfully tried to have the U.S. lawsuits against him dismissed by claiming he should enjoy immunity as a head of state. The judge noted that both the Trump and Biden State Departments declined invitations to assert an interest in his case.

Haftar, 77, was one of the military leaders who helped Col. Moammar Qaddafi seize power in 1969. It was Qaddafi gave Haftar the title of “field marshal” that Davis and Livingston used when referring to their client, but the two later had a falling-out after Haftar failed to overthrow the government of Chad in the early 80s, the victorious Chadians took him prisoner, and Qaddafi hung him out to dry.

Haftar decided to overthrow Qaddafi while stewing in Chadian prison, but he wound up moving to the United States and living near CIA headquarters in Virginia for the next two decades. The “Arab Spring” uprisings of 2011 inspired him to return to Libya and take another shot at Qaddafi, who was overthrown and killed after President Barack Obama’s disastrous military intervention.

In the mad terrorist-drenched chaos of post-Obama Libya, Haftar gained a reputation as a ruthlessly effective fighter against jihadists. He named his war against them “Operation Dignity” and even made a point of targeting the jihadis who overran the U.S. consulate in Benghazi in 2012.

Haftar called his forces the “Libyan National Army” (LNA) and acted under the auspices of a rival government called the “House of Representatives” (HOR) based in Tobruk. The HOR claimed to be the legitimate government of Libya and enjoyed support from Russia, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Egypt, and France, the latter giving significant military support to Haftar while publicly endorsing the U.N.-backed Government of National Accord (GNA) in Tripoli.

Members of the “Saiqa” (Special Forces) of the self-proclaimed Libyan National Army cheer a Russian-made Libyan Mil Mi-8 helicopter flies during an event in tribute to the unit’s late commander General Wanis Bukhamada, who died a week prior, in the eastern city of Benghazi on November 6, 2020. (Photo by Abdullah Doma/AFP via Getty Images)

The argument over whether to support Haftar and his LNA over the GNA was complex and frequently bitter. Some of his international backers wished to counter Turkey’s growing influence in Libya; some thought he was more effective at neutralizing terrorists threats than the GNA; some thought Libya will never be stable unless Haftar and the HOR are incorporated into the national government somehow. Moscow couldn’t help noticing there was a great deal of oil bubbling under the ground controlled by the LNA.

Haftar and the LNA were not decisively defeated when Turkish forces helped to push them out of Tripoli. He lost a great deal of his foreign support, but he retains control over considerable territory in eastern Libya, and he has demonstrated the ability to choke off Libya’s oil exports. The LNA frequently complains about Turkish “mercenaries” operating on Libyan soil and says it will never stand down while foreign forces are present in the country.

The parliament in Tripoli on Thursday approved a plan for presidential elections on December 24, although another powerful government body, the High State Council, challenged the decision and said the law authorizing the elections was “flawed.”

Observers such as the European Council on Foreign Relations suspect the election plan will be scuttled by such bureaucratic infighting. The European Union (EU) on Thursday pledged to “give more” support to Libya’s High National Electoral Commission” and “help the Libyan government reform the security sector” so elections can be held.

The EU’s top diplomat, Josep Borrell, applauded “the many advances made over the past year” in Libya, including “ceasefire, unified political institutions, and [a] roadmap for elections,” but insisted holding those elections are vital to “consolidate this progress.”

If the election is held and Haftar runs, he will likely face Moammar Qaddafi’s son Saif al-Islam Qaddafi as a major opponent. Saif Qaddafi vanished from public view shortly before a court in Tripoli sentenced him to death in 2015 for human rights violations during the revolt against his father, but resurfaced in a July 2021 interview where he expressed a desire to run for office, along with confidence that his “legal issues could be negotiated away” if he won.

In this February 25, 2011 photo, Seif al-Islam Gadhafi, son of Libyan leader Moammar Gadhafi, speaks to the media at a press conference in a hotel in Tripoli, Libya. (AP Photo/Ben Curtis, File)

Libyan prosecutors swore out a fresh warrant for Qaddafi’s arrest in August, accusing him of illegal ties to the same Russian mercenary group that supported Haftar when he marched on Tripoli.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.