“Republic of Thirst” is a three-part series made possible by a generous fellowship from the Robert Novak Foundation. Part I of examined the debate over how California’s scarce water resources should be allocated. Part III will examine whether those resources can be expanded through technological innovations like desalination. Part II examines whether more can be done to store and manage the water that falls naturally on the Golden State.

***

The water burst out through the spillway in a constant gush, a mad torrent of white, unstoppable and ferocious. It swept down the smooth concrete — then pounded into the new cracks in the failed spillway, sending a spray hundreds of feet into the air and carving a new chasm in the hillside.

Alongside the ruined structure, new channels appeared in the earthen emergency overflow spillway, strewn with rip rack rock that had been dropped by helicopter to keep the hillside from collapsing, to save the cities downstream.

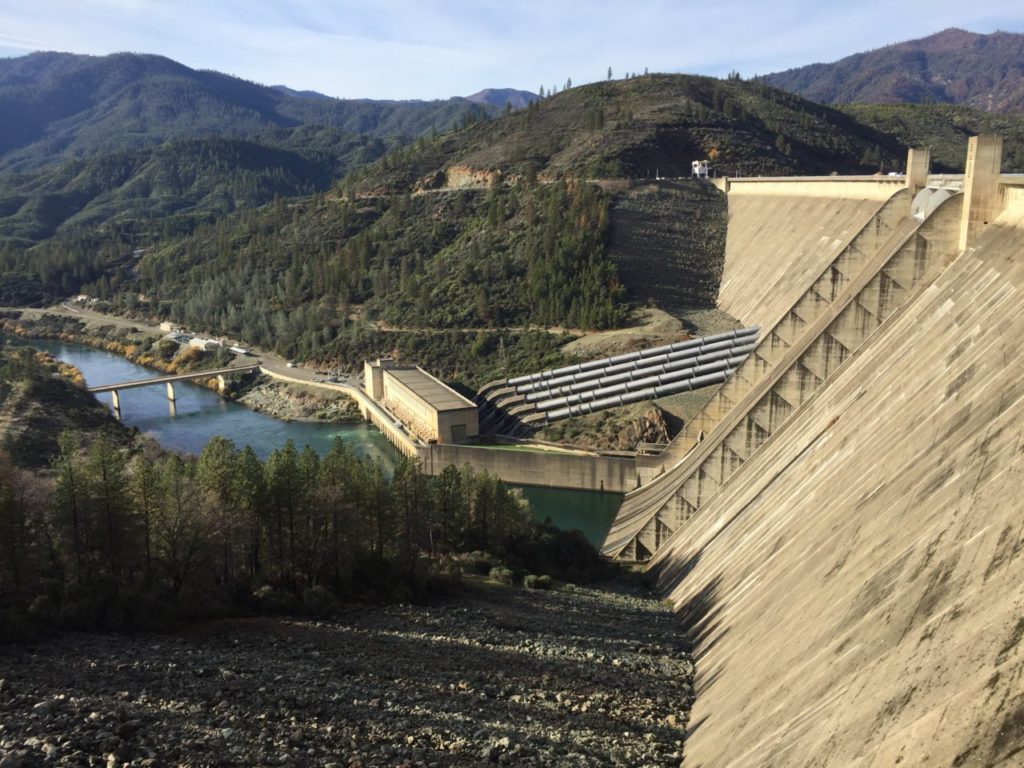

Viewed from a small airplane above the Oroville Dam — at 770 feet, the highest in the U.S. — in March 2017, the future of water storage in California looked doubtful. That year, California’s deep drought was broken by record rainfall, filling that dam and many others.

As water continued to pour in, authorities opened the spillway gates as wide as possible. But the concrete cracked, and the main spillway failed — spectacularly. The earthen emergency spillway, used for the first time ever, eroded itself and nearly failed.

Initially, local authorities evacuated nearly 200,000 people downstream of the dam. But a herculean effort by engineers managed to save and stabilize the emergency spillway, averting a massive disaster.

Still, the crisis provoked questions about whether state authorities had mismanaged Oroville Dam or ignored warnings about the structural integrity of the spillway — or even of the dam itself, which, some claimed, had already begin to leak.

To critics of dams, especially among environmentalists, the events at Oroville Dam were further proof of the dangers of dams and reservoirs — which, they argued, stored water only at great cost to nature and great risk to human life.

To others, especially advocates of industry and agriculture, the Oroville near-disaster was proof the state government had neglected California’s infrastructure needs in favor of redistribution, water conservation mandates, or flashy pet projects.

***

Life as we know it in California today would be unthinkable without the extensive system of dams, reservoirs, pumps and aqueducts that make urban life possible and that have transformed the drought-prone Central Valley into the most productive farming region on earth.

And yet it is a system that remains almost frozen in time, constructed largely during the early 20th century, the New Deal era, and the postwar boom that followed — designed for a population of 10 million, in a state now reaching 40 million.

It is also a system replete with ironies. The state that gave Ronald Reagan to America, and with him a new brand of unapologetic conservatism, is one in which the survival of the population depends on massive investments in infrastructure — albeit paid for, ultimately, by water users themselves.

Moreover, the liberal cities that have incubated America’s utopian environmental movement for decades could not exist without ongoing human intervention in the environment that brings water from mountaintop to tap.

For decades, policymakers have debated whether to build new reservoirs. One project, the Auburn Dam, was authorized by Congress in 1965 for flood control, but later abandoned over structural and environmental concerns. Numerous other proposals have been studied for decades, with little progress at the state or federal level — though local authorities have built their own projects, such as the Los Vaqueros Reservoir in the East San Francisco Bay, one of the few projects environmentalists have not opposed (though many have since opposed its expansion.)

Another project, the Sites Reservoir, has been debated for decades. Rather than capturing water by blocking a river with a dam, the reservoir would be built in a valley with minimal water and would receive excess water during floods, relieving pressure on other dams and allowing them to store more.

As Robert Dolezal of the California Water Alliance, a non-profit advocacy group funded by the state’s business community, told Breitbart News:

Sites Reservoir … reduces the flood potential of the Sacramento River … and it allows the entire Central Valley system, all the other major dams in the north — Trinity, Shasta, Oroville, and Folsom — to rebalance … [A]s much as 3 million more acre-feet of water can be stored in Trinity, Shasta, Oroville and Folsom because they don’t have to prevent flooding of Sacramento and other downriver communities, rebalancing the system. A similar proposal to raise the height of the Shasta Dam has a similar purpose, as would Temperance Flat on the San Joquin River near Fresno.

But critics say these dams would achieve little for storage, while hurting fish populations and destroying Native American heritage sites. They call such projects “vampire dams” — “because they so often rise from the dead” after being rejected by state leaders, one wrote recently.

The divisions over water storage do not match partisan divisions on other issues. In the Central Valley, Democrats tend to be as vociferous in their advocacy for water storage as Republicans are. And in the past, Republicans were as skeptical of such projects as urban Democrats are today.

Regardless of political predilection, during years of drought, one thought pervades public consciousness: how much water is left? Residents anxiously turn to the state’s reservoirs as they slowly drain, and dry.

The consequences of poor planning, and political infighting, have become clear — from a distance, at least for now. Across the ocean, the South African city of Cape Town, Africa’s most advanced and cosmopolitan city, provides a new warning. Its population has doubled over the past two decades, but it has not built much new water storage capacity — thanks, in part, to the fact that the national government has authority over water and the local government is controlled by the opposition. As a result, the city nearly ran out of water in 2018, forcing severe restrictions on residents.

That foreshadows California’s grim fate — if it cannot find solutions now.

***

“Droughts are nature’s fault. Water shortages are our fault.”

Rep. Tom McClintock (R-CA) greeted me in his office on a frigid Tuesday in December. He is one of the last seven Republicans left in the 53-strong California congressional delegation after Democrats won the midterm elections.

The hallway was strewn with the furniture of departing GOP colleagues, but for McClintock, it was business as usual. And the business at hand was water storage in California.

A continent away, frantic negotiations were continuing on the eve of the State Water Resources Control Board (SWRCB) decision on the Bay-Delta Plan, the controversial new policy that will mandate that rivers in the San Joaquin watershed must have an average of 40% “unimpeded flow” during the spring months — a decision that shifts precious water from farmers and cities to the environment in an effort to save threatened fish populations.

McClintock’s office was well-apprised of the state of talks between the various parties, including outgoing Governor Jerry Brown and incoming governor Gavin Newsom. The two liberal Democrats asked the SWRCB to postpone its decision, originally scheduled for November, to Dec. 12 to leave time for voluntary agreements with local water authorities. (The day following my meeting with McClintock, the SWRCB voted to approve the Bay-Delta Plan, despite some agreements being reached.)

The governors’ real priority, some skeptical observers claimed, was to secure enough water for the California Waterfix — the “Twin Tunnels” project that will divert water from the Sacramento River under the California Delta to be pumped south.

But that is a fight about allocation. McClintock focused on storage, noting that the cheapest and best way to solve the state’s water problems — measured in cost per acre-foot — is to build more reservoirs rather than letting much of the state’s rainfall run out to sea. McClintock reminded me that it has been 40 years since California’s last dam, the New Melones Dam, was completed in 1978.

The state’s largest water reservoir — by far — is the natural reservoir provided by its Cascades and Sierra Nevada Mountain Range snowpack. That dwarfs the man-made facilities and, through gradual snowmelt in spring, continuously refills the man-made reservoirs long after winter rains and snows have stopped for the season.

Though smaller than nature’s own reservoir, California’s system of man-made reservoirs is vast — and complex. The Public Policy Institute of California notes that “state and federal agencies manage 240 large reservoirs that account for 60% of the state’s storage capacity,” with the rest of the state’s reservoirs owned and operated by local water agencies, or by private entities for use on private lands.

The California Department of Water Resources notes: “On average, California receives about 200 million acre-feet of water per year in the form of rain and snow.” (It adds that the state rarely experiences an “average” year.) The state’s reservoirs can capture about 42 million acre-feet of that — roughly one-fifth. The rest seeps into underground aquifers, or flows out to the sea.

Dolezal notes that California uses an average of about 80 million acre-feet of water per year, and over the past two decades, roughly half of that is preserved for environmental use — dropping to 40% in the most recent drought, with agriculture using just over 40%, in both wet and dry years.

The reservoir system has a variety of purposes — and storage is just one of them. Many dams and reservoirs were built for flood control.

The state’s capital city of Sacramento, which sits at the confluence of the American and Sacramento Rivers, was inundated during the Great Flood of 1862, which “turned enormous regions of the state into inland seas for months,” Scientific American recalled. That event, and others like it, fueled enthusiasm for building dams.

California’s dams are also multipurpose facilities, providing hydroelectric power generation; water storage and supply; recreation; and flood management protection.

But tn times of drought, such as the unusually severe drought that gripped the state from 2011 to 2017, storage is the most salient priority. And McClintock believes there is too little of it.

He and others argue that California can add to its storage capacity relatively easily — not just by building new dams, but expanding existing ones, such as the Shasta Dam, one of the major reservoirs in the federal Central Valley Project, which supplies water to farmers hundreds of miles south.

Shasta Dam was built under President Franklin Delano Roosevelt during World War Two, reaching 602 feet, though it was designed to be even bigger. (An even bigger dam was envisioned for the Klamath River, but was canceled in the 1970s; today dams along the Klamath are set to be torn down.)

“Simply finishing the Shasta Dam to its design height [of 800 feet] could add nine million acre-feet to the system,” McClintock says. Indeed, the Trump administration, is proposing to raise the dam by 18.5 feet, increasing the capacity of the dam by 7 percent (630,000 acre-feet) — if tiny salamander species that environmentalists wish to have declared “endangered” do not stop plans for expansion.

Another proposal is to build the Sites Reservoir in the foothills west of the small town of Maxwell, just over an hour north of Sacramento. As noted earlier, the Sites Reservoir would store 500,000 acre-feet of “off-stream” water, meaning that it would not dam an active river, but rather be a site for water from other sites to be stored as available and used as needed. Proponents argue that it would contribute to environmental quality as well as the state’s storage capacity.

Crucially, the Sites Reservoir appears to have some startup funding. As much as half of the money will come from a special water bond passed by voters in Proposition 1 of 2014, which set aside $2.7 billion (of $7.5 billion) for water storage projects. The rest of the project would theoretically be funded by long-term contracts for water not reserved for public use.

Jim Watson, general manager of the Sites Project Authority, told Breitbart News that he was confident the project would proceed, given the support of the voters for water storage when they passed Proposition 1. He noted that $816 million had been set aside for Sites — the largest project funded by the proposition bond, compared to several competing projects. He added that local water agencies had also been working with state and federal authorities in preparing studies for the project.

“Some of the water that will be produced from the project will be dedicated for environmental projects,” he said, nothing that some water would help fish, and some would supply existing refuges that support waterfowl species.

Given that “no formal opposition” was raised by environmentalists during the approval process for Sites, he said, he did not anticipate significant opposition from them — though they were skeptical the reservoir would provide the water promised. Watson said the project was consulting with environmental interests to allay those concerns, and to explore their thoughts about how the water should be managed once it had been stored, in the reservoir. He said the management process the project had developed would include local communities and Native American groups. And he added that the Sites Reservoir will have “statewide reach” by helping recharge depleted aquifers throughout California — an urgent necessity once the state’s new groundwater management requirements go into effect in 2020.

“Three years ago, the concept of a local agency taking on such a project, that had been on the board since the 1950s, seemed pretty remote,” he said. “We have now become the state’s lead agency for complying with environmental requirements.

“We’ve come a long way … we’re starting to put the pieces together,” he added with evident pride.

Likewise, Erin Curtis of the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation told Breitbart News, “There is a lot of momentum for the project right now.

“And obviously,” she added, “for any project in California, especially related to water, there’s going to be some discussions with environmental organizations and local landowners, but it did get Proposition 1 funding.”

Curtis described the value of the project in terms environmentalists might understand: given that the state’s climate is changing, and becoming warmer, that means more of California’s annual precipitation is falling as rain, rather than snow.

Without that frozen, natural reservoir, the system must build new capacity to store water — or else it will be lost, not just to industry and agriculture, but to environmental and recreational users as well.

“We have been getting less and less water in the form of snowpack, which means less storage — we get more rain, so we can’t store it.” Sites, she said, provides “another place to put that water.”

Critics, however, say that state authorities allocated just enough money to the project to make it appear as if they are spending money on water storage, while not quite enough to allow the reservoir to be built.

McClintock is among the skeptics. He told Breitbart News that he has been hearing talk about the Sites Reservoir for decades, and that Californians are constantly told that construction is imminent. But somehow, that reservoir, and others, are never built.

He blamed the state and federal environmental laws and regulations that make dams more difficult, and more expensive, to build. “Until we change the environmental laws, construction is cost prohibitive,” he told me.

That would be perfectly fine with many environmental groups, for whom opposition to dams has become something of an article of faith over the past several decades. Dams were once thought to provide an environmentally-friendly source of renewable energy, through hydroelectric power. But they destroy whatever habitat finds itself submerged by reservoirs; impede fish migration; and — if managed poorly — create new hazards, such as mechanical failure.

McClintock dismissesdconcerns about Oroville. “No dam, no work of man is perfect,” he said. “We make mistakes, we learn, we go forward.”

That is, dam projects would go forward — if there were the political will to build them.

The lack of will has less to do with engineering challenges, he maintains, than it does with politics, bureaucracy, and lawsuits by radical environmentalist groups.

Environmentalists have made no secret of their opposition to the Sites Reservoir. The Sierra Club has cast the project as a fatal threat to the Sacramento River, declaring:

The Sites Reservoir would be filled by significant water diversions from the Sacramento River, which could harm the river’s dynamic flow-based ecosystems. More than 20,000 acres of federal and state public lands along the river that were acquired to protect and restore the river’s riparian and aquatic habitats, could be degraded by the diversions.

In addition to reducing flows in the Sacramento River, the reservoir would drown up to 15,000 acres of existing oak woodlands, grasslands, wetlands, and agricultural land in the western Sacramento Valley. Impacts associated with the reservoir footprint would harm the federally protected bald eagle, a host of other sensitive wildlife species, several rare plants, and significant historical and cultural resources.

The Sites Project Authority, a consortium of water districts and local governments, claim that the reservoir could store up to 1.8 million acre feet of water (making it the seventh largest reservoir in the state) and reliably yield about a half million acre feet of water annually for communities, farms, and the environment. But this yield estimate fails to adequately consider the effects of climate change, chronic drought, and reservoir evaporation on project storage and deliveries.

…

Sites supporters are essentially proposing to take water away from the environment, while promising to give back a small portion of that water for dubious environmental purposes.

The Sites project’s alleged “environmental benefits” seem little more than window dressing to secure public funding through the state water bond (Prop. 1) and to gain the support of gullible politicians.

Historian, essayist, and family farmer Victor Davis Hanson told Breitbart News that the environmentalist opposition to the Sites Reservoir is less about the actual impact of the project and more about hostility to commercial farming.

Once, he said, dams were favored by Democrats –part of the “1950s, 1960s, can-do attitude. And the people who opposed it were sort of Republican tight-fisted guys who didn’t really believe the government should be doing this.”

Now, however, “They don’t want agribusiness on the west side of the San Joaquin River. … They don’t believe in artificially changing the earth, or allowing a bunch of corporate farmers to make a killing.”

The Sites Reservoir, he noted, was originally one of several low-elevation reservoirs planned for the system, including Temperance Flats on the San Joaquin River. They were “integral to the original design,” he said, because they would allow flood waters to be captured during occasional years of heavy rainfall and snowmelt. They have the additional benefit of being low-cost and away from seismically sensitive regions that complicate construction.

What had particularly irritated environmentalists in recent years, he said, was that the farmers on the naturally dry west side of the valley had found ways to survive even when their federal water allocations had been slashed. They switched to highly profitable permanent crops like almonds, found water in a hitherto-unknown deep aquifer, and adopted high-tech solutions such as drip irrigation.

That, environmentalists said, proved that farmers could survive without more water storage. But it also meant that farmers were “systematically draining their aquifer” — a potential catastrophe.

And most farmers prefer surface water to water pumped from wells below: it is generally better for crops, and pumping water uses costly energy, Hanson noted.

“Environmentalists feel that if these things [reservoirs] fill up, no matter what they do, they can’t stop agriculture and agribusiness,” he concluded.

Hence the rough political road ahead, potentially, for the Sites Reservoir.

***

A week after meeting with McClintock, I traveled to the unincorporated community of Sites itself to examine the proposed future reservoir. The town, such as it is, sits at the end of a narrow, winding road at the end of the main street through the tiny rural town of Maxwell, just west of the Interstate 5 freeway. The road begins on a plain, then twists and turns through foothills along a small creek as cattle graze lazily in the tall grass along the steep banks.

At the end is a T-junction, a sign commemorates John Sites, the landowner for whom the area was named. A few homes and farms cluster near the junction, from which dirt roads branch out to the north and south. Beyond lies a shallow green valley, home to just over a dozen families, where herds of cattle graze placidly on non-irrigated land.

The whole north-south valley, roughly up to the area of the T-junction, is set to be inundated with water, eventually, under the plan prepared by the Sites Reservoir project.

It looks almost ideal for a reservoir — and many of the locals feel the same way. In 2015, the Santa Rosa Press Democrat interviewed fifth-generation cattle rancher Mary Wells, who said that while she was sad at the prospect that her family home could be underneath 350 feet of water, she recognized the urgent need the water could meet: “I wish it was here last year. Because I look at generation six and seven and say if I’m going to give them a legacy, we’ve got to have more [water] storage.” Other locals agreed: “It’s a bonanza of advantages where the disadvantages are few,” a Maxwell rancher told the paper.

The local Appeal-Democrat applauded the Trump administration for offering a $449 million loan to build a pipeline connecting two nearby canals, which will also serve the Sites Reservoir.

However, an editorial warned, the overall cost of the project was $5.1 billion, meaning that proponents would have to commit to “years of advocacy” before succeeding.

To that end, even lame-duck Republican congressman Jeff Dunham, who had just suffered a close defeat in the midterm elections, continued to promote the project. He told the local Manteca/Ripon Bulletin: “I made a promise to the voters and we are living up to that … Water is our future and I am always going to continue to work for that.”

The enthusiasm for the Sites Reservoir is bipartisan. Sen. Dianne Feinstein (D-CA), who often partners with Republicans on water issues, issued a statement reacting to the grant:

California must expand our water storage capacity so we can save more water from wet years for dry years. As we continue to experience the worsening effects of climate change, that need will only become greater in the future.

Projects like the Sites Reservoir are vitally important to counter climate change. Once completed, this 1.8 million acre-foot off-stream reservoir will allow us to catch excess Sacramento River flow, saving it for environmental, agricultural and residential use.

Former California State Assemblyman Dan Logue, a Republican who represented the area in which the Sites Reservoir is to be situated, co-authored a bill in 2014 with a Democratic colleague to fund a water bond to build it.

He told Breitbart News that he remains confident the reservoir will be built, given bipartisan support for the project, and given that it does not block an existing river. “If any one’s going to be built, this is going to be it,” he said.

But other proponents of the dam are less optimistic about the prospects for the Sites Reservoir — even if the dam is completed.

Former State Assembly Republican Caucus Chief Consultant Doug Haaland, an authority on water issues in the state, told Breitbart News that when Republican Governor Pete Wilson first signed the law authorizing the Sites Reservoir in 1994, “my grandson was nine months old. Now he’s twenty-four, and we haven’t turned a spade of dirt” at Sites.

Even with the Sites Reservoir in place, he said, he was skeptical about the overall impact on the state’s water supply. “The effect of Sites is going to be negated by the new water flow restrictions the state board is imposing” through the Bay-Delta Plan he said. “More [fresh] water flows out to sea under the Golden Gate Bridge every day than the reservoir can save.” The SWRCB seemed to have made its decision for the sake of the fish without a sense of the state’s overall water supply.

In addition, Haaland told Breitbart News, the state simply had not prioritized water. “We could have built Sites, Temperance Flat, and several others in between for all the money we are spending on high-speed rail,” he said.

When California began to grapple with climate change, he added, residents were warned about the strain on the state’s water supply — but then the state government neglected to do anything to add to California’s storage capacity.

Climate change had become an argument for more new projects, ostensibly to save energy and cut down on fossil fuels, rather than an impetus for holistic planning that examined the state’s needs and how it could use resources, including water, more efficiently. Planning for new water infrastructure like the Sites Reservoir had become an ad hoc process, shaped more by political opportunism and clout than any management principles, program, or plan.

Some of those involved in water planning in the state told Breitbart News that the Sites Reservoir had the advantage of being more organized than other projects — better prepared with maps and studies showing regulators a range of anticipated impacts, in anticipation of lengthy public consultations and debates.

Still, like many water plans, it is subject to the ebb and flow of public interest — intense during drought years, and nonchalant when rain is plentiful.

***

One such plan that has returned, repeatedly, throughout the history of California water policy is the idea of bringing water from the Sacramento River to the San Joaquin River valley, and from there to Southern California. The existing state water project follows that model somewhat, with the existing dams providing water to communities of the Central Valley, and water from the California Delta pumped south from the Jones plant near Tracy, California.

But planners have always envisioned a more ambitious plan — one that brought water directly from the Sacramento watershed south, bypassing the Delta. A century ago, in 1919, the U.S. Geological Survey’s Lt. Robert B. Marshall proposed the idea, but its prospects were dimmed by the Great Depression. It was Governor Jerry Brown, then in his first term, who convinced the state legislature to authorize the Peripheral Canal to accomplish that purpose.

Yet the Peripheral Canal ignited political tensions in the state, “pitting environmentalists and Northern Californians against farmers and Southern Californians, and destroying political careers in the process,” as the Los Angeles Times put it in 2007, after Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger revived the idea. Voters defeated the Peripheral Canal in a statewide referendum, Proposition 9, in 1982, but the natural and economic factors that inspired the plan remained.

After his return to the governor’s mansion, Brown proposed a new plan, the “Twin Tunnels” or California Waterfix — 35 miles long, 40 feet wide, and 150 feet deep. Opponents were not convinced: “He wanted the Peripheral Canal. The tunnels are the Peripheral Canal with a lid on it,” one said. Financial support for the project was also weaker than expected, as the cost grew, potential contractors for the water, withdrew, and the cost tripled to $17.1 billion.

Days before leaving office, Brown told journalists at the Sacramento Press Club that he was confident the tunnels would be built — even though his successor had been somewhat cooler to the idea. “The [California] Delta will be destroyed unless we have some kind of peripheral canal or a tunnel,” he said.

Brown also said he was confident his other pet project, the high-speed rail linking San Francisco to Los Angeles, would be built, despite enormous costs.

A few days later, I attended a public meeting of the Delta Stewardship Council, a government body charged with the task of ensuring compliance with the Delta Plan, the state’s effort to balance environmental values with other needs in the California Delta.

The December 20 meeting was to be a showdown over the California Waterfix, where opponents had prepared to argue the project violated the Delta plan.

And then, suddenly, on Dec. 9, the California Department of Water Resources withdrew its certification that the Waterfix met the Delta Plan’s requirements. The council still held its meeting, but it was rather anticlimactic.

The state is expected to re-submit its plans — but for now, Jerry Brown’s signature water infrastructure project is on hold.

With the fate of these massive projects still uncertain, and opposed by various interest groups from right to left, it might seem to make sense to focus on infrastructure projects that could make an immediate difference at lowest cost and least impact. The Sites Reservoir would seem to fit the bill: a guarantee of additional water storage during flood years that could provide additional reserves during drought years or recharge the state’s over-pumped aquifers.

The project seems to be creeping forward — slowly. But it is hostage to changing power dynamics in Washington and Sacramento; limited by the natural forces that cause projects like the Oroville Dam spillway to crumble; yet still driven by needs that require human ingenuity, in the face of natural scarcity, to be met.

Adding storage capacity remains the simplest and cheapest way to balance the needs of people and nature.

But in California, that has no bearing on the chances of whether it will happen.

Joel B. Pollak is Senior Editor-at-Large at Breitbart News. He is a winner of the 2018 Robert Novak Journalism Alumni Fellowship. He is also the co-author of How Trump Won: The Inside Story of a Revolution, which is available from Regnery. Follow him on Twitter at @joelpollak.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.