The elephant zebra in the room, actually stampeding through Roger Goodell’s office, today is the inconvenient truth that the NFL chose to disbelieve its own referee in the Wells Report. Worse still, the NFL repeatedly chose to disbelieve its own referee on the most crucial matter pertaining to Deflategate after repeatedly accepting his memory without question elsewhere in the report.

Walt Anderson told NFL investigators that his “best recollection is that he used the Logo Gauge” attached to a long, bended needle and featuring an “On” button before the AFC Championship Game. Because this gauge regularly registered readings .3-to-.45 higher than the other gauge (at least according to Wells), using it as the baseline for subsequent measurements puts eight of 11 Patriots balls tested by officials at halftime within or above the range where Wells’ scientific consultants told him the balls would deflate to because of weather conditions. Put another way, believing Walt Anderson means believing Tom Brady.

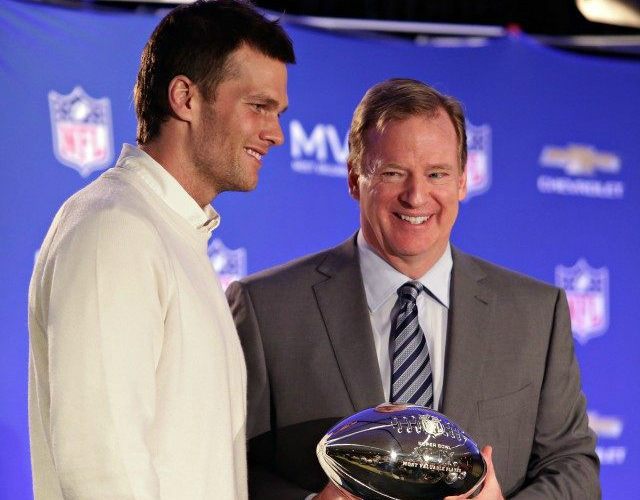

No one mistakes Walt Anderson for Gisele Bundchen or one of those Patriots fanatics, equally as attracted to the Super Bowl MVP, arrested at NFL headquarters in Manhattan. He’s a referee—not a back judge or a linesman or an umpire but an NFL crew chief—entering his twentieth season in the league. He’s the guy whose impartiality and judgment the NFL trusts so much that it made him not only a referee, but the referee for one of its conference championship games. Yet, the Wells Report simply accepts the opposite of his testimony as truth on the most crucial evidentiary aspect of Deflategate.

By this legal reasoning—citing the very opposite of what a witness testifies to as a keystone fact—one can prove anything. How could the world’s most successful sports league attach its name to something so bush league?

Elsewhere in the report Ted Wells tells readers to believe Walt Anderson’s memory because, well, just because.

“We credit Anderson’s recollection of the pre-game measurements taken on the day of the AFC Championship Game based on both the level of confidence Anderson expressed in his recollection and the consistency of his recollection with information provided by each of the Patriots and Colts regarding their target inflation levels,” Wells maintains—but just on the readings and not the gauge providing the reading, mind you. So, Wells assumes a 12.5 pregame psi measurement for every Patriots ball and a 13.0 pregame psi measurement for every Colts ball despite no documentation.

But even this fails. “Anderson recalls that most of the Patriots footballs measured 12.5 psi, though there may have been one or two that measured 12.6 psi,” the Wells Report admits, adding that, “According to Anderson, when tested, most of the Colts footballs measured 13.0 or 13.1 psi. Anderson believes that there may have been one or two footballs that registered 12.8 or 12.9 psi.”

In other words, nobody knows precisely the pregame pressure levels of specific balls even if we possess a ballpark sense for all the balls. Despite Anderson indicating variation, Wells imposes a one-size-fits-all measurement on each team’s balls. Who, really, believes that every Patriots ball measured at precisely 12.5 and every Colts ball measured at precisely 13.0 before the game? Not even the man who gauged the balls maintains that. Only Ted Wells does—except when he doesn’t.

Wells further convolutes this convoluted theory by explaining away the halftime variations in ball-pressure measurements—a range of .80 between just four Colts balls measured—by offering the belief of his scientific team that, actually, the ball measurements probably varied considerably before the game, too. Wells, citing an “unidentified and unexamined factor,” noted his scientists’ belief that “the most plausible explanation for the variability of the Patriots halftime measurements is that the eleven footballs measured by the officials at halftime did not all start the game at or near the same pressure, even though they all measured at or near 12.5 psi when inspected by the referee prior to the game.”

A team employee illegally manipulating the balls might explain this if the Patriots balls alone exhibited variation. But a huge pressure gap exists among the Colts balls on one official’s halftime readings that did not exist on the referee’s pregame measurements. Wells attempts to explain this away by theorizing, without any actual evidence supporting this, that the two officials who measured balls at halftime switched gauges. One possibility both Wells and his scientists discount, based on testing the two gauges, is a defect with the devices or their batteries.

Offering this as a possibility, like accepting Walt Anderson’s recollection on what gauge he used before the game, would undermine the incoming thesis that a New England Patriots employee manipulated the pressure of 12 balls during 100 seconds in a bathroom despite a room of referees testing the pressure of just four Colts balls (“running out of time,” says Wells) during an extended 13.5 minute halftime. So, rather than present the mere facts Wells imposes spin—that Walt Anderson used a different gauge than he said he did, that two other officials traded gauges at halftime, and that each team’s pregame ball pressure came in at uniform levels (except, of course, when he switches his story on this).

Any number of suppositions made in the Wells Report appear difficult, and in certain cases, impossible to believe. The commissioner commissioning Ted Wells to conduct the investigation believing it surely does not seem impossible to believe.

Tom Brady has triumphed against worse odds before. And certainly for players finding themselves in the commissioner’s office, the odds aren’t good. But then again the “goods” here against Tom Brady appear terribly odd.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.