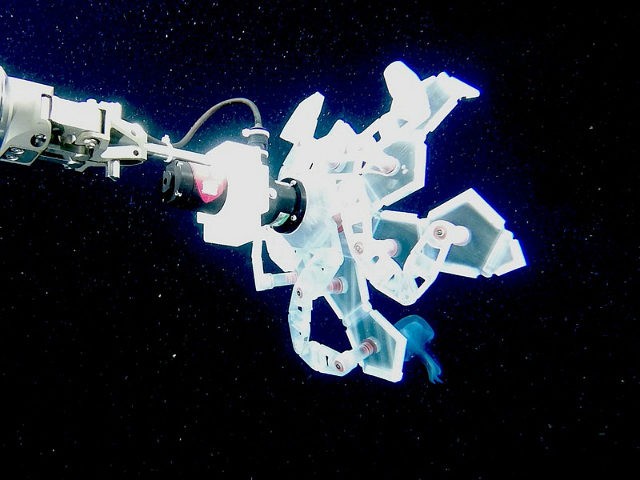

The rotary actuated dodecahedron, or RAD, gently embraces the world’s most fragile marine bodies.

Marine biologist David Gruber and his associates took inspiration from the ancient Japanese art of paper folding to create the RAD’s unique design. The device looks like high-tech origami and can be attached to the arm of a submersible vehicle for the safe capture of creatures like jellyfish, anemones, and sea cucumbers.

RAD is rated for depths as low as nearly seven miles beneath the ocean’s surface and has already been tested at over 2,000 feet down. Its creators say that it can also easily be enlarged for the capture of larger, soft-bodied sea life. These are important advancements for the study of the “forgotten fauna,” according to Gruber.

“Globally, gelatinous zooplankton are estimated to constitute a biomass of more than 38 billion kilograms of carbon,” he said. For reference, that is more than 100 times the collective biomass of the human race. Nevertheless, our inability to safely extract these creatures from their native environment has left them scientifically “neglected,” Gruber said.

The design challenges were numerous. The trap had to have enough open spaces for water pressure not to build and crush the specimens, but not so much that they could slip out. It had to be able to open and close with a single motor and combine durability with softness that would keep it from amputating the limbs of any animals who attempted to escape its confines.

Harvard University mechanical engineer Zhi Ern Teoh believes that the technology behind the device is impressively scalable and could even be used for self-erecting habitats in space. And while the current RAD is human-controlled, it is not much of a leap to design an automated version that could be left in the ocean until the right creature happens by.

Gruber, however, is not stopping there. “I view this as a platform technology that we hope will continue to evolve,” he told The Verge. “The dream is to enclose delicate deep-sea animals, take 3D imagery that includes properties like hardness, 3D-print that animal at the surface, and also have a ‘toothbrush’ tickle the organism to obtain its full genome. Then, we’d release it.”

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.