In the course of making my film The Bloody Road to Cleveland about the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement, I have been teargassed in Seattle, assaulted in Denver, kicked out of the Board of Supervisors meeting in San Francisco, and, as Breitbart News reported this weekend, arrested in Baton Rouge. This is my story of that arrest.

When I cover protests, especially shooting footage for this film, I don’t do it from a distance. I want to be where the action is, but I always balance this with obeying place orders. As anyone who follows my work here on Breitbart News is aware, I have been a tireless critic of the Black Lives Matter, and I’m also a strong supporter of law enforcement.

Covering Saturday night’s protests in Baton Rouge was no exception. Since protests started Tuesday night after the police shooting of a 37-year-old black man named Alton Sterling, the situation has escalated as angry black residents of Baton Rouge have taken to the streets. Initially, the protests were near the site of the shooting in a black neighborhood of north Baton Rouge, and Louisiana’s governor ordered the police to stand down.

By Thursday night, the protests had moved closer to white neighborhoods in the area of the Baton Rouge Police Department headquarters, and, perhaps as a response to Thursday night’s murder of five police officers in Dallas by a black liberation activist upset by, among other things, the Sterling shooting, the police were out in full riot gear and armed with heavy weaponry.

Meanwhile, Baton Rouge’s black Democrat mayor Kip Holden was nowhere to be found and was quoted as saying,“Why should I put my hand in a hornet’s nest?”

Without any leadership, whoever was giving the orders to the police was issuing a series of confusing and conflicting rules of engagement for dealing with protesters, and the result was an increasingly chaotic situation with no open lines of communication between police and protesters.

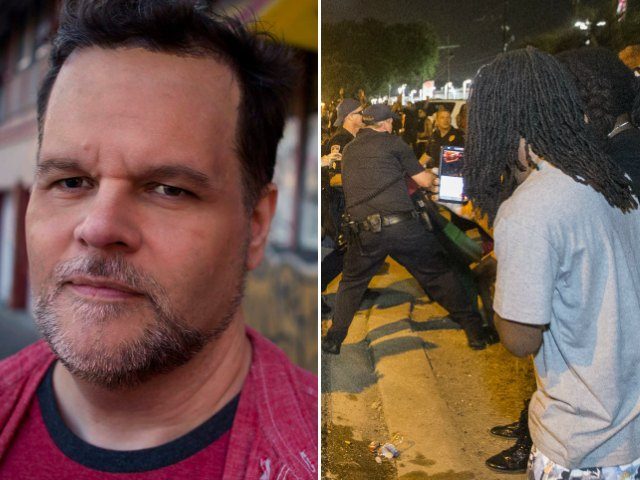

A little before midnight on Saturday, I was covering the protests near the Baton Rouge Police Department with a line of about 30 police officers onto Airline Drive. The road was shut down, and police were standing about 15 feet away from a line of yelling protesters on the side of the road. Suddenly, the police charged and began arresting people in the line.

I moved over to see what was going on, and while remaining at the front of the line of protesters, I moved laterally closer to the action. I shot a short video clip, which you can see shows that the road is closed, the police are in the road, and I was right next to both protesters and other photographers.

This is the clip I was arrested for filming. Saturday night #AltonSterlingProtest pic.twitter.com/zHHsFUSaLC

— ⏳ (@stranahan) July 11, 2016

After I shot this clip, I began to shoot again, when I was approached by two police officers, one of whom grabbed my camera, put my arms behind my back, and put on wire-tie handcuffs.

The last thing I saw before the cuffs went on. pic.twitter.com/hdFLHkUE7R

— ⏳ (@stranahan) July 11, 2016

I did nothing to break the law. I was not obstructing traffic because with the road closed and police blocking the lane, there was no traffic. At no point did I hear the police give any order for me or anyone else to stay back. I was given no warning whatsoever; I was simply approached and forced to stop recording.

As the video shows, the police came directly at me. I do not know why I was targeted. Other people shooting photos and video who were in the same spot that I was were not. I don’t believe race is a factor, since some of those other photographers were also white. I simply do not know.

The police took my camera and put a temporary pair of handcuffs on me. I was taken across the street and into the Baton Rouge Police Department headquarters for initial processing. There were about 15 other protesters being brought into the system at the same time; arrests were going on throughout the night.

It turned out that I was one of three reporters arrested that night, and it seems to me that reporters were very clearly targeted. I believe that officials in Baton Rouge would simply like this whole thing to go away and naïvely thought that stopping the messenger would help.

Every single person in the police department that I dealt with personally during my arrest and detainment was courteous and professional. Part of this may have been due to my attitude; I simply went along with the process. One reason I have this attitude is that I’m aware that the police are simply doing their jobs. The problems I experienced come from a higher level– the politicians who set policy.

Even though I did not agree with my arrest, I did not argue the point or act disrespectfully. I believe not being openly confrontational with law enforcement made my experience with them better.

On the other night, I saw a number of other people who had been taken into custody deal with the police in a way that was confrontational and rude. I got to see what law enforcement has to deal with on a daily basis.

While some of the protesters who had been arrested were acting disrespectfully, most were not.

During this initial phase, while the police got my information and took my property, such as my phone and wallet, I noticed a 16-year-old girl whom I recognized being processed close to me. The night before, I had spoken to her and her father; they had both seemed soft-spoken and intelligent but committed to exposing what they saw as injustice in the legal system here in Baton Rouge.

As I was put into metal handcuffs and led from this processing area, I saw someone whom I thought was familiar to me. I called out, “DeRay.” Sure enough, it was well-known Black Lives Matter activist DeRay Mckesson. He was at the end of the line of people waiting to be processed, even though he had been arrested an hour earlier than I had.

From the Baton Rouge Police Department, I was put into a van with 12 other people and brought to a location downtown. Here we were put in a jail cell where we waited while more processing was done. I was told that when I got to the Parish Prison I would be given an opportunity to make a phone call.

After an hour or two in this jail facility, I was handcuffed again and transferred with 11 others to the East Baton Rouge Parish Prison. Here, we were put into a 20’x20′ cell, and gradually, the number of protesters in that cell grew to about 30. At no point had I been told that I was arrested, what I was being detained for specifically, or my rights.

I was the only reporter in my group. The protesters were all black, except for one, a good-natured leftist named Sean, who had come from New Orleans for solidarity. His shirt was ripped, his knee bloodied, and his face bruised from his run-in with the police, where he said he’d been tackled in the grass. Despite this, Sean was in a relatively good mood and was the only protester in the group there who had any previous protesting experience.

Also in that group with me was Eddie, the 50-year-old man I had spoken to the night before with his 16-year-old daughter. I told Eddie that I had seen his daughter in processing earlier and that she seemed okay.

Another member of the group was Johnny, who seemed to know everyone who worked in the prison, and whom they knew, too. Johnny was a former drug dealer who had had a number of run-ins with the law, but he’s a natural born comedian, and the guards clearly enjoyed their banter with him, and there was a lot of laughter.

Johnny’s prior experience also helped because he became a resource of information about the process that I knew nothing about. He had given up crime a few years ago, he said, and gone into filmmaking, and he and I also discussed things like Final Cut Pro in between making jokes about the situation we found ourselves in.

While a number of the protesters I was in with would likely have no problem with being described as “young thugs” – in fact, they would probably take it as a badge of honor – that is definitely not the way the entire group should be described. There were also idealistic young people, a PhD who worked at LSU doing research on the connection between AIDS and alcoholism, a man who had his own web development company, and others who do not fit the preconceived stereotype some people may have of the type of people who would be arrested at a protest.

We had a lot of time to kill, and I had some great conversations. I quickly learned that the issue here in Baton Rouge for these people was not ideologically driven. Over and over, they told me the issue was not about Democrat or Republican but about the way law enforcement handles things in both Baton Rouge and the state of Louisiana in general, which has one of the largest incarceration rates in Western civilization. These protesters did not have the agenda of overthrowing capitalism that many of the top leaders of Black Lives Matter have; they want police abuse to end, and they see the Alton Sterling case as emblematic of that problem.

I was open with everyone about what I did for a living and that I work for a conservative website, as well as being a Republican. I encountered no hostility whatsoever for those beliefs, although I did get some genuine curiosity, particularly from some of the younger black man who had never really had a conversation with a Republican. They were curious as to my opinion of Donald Trump, and one of my fellow inmates told me flatly that he was planning to vote for Donald Trump. No one I spoke with seemed enthusiastic about Hillary Clinton.

After the first couple of hours, Sean, the white leftist from New Orleans, was able to get the number of the National Lawyers Guild in Baton Rouge. I have been a major critic of the NLG, the Institutional Left group that was founded by communist attorneys and that has protected people and groups that I find repugnant.

That being said: in this case, thank God for the National Lawyers Guild.

Sean gave me the group’s number, and I decided to call them and update them on the situation in the cell. At that time we had been given no information at all by the authorities and had no idea what was going on in the outside world.

I called the NLG number, and they were all set up to take a call from jail, where you have to call collect or on a calling card. I spoke to the person who answered at 2 a.m., and I told him who I was and that I was a reporter for Breitbart News. I gave him an update on what I know.

They told me that they had a team of about 20 lawyers currently working to get everyone freed and that they were planning to provide bond for everybody. They said that they had found out most people were being charged with obstructing a roadway and that the bond should be about $250.

I asked the other inmates for their attention for a moment, then explained to them who the National Lawyers Guild was and what was going on. Everyone was very appreciative just to have information and to know that people were actually out there aware of what was going on and working on the case.

Do I wish there was a conservative, pro-liberty legal group out there that I could’ve called? You’re darn right I do, but there was no such group involved in what was going on in Baton Rouge.

I’ll also mention that when my friend and colleague Brandon Darby went to pay my $250 bond hours later, he found out that the NLG had already paid it. Had simply paid everybody’s bond. Breitbart News will be sending the National Lawyers Guild a check for $250 to reimburse them, but I appreciate the gesture and consistency, covering my bond, even though they knew I was a harsh critic of theirs.

This dialogue with the Lawyers Guild continued over the next several hours, as they took the names and contact information of everyone who has been arrested and continue to update us with information.

By the time the sun rose, I had still not been able to speak to my wife, who was sound asleep with our children back in Dallas. Eventually, I got through to her, and she immediately sprang into action and contacted my friend Ali Akbar, who lives in Baton Rouge. From there, Ali contacted Brandon Darby and the rest of the Breitbart News team.

Once again, I want to say that I am grateful beyond words to the entire team at Breitbart News, and I thank both executive chairman Stephen K. Bannon and CEO Larry Solov for not just having my back, but reaching out to my wife, Lauren, several times and making sure she was okay.

Meanwhile, back in prison, we were all put into orange jumpsuits and given a towel, a bar of soap, toothpaste, and a pamphlet about the rules and regulations. Unfortunately, I didn’t have my reading glasses, as they had been taken into property during processing, so I was unable to read the rules and regulations.

Sometime around midmorning, more prisoners were brought into our cell temporarily, including DeRay. The cell was extremely crowded at this point, but when I noticed DeRay was there, I walked over and introduced myself, and we briefly spoke. I updated him about what I knew was going on from my conversations with my wife and the National Lawyers Guild.

Some people have said that they would have liked to have been a fly on the wall during that conversation, and I’m sorry to disappoint, but there really wasn’t anything substantive about it. He was moved to another cell after a short time.

At about noon, based on the conversations I’d had, I thought we were due to be released at any minute, but the authorities had other plans. I believe things were happening to slow down the process of release.

For the next eight hours or so, we were moved to a variety of rooms in the prison for short bits of processing, but endless amounts of waiting time. During this period, we had no access to phones and, therefore, no access to information from the outside world about what was happening.

First, we were marched past the fencing and razor wire into a room to watch an orientation film about prison rape, which included helpful suggestions like not to take a Snickers bar if someone offers it to you because you may be required to provide sexual favors in exchange. Full disclosure: nobody ever offered me a Snickers bar.

After the prison rape video, we were sent for another processing session. The deputy asked me my name and where I was from. I mentioned I was from Dallas, and he asked if I came there specifically to protest. When I mentioned that I was a Breitbart News investigative journalist, he visibly relaxed and said, “Really?” Turns out he was a big fan of both the site and Andrew Breitbart. However, that had no effect whatsoever on the way I was treated, which was no better or worse than any other polite prisoner.

From there, we went to the commissary. Earlier in the cells, we had been offered breakfast, but I chose not to eat at either the commissary or at breakfast. I had made a decision that even though I had been arrested and was being held, I was not going to participate in being a prisoner mentally, and I knew I would be out eventually and would have a meal of my own choosing.

I am diabetic, and I obviously had no access to either my pills or insulin. At about four in the afternoon, we all were taken to another room, where we had medical interviews. Because it was Sunday, they said they had no access to medication, which was locked up. Thank goodness people don’t need medication on Sunday, I thought to myself. I was given a blood sugar test later by the prison medical staff, but because I had not eaten, my number was not that high.

After hours in the waiting room outside the medical facility, we were all then moved to another part of the prison and put into areas with other people who were already incarcerated and convicted of crimes.

I was moved into J to, which is called a “classification line” of cells with bunks, phones, and a television set. This is the first chance in hours I had to get on the phone again with my wife, so I immediately called her and was told that my bond had been paid hours earlier and that Brandon had driven in from Houston, Texas, and was with Ali. Once again, I appreciate my friend and family’s support more than I can say.

On the line, I met some of my temporary cellmates, including a man who’d been convicted of second-degree murder for stabbing his wife in the neck after a domestic disturbance and another young man who told me he had been brought in on seven felony charges and was facing a bond of $300,000.

This was the situation I found myself in for filming a demonstration and facing a charge that was so minor that the bond was $250. This was also the same charges other protesters were facing, who were also going through a similarly drawn-out process that seemed designed to intimidate people, not deliver proper justice.

It seems to me that the entire process could’ve been done quicker, more efficiently, and at less expense to taxpayers, but – and this is obviously conjecture – at some point, authorities made a decision to make the entire process laborious for people.

After a couple of hours on the line, a guard came down and called my name. I knew I was in the homestretch and would soon be free. This final process took another hour-and-a-half or so. I was fingerprinted, changed back into my clothes, and got my property back.

As I walked through the prison gates and back to my freedom, a number of people were waiting across the way for friends and relatives. I had been told to look for people from the National Lawyers Guild to check in and let them know I was out, and I did so, expressing my gratitude to them personally for their work in this case. Soon, I was met by my friends and was off to have a dinner of gumbo and étouffée.

So is there a moral to the story?

When some people heard I’d been locked up with protesters, they expressed concerns for my safety based on the idea that being a conservative writer with Breitbart might put me at risk.

I never felt in danger one time, nor was I threatened in any way. I made it very clear to everyone I met who I was, what I did for living, and what I believed.

I tried to put my faith in Jesus Christ into action as best I could and tried to help everyone I came into contact with, whether it was a guard trying to do his job organizing all the prisoners, a fellow inmate who was worried about whether he could pay his bond, a National Lawyers Guild lawyer trying to keep track of who was arrested, or the police officer whose job it was to handcuff me.

I treated every person I met—protestors and police—with respect and humanity. I didn’t make anyone “earn” this basic level of respect or approach them with a chip on my shoulder. I looked people in the eye, and I listened.

When I see police and protesters clashing in the streets, I don’t see the problems that they both face being solved. A new approach is clearly needed, one that combines active listening and basic respect with an uncompromising commitment to the truth—not just in words, but in action.

Here, I talk about the arrest on SiriusXM’s Breitbart New Daily:

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.