More children from the fit; less from the unfit—that is the chief issue of birth control.1

–Margaret Sanger, Birth Control Review

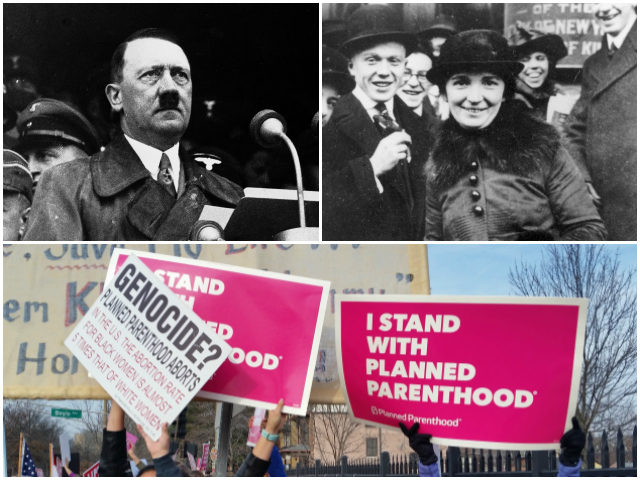

Margaret Sanger, the founder of Planned Parenthood, has an ignoble legacy as a racist who addressed the Ku Klux Klan and initiated a Negro Project to reduce the population of poor, uneducated African Americans whom she considered unfit to reproduce themselves. This Margaret Sanger—the real Margaret Sanger—is completely whitewashed in Parenthood propaganda, which deceitfully portrays Sanger as a champion of reproductive “choice.”

Even more incriminating than Sanger’s racism, however, is her close association with Nazism. Sanger was part of a community of American progressives who championed two remedies to get rid of “unfit” populations. The first was forced sterilization, which was Sanger’s preferred solution.

Sanger wanted to make it look like the sterilizations were voluntary. In a 1932 article, Sanger called for women to be segregated from the larger community onto “farms and homesteads” where they would be “taught to work under competent instructors” and prevented from reproducing “for the period of their entire lives.” If the women didn’t want to live this way, they could get out of it by consenting to be sterilized.2

The other progressive solution was “euthanasia,” which basically involved killing off the sick, the aged, and the physically and mentally disabled. One of Sanger’s colleagues, the California progressive Paul Popenoe, called for “lethal chambers” so that large numbers of “unfit” people could be systematically lined up and killed.3

The Nazis learned about these American programs, and enthusiastically adopted them. As Edwin Black documents in his book The War Against the Weak, the Nazi sterilization law of 1933 and the subsequent Nazi euthanasia laws were both based on blueprints drawn up by Sanger, Popenoe and other American progressives.4

In fact, the “lethal chambers” the Nazis employed using carbon monoxide gas to kill off “imbeciles” and other undesirables were the first death camps. Later these very facilities were expanded into Hitler’s “final solution” for the Jews, using many of the same medical personnel who manned the euthanasia killing facilities.

Sanger’s close associates Clarence Gamble, who funded Sanger and spoke at her conferences, and Lothrop Stoddard, who published in Sanger’s magazine and served on the board of her American Birth Control League, both knew about the Nazi sterilization and euthanasia programs and praised them. Stoddard traveled to Germany where he met with top Nazi officials and even secured an audience with Hitler. His 1940 book Into the Darkness is a paean to Hitler and Nazi eugenics.5

Sanger too was on board. In 1933, Sanger’s magazine Birth Control Review published an article on “Eugenic Sterilization” by Ernst Rudin, chief architect of the Nazi sterilization program and mentor of Josef Mengele, the notorious Nazi doctor at Auschwitz. Sanger’s magazine also reprinted a pamphlet that Rudin had prepared for British eugenicists.

Writing in 1938, when the Nazi program was in full swing, Sanger urged America to follow Hitler’s example. Using the language of Social Darwinism—the same language that Hitler uses in Mein Kampf—Sanger wrote, “In animal industry, the poor stock is not allowed to breed. In gardens, the weeds are kept down.” America, Sanger concluded, must learn from the Nazis and carry out nature’s own mandate of getting rid of “human weeds.”6

Hitler never quotes Margaret Sanger, but he was inspired by the writings of two of her associates, Leon Whitney of the American Eugenics Society and Madison Grant of the New York Zoological Society. During the 1930s, Whitney on one occasion visited Grant to proudly show him a letter he had just received from Hitler requesting a copy of Whitney’s book The Case for Sterilization.

Not to be outdone, Grant pulled out his own letter from Hitler, which praised Grant for writing The Passing of the Great Race, a book Hitler called his eugenic “Bible.”7 This incident shows how progressive eugenicists in America were well aware of their impact on Hitler and proud of their association with him.

Another example of progressive enthusiasm for Hitler involves Charles Goethe, founder of the Eugenics Society of Northern California, who upon returning from a 1934 fact-finding trip to Germany, wrote a congratulatory letter to his fellow progressive Eugene Gosney, head of the San Diego-based Human Betterment Foundation.

“You will be interested to know,” Goethe’s letter said, “that work has played a powerful part in shaping the opinions of the group of intellectuals who are behind Hitler in this epoch-making program. Everywhere I sensed that their opinions have been tremendously stimulated by American thought, and particularly by the work of the Human Betterment Foundation. I want you, my dear friend, to carry this thought with you for the rest of your life.”8

If Planned Parenthood and the Left today want to get away from this sordid history, they must stop denying it. Rather, they should repudiate and distance themselves from Sanger and her fellow progressives, who were not only racial bigots but also inspired some of the worst atrocities of the twentieth century.

Dinesh D’Souza’s new book The Big Lie: Exposing the Nazi Roots of the American Left is published by Regnery.

Citations

1 Cited by Richard Weikart, From Darwin to Hitler (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004), 135.

2 Margaret Sanger, “My Way to Peace,” January 17, 1932, Margaret Sanger Papers, nyu.edu/projects/sanger.

3 Paul Popenoe and Roswell Hill, Applied Eugenics (New York: Macmillan, 1918), 180.

4 Edwin Black, The War Against the Weak (Washington, D.C.: Dialog Press, 2013), xvii, 258.

5 Ernst Rudin, “Eugenic Sterilization, an Urgent Need,” Birth Control Review, April 1933.

6 Margaret Sanger, “Human Conservation and Birth Control,” March 3, 1938 speech, Margaret Sanger Papers, nyu.edu/projects/sanger.

7 Cited by Black, The War Against the Weak, 270.

8 Cited by Stefan Kuhl, The Nazi Connection (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994), 36, 46.

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.