Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny, who reportedly died under murky circumstances in a brutal prison camp at the age of 47 on Friday, was a fierce critic of strongman Vladimir Putin and the corruption of the Russian elite.

Navalny was himself imprisoned on corruption charges he dismissed as false and supposedly died while taking a walk after surviving an attempt by the Putin regime to assassinate him with chemical weapons.

Alexei Anatolievich Navalny was the son of a Soviet military officer and an economist who spent much of his youth living in his father’s military garrison posts. He often visited his grandmother in Chernobyl and the government coverup of the horrific nuclear disaster there in 1986 seems to have been a formative experience for him.

Navalny grew up to become a lawyer, obtaining his degree from the People’s Friendship University in Moscow in 1998. He earned an economics degree three years later and, while studying for that degree, he joined a pro-democracy, pro-market political party called Yabloko. He was expelled from Yabloko in 2007, supposedly because he engaged in prohibited “nationalist activities,” but Navalny said it was a power play by a rival for party influence.

Putin Critic, Russian Opposition Leader Alexi Navalny Dies in Arctic Penal Colony Says Russia https://t.co/OTrJFtN5rI

— Breitbart London (@BreitbartLondon) February 16, 2024

Navalny did take a more stridently nationalist tone during his early political career. Among other positions, he called for deporting migrants from Russia to preserve its ethnic integrity, he supported the Russian invasion of Georgia in 2008, and his criticism of Putin’s annexation of Crimea was rather nuanced.

Navalny said in 2014 that he disapproved of annexing Crimea, but a post-Putin government could not simply give it back to the Ukrainians, a position that did not endear him to the Ukrainians. He softened some of his nationalist positions in later years, or at least stopped taking about them, but they seemed to make it difficult for him to build a broader political alliance.

Navalny’s exit from Yabloko was the first of many times he would claim to be accused of wrongdoing for political reasons. Such accusations came with increasing frequency as he reported on the corruption of the Russian elite and became a persistent critic of Vladimir Putin, who rose to power in 2000.

Navalny won some major victories over the past two decades. During a brief interregnum in Putin’s power when Dmitry Medvedev was president of Russia, Navalny’s persistent criticism forced Medvedev to admit corrupt officials were embezzling over $30 billion a year from the national treasury.

Putin was back in the saddle soon enough, rewriting the Russian constitution to effectively make himself president-for-life. Navalny founded an anti-corruption website that pulled a million visitors a month. He dubbed Putin’s United Russia the “party of crooks and thieves,” and it stuck.

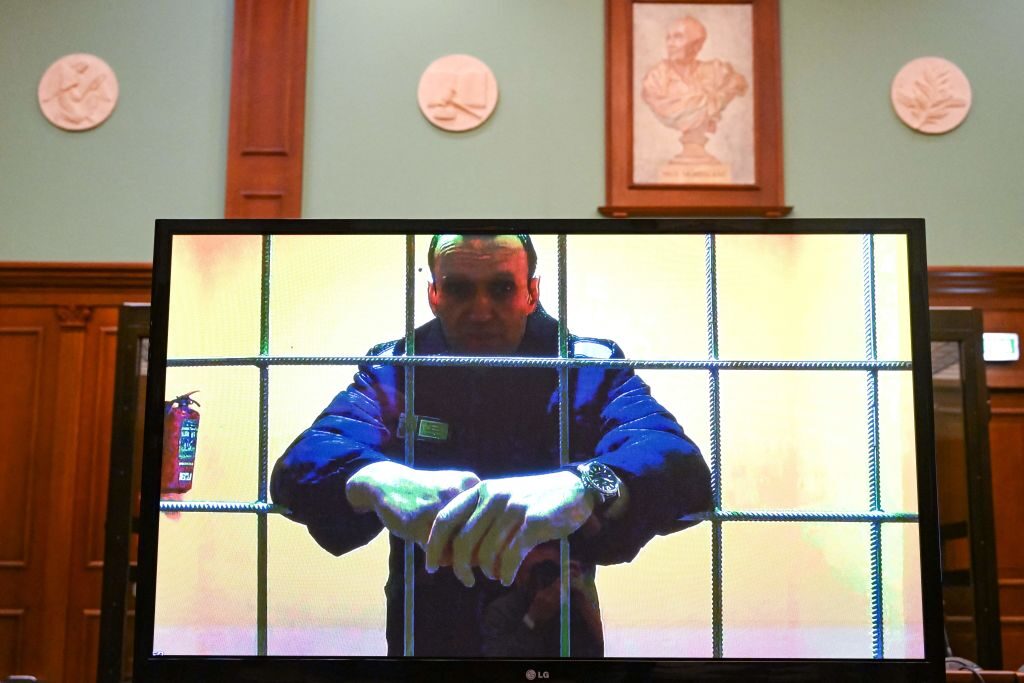

File/Opposition leader Alexei Navalny appears on a screen set up at a courtroom of the Moscow City Court via a video link from his prison colony during a hearing of an appeal against his nine-year prison sentence he was handed in March after being found guilty of embezzlement and contempt of court, in Moscow on May 17, 2022. (KIRILL KUDRYAVTSEV/AFP via Getty Images)

Navalny was able to fill the streets of Russian cities with protesters on several occasions. The protests were broken up with mass arrests, one of which was invariably Alexei Navalny. He joked about his arrests in social media posts and media interviews. He was still cracking wise when he was sent to the Arctic penal colony where he died.

One of Navalny’s first big protest marches was against election fraud in 2011. Even though the vote was heavily rigged to keep Putin in power, Navalny managed to hold United Russia down to less than half the vote. He ran for mayor of Moscow in 2013 and was promptly sentenced to five years in prison for “embezzlement” in a politicized trial.

Navalny and his brother Oleg were accused of embezzling about $500,000 from a state-owned timber company while he was an advisor to the governor of the Kirov region in 2009. When the judge handed down a three-and-a-half-year prison sentence to Oleg, Navalny cried: “Aren’t you ashamed? Why are you jailing him? This is a dirty trick. To punish me more?”

Navalny was released from jail after international denunciations and massive street protests against his arrest and, while he ended up with a strong 27 percent of the vote, it was not enough to force incumbent Moscow mayor Sergei Sobyanin into a runoff election. Navalny’s campaign accuses Sobyanin of rigging the vote to avoid a runoff.

The Putin regime settled for suspending Navalny’s sentence, which allowed him to remain free but effectively barred him from running for office, maintaining a fiction of opposition that Putin’s regime called “managed democracy” or “competition without change.”

Putin would occasionally set up hapless punching-bag opponents to run against him in dubious elections he would “win” by gigantic margins, stuffing the ballot boxes as needed to ensure his margin of victory made headlines, while legally barring genuine opposition leaders like Navalny from contesting his power. When Navalny tried to run for president in 2018, his embezzlement conviction was invoked to disqualify him.

Navalny intensified his anti-corruption activism as head of a non-profit agency called the Anti-Corruption Foundation (its Russian acronym was FBK) he founded in 2011. The FBK’s YouTube videos racked up millions of hits. One of the FBK’s 2017 videos accused sitting Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev of corruption, drawing 7 million views and inspiring tens of thousands of people to march in the streets. Navalny made a point of marching with his supporters and was repeatedly arrested for doing so.

Other members of FBK tried to run for the Moscow city council in 2019 but were banned from the election, prompting more street protests. Navalny developed a strategy called “smart voting” that basically meant “vote for anyone except Putin’s United Russia party.” He used it several times over the years to dent United Russia’s power.

In August 2020, Navalny was flying back to Moscow after working with activists in Siberia when he became mysteriously ill, sweating profusely and losing consciousness. Navalny’s team immediately suspected he had been poisoned. His plane made an emergency landing in Siberia, where Navalny spent some time hospitalized and breathing through a ventilator.

File/Police detain Alexei Navalny, a prominent anti-corruption whistle blower and blogger during protests in Moscow, late Tuesday, May 8, 2012 a day after Putin’s inauguration. (AP Photo/Sergey Ponomarev, File)

Navalny’s friends and family insisted he was not safe in Russia, especially after Siberian doctors blithely insisted they could find no trace of toxins in his system. He was transferred to a German hospital, whose doctors quickly determined he had been poisoned with a lethal nerve agent called Novichok, the same poison Russia used on former spy Sergei Skripal and his daughter in the United Kingdom in 2018.

Navalny survived and in December 2020 he claimed he was able to trick an agent of Russia’s FSB security service into admitting he was part of the unit assigned to shadow Navalny during his trip to Siberia and put Novichok in his underwear.

Navalny returned to Moscow from Germany in January 2021, fully aware he would be arrested upon arrival. The Russian government charged him with violating his probation from the 2013 embezzlement case and took him into custody at Sheremetyevo airport in Moscow. He was held in extended “pretrial detention” and sentenced to two-and-a-half years in prison for violating his parole in February 2021.

While imprisoned in January, Navlany’s investigative team released its most provocative corruption report to date, a video expose of the lavish “billion-dollar Putin palace” constructed in southern Russia, allegedly by oligarchs who wanted to demonstrate their fealty to the authoritarian ruler. The palace was the size of a small city and included amenities to indulge all of Putin’s expensive hobbies including wine-making, ice-skating, tennis, and cinema. It even boasted a nightclub with a stripper pole, which Navalny sarcastically suggested might have been a “training ground for firefighters.”

“Putin’s friends, who received from him the right to steal whatever they wanted in Russia, thanked him a lot. But they also chipped in, collected 100 billion rubles and built a palace for their boss with this money,” Navalny said.

“They will keep on stealing more and more, until they bankrupt the entire country. Russia sells huge amounts of oil, gas, metals, fertilizer and timber, but people’s incomes keep falling and falling, because Putin has his palace,” he warned.

The Putin regime was infuriated by the expose, bouncing Navalny into increasingly harsh prisons and heaping more charges and sentences on him. The NBK and other groups linked to Navalny were outlawed as an “extremist” organization and their offices across Russia were shuttered in June 2021. Navalny’s allies later relaunched the NBK as an international organization with American and European members.

When he was sentenced to nine more years in prison for embezzlement in March 2022, Navalny quoted from the American television show The Wire: “You only do two days. That’s the day you go in and the day you come out.”

“I even had a T-shirt with this slogan, but the prison authorities confiscated it, considering the print extremist,” he added.

Navalny disappeared for most of December 2023, to the great alarm of his friends and allies. He reappeared in the Arctic prison camp known as Polar Wolf near the end of the month, having been transferred in secret.

In January 2023, hundreds of Russian doctors signed a letter to Putin asking him to “stop abusing” Navalny, whose health was deteriorating in prison.

File/Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny appears on a video link from prison provided by the Russian Federal Penitentiary Service at Moscow City Court, Tuesday, May 24, 2022. (AP Photo/Alexander Zemlianichenko)

“It is almost impossible to get to this colony; it is almost impossible to even send letters there. This is the highest possible level of isolation from the world,” said Navalny’s chief strategist Leonid Volkov. When he regained access to social media, Navalny made jokes about getting frostbite and taking over as Father Frost, Russia’s grim version of Santa Claus.

“The detention conditions and the appearance of Aleksei Navalny make us greatly concerned for his life and health. From the medical point of view it is clear that Aleksei is not receiving sufficient medical help,” the doctors said, signing the letter with their full names in an extremely rare example of public criticism directed at Putin.

This pleading fell on deaf ears, and Navalny reportedly died in the Polar Wolf camp on Friday, supposedly collapsing soon after he complained of feeling unwell after an exercise walk. The prison claimed its medical team tried to resuscitate him and failed. Navalny was seen in good health, and in good cheer, in a video of his court appearance on Thursday.

Putin did not comment on Navalny’s passing, but the Kremlin said he was informed while traveling through the Urals to visit factories. Navalny’s wife Yulia said she was not sure he was really dead, because “Putin and his government lie incessantly.”

COMMENTS

Please let us know if you're having issues with commenting.